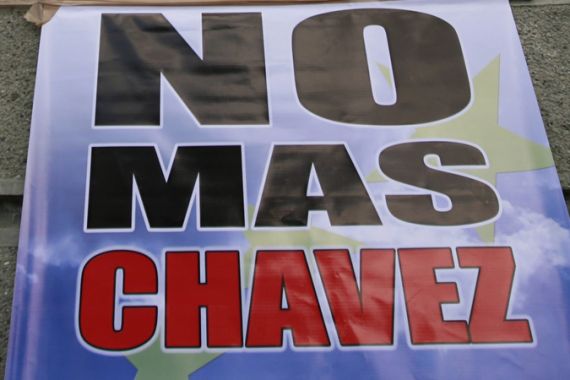

From saviour to dictator?

To some Hugo Chavez is a hero, to others he poses a threat to the cherished democracy they will fight to defend.

|

| As some celebrated 200 years of independence, others mourned what they see as the erosion of the rights they secured 200 years before [EPA] |

When he took office in 1999, Hugo Chavez, the Venezuelan president, was widely embraced. But with the passage of time, some Venezuelans have grown disillusioned, believing that their president poses a threat to freedom and democracy.

In a country divided between those for whom Chavez is a saviour and those who consider him a dictator, one man has been prepared to put his life on the line.

Here Luis Del Valle, the director of Challenging Chavez, explains how students have become a major force of opposition in Venezuela.

| DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT: LUIS DEL VALLE |

“What is the purpose of your visit?” asked the customs officer when I arrived at Caracas airport, in the Venezuelan capital. I responded, as it had been suggested I should, by saying: “I’m coming to film the celebrations for the 200-year [anniversary of] independence.”

“Why instead you don’t film the misery we live in?” came the unexpected reply as the officer stamped my passport.

Just a little later as I sat in the car and listened to the Chavez-supporting driver tell me all about subsidised food and cheap loans, I was able to see just how polarised Venezuela is.

The student organisation we were there to film comes down very firmly on one side of that divide.

The students there are very critical of the government and refuse to acknowledge any good it may have done. They do not believe that the social programmes have benefited the poor and are convinced that corruption is widespread among officials.

For them Venezuela is living under an authoritarian regime where freedom of speech has been restricted and democracy is at peril. To fight for freedom is what drives them and, in such circumstances, objectivity is sometimes very difficult to achieve.

Broken dreams

|

| Villca, right, and 20 other students go on hunger strike to protest against the Chavez government [EPA] |

Villca Fernandez – the main character in the film – is one of the best representatives of the fight students have fought in recent years. He has taken part in street protests, marches and hunger strikes and has even sewn his lips together in a bid to generate attention for the issues he seeks to challenge.

His commitment towards defending democracy and freedom is impressive and does not seem to fade, despite the bullets and punches he has endured and the threats he and his family have received.

I cannot recall meeting anybody with such strength. This is a guy with determination but also a huge amount of charisma; someone who has time to listen to others and to help them whatever their needs might be.

However, this is also somebody whose activism has overshadowed his more youthful dreams of becoming a footballer or travelling the world. It was not easy to chip away at the image of strength Villca sought to portray in front of the camera to get him to openly talk about those broken dreams.

As always, things did not go as planned. Initially, the students had decided to protest at a regional summit that was due to be held on a Venezuelan island. But that meeting was cancelled because of Hugo Chavez’ illness. So the students changed plans and decided to travel to Caracas to attend the celebrations for the 200th anniversary of the country’s independence.

They wanted to be there to tell the country it was losing its freedom and to generate some media attention. But the trip was not without its problems. The students had to travel for 15 hours to reach the capital so finding food and a place to sleep was difficult. Plus, with their university semester coming to an end, many were busy with exams and nobody knew how many would be able to attend.

‘The revolution has its own guards’

Some students from other parts of the country joined the main group in Caracas, but there were fewer than 100 people in total. Having seen other marches with thousands of students in attendance, the turnout for this one was a little disappointing. But, despite the low number, spirits were high and the students managed to carry out their first day of protests without any trouble.

I was impressed by the organisation and discipline they showed, always paying attention to their leaders and obeying their instructions. It was also impressive to see their determination once they found out about the detention of a student from the capital who was not taking part in the protests. Very quickly they went to the police station where he was being detained to show their solidarity.

It was while filming there that we noticed civil police agents taking photographs of us. Having filmed in Venezuela before with members of the opposition, this was something we knew might happen. What we did not expect was that later that night a pro-government TV programme would send us their “regards” and advise us to take care, whilst emphasising that the revolution has its own guards who will do anything to defend it.

In the end I think the main regret I have is not being able to follow some of the students who support the current regime. Despite the questions we asked Villca and other members of the movement about positive things the government may have done, I believe this film will be disliked by “Chavistas”. But this is Venezuela and a film about Villca and the student movement will automatically be rejected by half the population before they have even watched it.