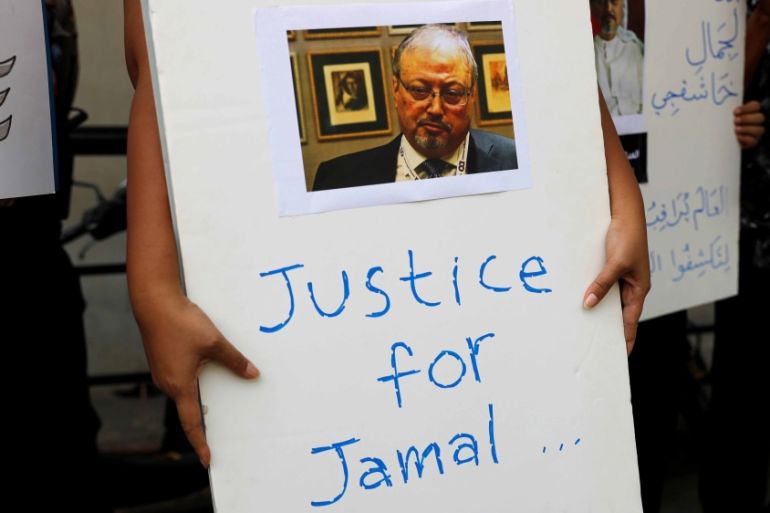

Mark the Khashoggi anniversary by freeing jailed activists

The admission of guilt by the Saudi authorities needs to be accompanied by the release of political prisoners.

A year ago today, I spoke on the phone to Hatice Cengiz, who introduced herself, with a trembling voice, as the fiancé of my friend Jamal Khashoggi. She was standing outside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, extremely concerned that he had not emerged since he entered two hours earlier.

I urged her not to leave until Turkish police arrived, and hastily moved to alert anyone I thought could help. My worst fear was that Saudi officials would try to kidnap Jamal and take him back to Saudi Arabia – he had told me they were trying both to woo and coerce him into returning from his self-imposed exile.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMacron defies criticism to host Saudi Crown Prince MBS in Paris

Saudi Arabia, Greece to sign energy deal, Crown Prince MBS says

UAE arrests Khashoggi’s US lawyer on money laundering charges

When I first urged Jamal to leave Saudi Arabia in January 2017, soon after the government had suspended him from writing and tweeting, my concern was that the new crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, would jail him or ban him from travelling. For years, I had seen cases like his all over the Middle East. At first Jamal resisted, relying on assurances from Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal and Prince Turki al-Faisal, two senior royals who had been his close friends for decades, that all would be fine and “things would calm down”. The prospect of leaving his grandchildren behind especially pained him.

By the summer of 2017, Jamal had decided he would leave, unable to tolerate his intellectual confinement, and convinced that he could be next in line for arrest. Indeed, soon after his arrival in the US, the arrests dramatically escalated, with a large number of writers, scholars and journalists put behind bars.

By November, Prince Al-Waleed was also imprisoned in the luxurious confines of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in Riyadh along with other royals, government officials, business leaders and media figures. The bulk of the prince’s assets, along with the assets of many others, were confiscated in what would come to be known as one of the greatest shakedowns in recent history, with the state claiming it had “recovered” $107bn with nary a judge or lawyer involved.

No one – certainly no Saudis – I talked to had expected these mass arrests of prominent figures, any more than they expected the crude catch-and-release of Lebanon’s prime minister, Saad Hariri, that Autumn.

But no shock was greater than the murder a year later of Jamal Khashoggi in the Istanbul consulate, not only for its gruesomeness but also its epic bungling: from the hard-to-miss arrival of the Saudi henchmen, accompanied by a bone-saw wielding forensic pathologist and a Jamal body-double, to the mysterious malfunctioning of consulate video cameras and surprise leave for consulate staff.

The drip, drip, drip of revelations by the Turkish government, along with the daily unravelling of Riyadh’s lies, ultimately forced a confession that Saudi government agents had killed Jamal. Shifting its narrative from an unplanned fistfight gone wrong to a premeditated but rogue operation by low-level officials, Saudi Arabia is now prosecuting 11 officials in a face-saving secret trial. The government never charged the reported mastermind of the execution, Saud al-Qahtani, the crown prince’s chief adviser.

