Net Losses: Searching for the Soul of British Football

What has happened to the beauty of the beautiful game? Andrew Richardson goes in search of the soul of British football.

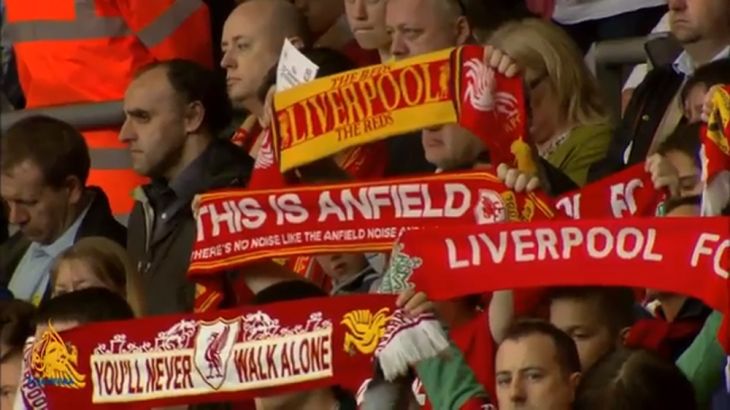

English football clubs were once at the centre of their communities, but that spirit is eroding in Britain’s top flight football. Liverpool FC’s anthem is You’ll Never Walk Alone – but has this franchise left their fans behind?

A generation who grew up watching football in the 1970s and 1980s now feels alienated by the clubs they followed as children. The instinctive connection between the terraces and the players has gone. A football ground used to be the centre of a community. Now it is just another out-of-town shopping mall.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBellingham’s late El Clasico winner leaves Madrid with one hand on La Liga

Man Utd win FA Cup semifinal thriller against Coventry on penalties

Manchester City vs Chelsea 1-0: FA Cup semifinal – as it happened

The Premier League is the self-styled “biggest league in the world”, but most top clubs are in debt, over-charging their fans for tickets and hoping for a Gulf petro-dollar bail-out. While the Premier League becomes a play thing for foreign owners and tourists, football is re-emerging elsewhere.

Many fans who grew up supporting Manchester United or Liverpool are taking their own kids to watch lower league football where they can feel they are part of the team.

What has happened to the beauty of the beautiful game in Britain? Al Jazeera’s Andrew Richardson goes in search of the soul of British football.

CORRESPONDENT’S VIEW: SEARCHING FOR THE SOUL OF BRITISH FOOTBALL

By Andrew Richardson

Little has changed around Liverpool’s Anfield Stadium in my lifetime. It remains a resolutely working class area. Many nearby houses are still derelict. The chip shop still provides the pre-match meal of choice. The local kids still want a pound to ‘mind your car’ while you are at the game.

But that game we all go to watch has changed beyond recognition. More than 100 years ago, the football team that I grew up supporting was founded over a drink in the back room of a local pub. More recently, the ownership of that same club has been fought over for hundreds of millions of dollars.

This once most localised of sporting rituals now attracts a global audience. The English Premier League is a stage for many of the world’s best players; it attracts billions of dollars of revenue and hundreds of millions of worldwide viewers. But the fans closest to home are not quite so sure where they stand in this new global order.

|

|

Huge television deals are made, player wage packets continue to fatten and yet financial black holes seem to be everywhere.

Ticket prices at most turnstiles continue to race ahead of inflation. Club debts in the Premier League are in the billions of dollars. Many fans spend as much time contemplating their side’s financial future as they do its footballing one. And many supporters feel increasingly disconnected from a game they used to believe was theirs.

Just down the road from Anfield is the rather more humble home of AFC Liverpool. A team set up in 2008 by a few hundred supporters who felt they had been priced out of the Premier League. The side play on a shared pitch and in a local league but the standard of football is not really what this venture is about. It is instead about providing an affordable match day experience.

“Paying 50 quid for a ticket to go and watch Liverpool play just isn’t very family friendly. That’s not the fault of a particular club, it’s just the way football has gone,” explains Chris Stirrup, the chairman of AFC Liverpool.

“When I was growing up, you’d wake up on a Saturday morning and go to the match. Now for a lot of children and families as well Saturday football involves Sky Sports, watching the goals go in on the telly. We’re not a protest against Liverpool. Everyone here is a Liverpudlian, we still go and watch Liverpool games when we can, it’s just that for whatever reason we are not able to get into Anfield anymore.”

AFC Liverpool are just one of a number of similar sides that have been formed across the country. The crowd was not larger than 200 or 300 in number on the day I went, but that it was there at all was revealing. These fans have been exiled in their own cities, by their own clubs and their own national game.

Historically, football was all about the working man. In England’s industrial centres, the game offered some much needed and very affordable escapism. Matches kicked off on a Saturday afternoon to coincide with the end of the working week. Those days are long gone. Ticket prices no longer reflect the fans’ needs but the need for a club to make money. Kick-off times reflect not the working week, but a television schedule.

Jay Mckenna is just one lifelong supporter who feels the Liverpool faithful are being taken for granted.

“Football supporters are treated as a commodity. It’s expected that if I don’t turn up, someone else will take my place. Or that if I don’t want to spend 50 pounds on a football shirt, someone else will. That’s not a nice attitude to have. The powers that be, the Football Association, the Premier League and the football clubs need to realise the importance of supporters. They need to realise that without us they wouldn’t exist, without us they wouldn’t be able to attract these multi-million pound sponsorship deals,” Mckenna says.

Buying into a brand

Perhaps the most disorientating aspect of the modern game is the way clubs are bought and sold. These institutions that are so central to all our lives and which our families have been following for generations are now being treated just like any other commercial product. Fans at Chelsea or Manchester City may be enjoying the cash drenched extravagances of their new owners but other supporters have seen their clubs plunged into financial crisis.

“Some of this ownership stuff just looks odd,” says Rogan Taylor, a Liverpool fan who has spent much of his professional life as a university academic researching his sporting passion.

“The access is so unregulated. These aren’t yoghurt factories or supermarkets, they’re football clubs. If you have a few quid and want a football club it seems to be a case of go ahead, help yourself, lad.”

Like any top club Liverpool are now a brand. Foreign markets have to be exploited to generate the millions needed to stay competitive on the pitch. Supporters understand this. But they also know they are part of the product that is sold to the world. How they continue to relate to their club is a question all fans all are now having to contend with.

|

|

Net Losses aims to get an understanding of the concerns supporters have at all levels of the game, not just in the Premier League. We contrast the English experience with that of Germany, where fans have a big say in how their clubs are run. We will also look at the new rules which may produce a saner financial future across the European game.

There is no question that the league we get to watch is quite something. It is a stage for some of football’s greatest players and rivalries. There is huge pride that it is English football the world seems to want to watch. It is true also that English fan culture is every bit as marketable as the teams.

Will that global audience still be as interested if one day their television backdrop reveals empty seats rather than the impassioned masses of old? Supporters are entwined in the folklore of this game. But should that relationship between the people and their club ever unravel the first link in a supporter chain that stretches across the globe will be broken and the game as we all know it could be lost forever.