It’s time for the African Union to put a stop to ‘third-termism’

The AU needs to take action against the Guinean president’s attempt to change the constitution and extend his rule.

Two issues have dominated the attention of the African Union (AU) in the last weeks: the upheaval in Sudan and the launch of the African Continental Free Trade Area. In the midst of these, a brewing crisis in Guinea seems to have skipped attention.

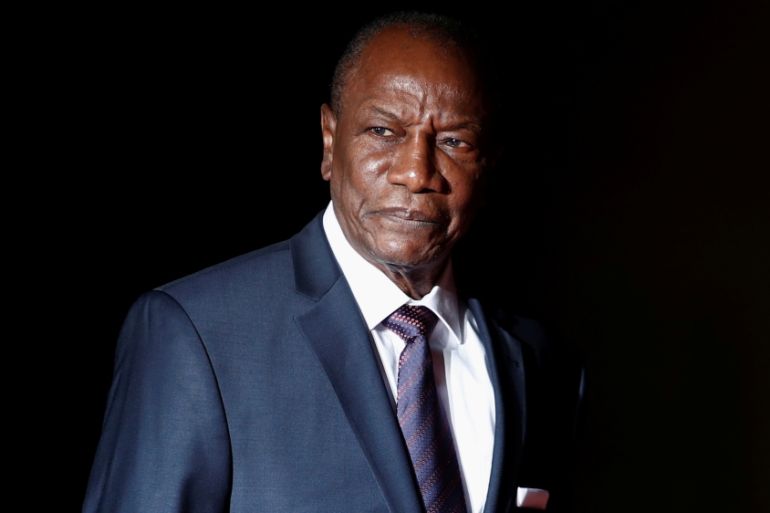

Guinean President Alpha Conde, the West African country’s first democratically elected leader, who is currently serving his second five-year term, is supposed to leave office in 2020 under the rules of the 2010 Constitution. However, the 81-year-old is thought to be seeking ways to orchestrate a constitutional change that would allow him to run for a third and even a fourth time.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIt is time for a new Africa beyond borders and boundaries

Addis summit raises questions about AU’s muted stance on Ethiopia rifts

It is high time the AU takes a firm stance against Ethiopia’s aggressions

Conde has so far evaded talking directly about the issue, but he has also refused to rule out a third term, saying his decision would be based on the “will of the people”. Prime Minister Ibrahima Kassory Fofana, appointed in May 2019, also signalled that a referendum on a new constitution is a possibility. A billboard containing the message “Yes to a referendum. Yes to a new Constitution. We support you for life.” has also been hoisted outside Guinea’s National Assembly.

If the president succeeds, he will be following in the footsteps of his predecessor, Lansana Conte – a man Conde fought hard and long to depose – who abolished term and age limits on the presidency in 2001 and died in office in 2008.

Conde’s apparent third-term bid is already causing significant deterioration of stability in Guinea. Opposition parties, civil society groups and trade unions opposed to constitutional reforms have established the National Front for the Defense of the Constitution (FNDC) and called for protests. Security forces have wounded and arrested protesters and one person has reportedly been killed.

Guinea is not the only country in Africa that is grappling with the problem, dubbed “third-termism”, where incumbents either eliminate or modify presidential term limits to cling on to power. Many countries, from Egypt to Uganda to Comoros are facing the very same problem today.

The AU has controversially avoided engaging the third-term phenomenon in the past, drawing criticism that the organisation is a mere “Big Boys’ Club” serving the interests of incumbents. Conde’s attempt to cling on to power presents the AU with a prime opportunity to redeem itself, deter “constitutional coups” and support democratic alternation of power.

The AU’s silence on third-termism

The AU regime against the unconstitutional change of government, first pronounced in the Lome Declaration, formalised in the AU Constitutive Act and further elaborated in the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, encompasses a range of different acts, and tasks the institution with countering coups and other types of unlawful and undemocratic power grabs.

In line with these provisions, the AU has consistently rejected military coups, most recently taking a strong stance against the attempt of the Sudanese military to take over the country following the removal of long-time President Omar al-Bashir. Moreover, on two occasions, the AU has rejected the refusal of incumbents to step down following electoral defeat – in Ivory Coast in 2011 and in the Gambia in 2017.