The Saudi government grossly miscalculated the global consequences, particularly for the crown prince, of such a crime being exposed. It may not yet have resulted in criminal liability, but it has certainly produced massive reputational, political, and economic costs to him and his government, including hundreds of millions in Saudi public money spent on lobbyists to bolster his global image.

The CIA’s conveniently leaked findings, based on its own independent intelligence, that the crown prince ordered the murder made it even harder to brush away the damage. While sanctions by the US, UK, Canada, Germany and many other states against implicated Saudi officials have excluded the crown prince, and businesses that initially recoiled are worming their way back to profit-making in the kingdom, the toll remains immense.

Indeed, the murder made possible the impossible – solid bipartisan action in a deeply divided Congress, which passed three bills to suspend arms sales to Saudi Arabia for its war crimes in Yemen (all vetoed by President Donald Trump, alas). In July, the House of Representatives passed a bill, conditioning the approval of defence spending on the release of a report on Jamal’s murder.

In November 2018, the crown prince also faced the threat of an investigation for torture and extrajudicial killing, supported by my organisation, Human Rights Watch, when he turned up for the G20 in Argentina. Since last year, he has not dared to show his face in the US or Europe, where he will likely face more lawsuits.

Meanwhile, prominent celebrities, like Nicki Minaj, have cancelled appearances in Saudi Arabia, and just last month, the New York Public Library pulled out of an event organised by the Crown Prince’s MiSK Foundation, following public outrage.

Last week the crown prince made an admission of responsibility during an interview for CBS’s 60 Minutes programme in the genre of “the buck stops here because it happened under my watch”, which may be an effort to mitigate the damage to the kingdom. It is certainly in line with international law, which holds a state responsible for the unlawful acts of its agents acting in their official capacity – in this case, the deliberate, premeditated and extrajudicial execution of a government critic.

Whether or not you believe the crown prince specifically ordered the murder, he, as the official in charge of the murderous agents, is responsible. Under international law, the Saudi government is obligated to do three things which are detailed in the UN report of the special rapporteur for extrajudicial executions, Agnes Callamard: provide accountability, offer a remedy, and ensure that it won’t repeat its crimes.

For international crimes such as torture, commanders, up to the highest level, can be held liable for violations committed by their subordinates under the principle of command responsibility.

Accountability means an independent, impartial and public investigation of all those implicated in the murder to uncover exactly what happened – which the Saudi government has promised but failed to deliver – including finally telling us where it has hidden Jamal’s body so that his family can give him a proper burial.

Callamard called for a UN criminal investigation, particularly in light of Saudi Arabia’s non-cooperation with her investigation. Will the Saudi government now cooperate, given the crown prince’s admission, allowing access to evidence and relevant persons in the kingdom? While criminal accountability for all of the guilty may remain elusive, a real investigation would serve the equally important function of telling the truth and establishing the record.

The Saudi government should also remedy those injured by its crime, by apologising to Jamal’s family, friends, and associates, so deeply wounded by this attack on a journalist, and to the US and Turkish governments, for murdering a US resident on Turkish soil.

It must offer compensation to those harmed, not in the form of secretive payoffs in exchange for familial silence, but in the form of an admission of wrongdoing.

The Saudi government needs to prove to its citizens and the international community that it will not continue to silence free expression. Its record since Jamal’s murder – including the continued detention and prosecution of scores of women’s rights activists, writers and scholars, like Loujain al-Hathloul and Salman al-Awdah to name but two, indicates that it continues to punish critical voices.

To convince anyone otherwise requires the immediate release of these jailed Saudis, whose cause Jamal had taken on as his own. A host of reforms are required to ensure Saudis can speak freely – including revamping intelligence forces that target dissidents, establishing laws that enshrine their rights, a penal code that articulates elements of real crimes, and an independent judiciary. But most urgently, the Saudi authorities should release those now languishing in prison.

Other governments should fulfil their own obligations to hold Saudi Arabia to account by pressing for these changes. And they should honour Jamal’s memory, by creating memorials, events and scholarships in his name. Most importantly, they and we should support his most cherished goal: freedom and democracy for the Arab world. As the people of Sudan, Algeria and Egypt have reminded us this year in their own roar of support, it is a goal shared by millions in the region.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.