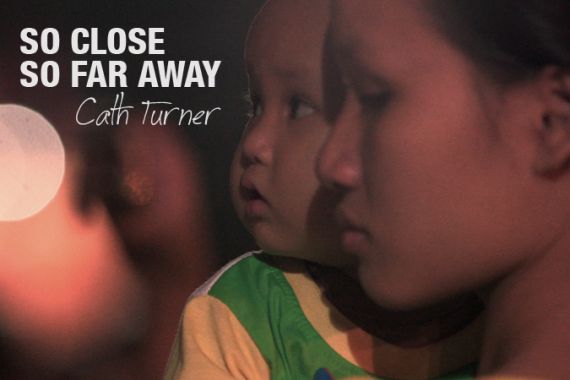

So Close So Far Away

Cath Turner examines the consequences of ‘Operation Babylift’ at the end of the Vietnam war.

‘Operation Babylift’ was one of the defining events of the Vietnam War and its legacy will continue for many years. The world is unlikely to ever see anything like it again.

It was at the end of the war in 1975, when under ‘Operation Babylift’ thousands of Vietnamese children were removed from the country and put up for adoption across the Western world.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRwanda genocide: ‘Frozen faces still haunt’ photojournalist, 30 years on

Underground tunnels found in Israel from Jewish revolt against Romans

Lost in Orientalism: Arab Christians and the war in Gaza

Al Jazeera’s Cath Turner was one of those children – an Asian child growing up in white Australia.

In this episode of Al Jazeera Correspondent, Cath returns to her native and adopted homeland to explore the psychological effects of transnational adoption on these Vietnamese babies.

Taken from their homeland they became a very small minority in their adopted countries in a very obvious way.

CORRESPONDENT’S VIEW

By Cath Turner

I have always known I had an unusual start to life. But like everyone else, I have no memory of my first few years.

I do not remember anything about Vietnam. So I have always felt a bit detached from that part of my life. I have always talked about it like it was my cousin’s experience or someone I vaguely know.

When I pitched my story for the Al Jazeera Correspondent series, it was from a reporter’s point of view. I wanted to draw attention to the short and long-term effects of adoption; of what happens when a child is moved to a foreign country and placed with a family that looks completely different.

I wanted to talk about identity, belonging, racism and multiculturalism.

It seemed like a story that people around the world would relate to, and Al Jazeera the perfect place to tell it. My editors agreed.

But as we got closer to the first day of filming, I started to realise how personal it was going to be.

Al Jazeera’s viewers know me as New York correspondent. I am comfortable looking into the lens of a camera and talking about the United Nations, the New York Stock Exchange, the latest technology news or the economy.

But that does not mean you know anything about my family, my childhood or where I grew up.

This documentary was going to change all that. I was going to lay myself bare in front of the camera, relive some of the most difficult moments of my life and open myself up to judgement.

But I also came to realise that it would be a journey of self-discovery and reflection; of resilience and success. And so I forged ahead, knowing that I am – and have always been – surrounded by an abundance of love and support.

It has been a very cathartic experience.

Ever since I found my birth mother in 2003, I have been constantly juggling two families.

Most people assume my Vietnamese family was the perfect end to a fairytale – and in many ways it has been. I have been able to answer many questions that have plagued me my whole life – about my birth father, my DNA, my heritage.

But it has also come with some difficulties.

I grew up with my Australian family and identify most strongly with them. But I now have a Vietnamese family who wants to connect with me and would love nothing more than for me to move back to Ho Chi Minh City and start a family.

I always try to make sure no one in either family feels neglected, abandoned or unloved. And I know I am very lucky to have two families who accept, respect and genuinely like each other.

But this documentary is about much more than just me. I am only one tiny piece of ‘Operation Babylift’. My producer, cameraman and I met many people who have been directly and indirectly affected by it. And we barely scratched the surface.

The more people we spoke to, the more we realised how multi-layered, how widespread and how devastating the effects of ‘Operation Babylift’ really are.

And for the vast majority of them, there is no resolution or closure in sight. Scarce records and paperwork combined with the fog of war make it next to impossible to find the answers so many are looking for.

Thousands of Vietnamese children were removed from their homeland and have no way of tracing their bloodline or finding out their true identity. Some do not want to know; others are desperate to fill in the blanks.

Thousands of Vietnamese parents have no idea what happened to their sons and daughters, given up to the ‘Babylift’. They may never know. They can only hope their child is still alive and happy. And dream of a reunion.

The story of ‘Operation Babylift’ has been told many times over the last 37 years. And I believe it will continue to be told, as the repercussions of such a dramatic event continue to ripple through generations to come.