The African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance also prohibits any amendment or revision of the constitution or legal instruments that constitute “an infringement on the principles of democratic change of government”. However, the AU has never publicly invoked this prohibition, despite the prevalence of third-termism across the continent and has largely remained silent in the face of “constitutional coups” – incumbent leaders making amendments to the constitution to avoid term and age limits.

While it generally calls on states to follow established procedures for constitutional amendment and to ensure full citizen participation in the process, the AU seems to have merely opted to engage in quiet diplomacy on the issue. Talks of amending the Democracy Charter to prohibit the third-term phenomenon have made little progress. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS ), which Guinea is a member of, came closest to prohibiting third terms in 2015, but its efforts were scuttled by The Gambia and Togo.

Most recently, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt, the current chair of the AU Assembly, led the adoption of a constitutional amendment through a referendum in April 2019, paving the way for him to run again.

Also in 2019, the Ugandan Supreme Court upheld a constitutional amendment removing age limits on the presidency allowing the ageing President Yoweri Museveni to extend his more-than-three-decade reign. The age limit was the last remaining hurdle after Museveni orchestrated the removal of presidential term limits in 2005.

In July 2018, President Azali Assouman of Comoros dissolved the Constitutional Court and Parliament and organised a referendum extending term limits and the inter-island rotational presidency. In March 2019, he ran and won another term in an election that the AU has refused to endorse.

As with similar changes in the past years, the AU did not reject or otherwise condemn these constitutional changes in these countries. In fact, the AU sent observers to the March 2019 elections in Comoros that the constitutional change necessitated – a decision that South Africa‘s former President Thabo Mbeki has recently criticised.

The closest the AU has come to rejecting term extension was in 2015 when President Pierre Nkurinziza of Burundi secured a constitutional interpretation by the Constitutional Court to run for a third term, after his proposed constitutional amendment to allow a third term was defeated in the Senate. Nevertheless, the AU’s initial opposition was not done within the framework of unconstitutional change of government and Burundi never faced any serious consequences.

In short, the AU repeatedly took action to counter unconstitutional change of power, while turning a blind eye to leaders altering the constitution to retain power, fuelling accusations of favouring incumbents.

The reluctance of the AU to intervene in these cases may partly because the changes ostensibly followed prescribed constitutional procedures for reform, in some instances with popular approval, as was the case in Egypt.

Guinea’s unique circumstances

The current situation in Guinea, however, is unlike Egypt or Uganda for an important reason – the 2010 Constitution clearly prohibits the amendment of the provision limiting each president’s mandate to two five-year terms. Article 154 of the constitution unequivocally declares that “the number and the duration of the mandates of the President of the Republic may not be made the object of a revision”.

This is not lost on Conde. Instead, he and his supporters are relying on clever interpretative gymnastics that makes a conceptual distinction between the making of a “new” constitution and the “revision” of the existing one. While there is indeed an academic distinction between these two acts, in this case, the AU must call a spade a spade: an effort to undermine constitutionalism and consolidate incumbency.

Conde’s supporters seem to be drawing from a similar playbook that allowed President Denis Sassou Nguesso of the Republic of the Congo to justify the extension of his term. In 2015, Nguesso bypassed the explicit constitutional provision banning amendments that tamper with the presidential term limit through the adoption of an ostensibly “new” constitution that established a new three-term limit. The AU lost a golden opportunity to enforce its norm back then, and Nguesso is still in power.

Nevertheless, this distinction clearly runs contrary to the constitutional spirit, if not its letter. The AU must therefore call this constitutional trickery what it is: a reform initiative that infringes on “the principles of democratic change of government” and that is contrary to the established norms of constitutional change of government.

Conde’s plan to adopt a new constitution is a pretext to operate outside of any constitutional or other limits, therefore undermining constitutionalism. The AU should therefore draw the line and make it clear that the planned manoeuvre contradicts the AU’s established rules against the unconstitutional change of government in Africa and will not therefore be acceptable.

In line with principles of subsidiarity, ECOWAS should also draw on continental normative frameworks to lean on Conde to drop any plans to run again.

A rejection of Conde’s plans would redeem the AU from its abysmal record of standing on the sidelines as incumbents trample over principles of democratic alternation of power and constitutionalism. It will also ensure that the unstable situation in Guinea does not deteriorate further. Moreover, such decision would serve the will of the Guinean people, already emphatically expressed in the 2010 Constitution, rather than Conde’s attempt to manufacture a new “popular will” to justify his ambitions.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.