BJP’s Gandhi paradox

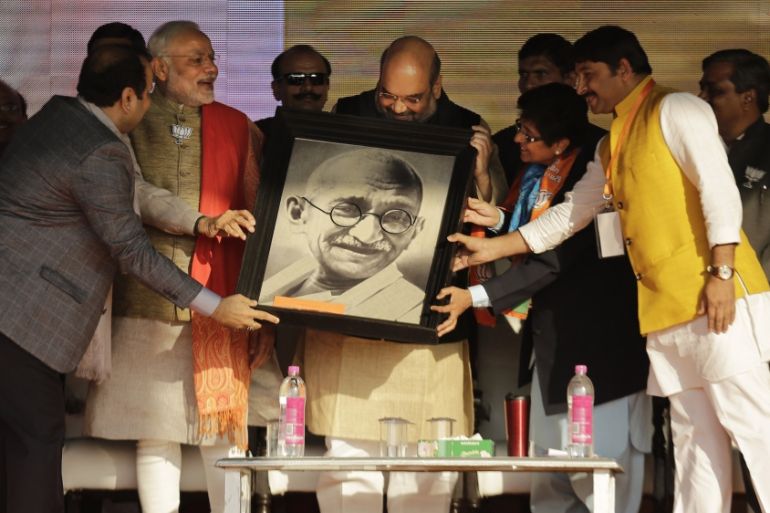

Despite not having a common ideology with Gandhi, the ruling party in India insists on celebrating him.

During the recent “Howdy Modi” rally in Houston, which welcomed Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to the United States, a bald man appeared in the crowd dressed in white, holding a stick and altogether looking like Mahatma Gandhi. In an interview after the event, the man compared the Indian anti-colonial leader to the current Indian prime minister, calling them both “fakirs, saints”.

It was a moment that perfectly illustrated the post-truth era we live in. Today the government of India led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) publicly embraces the towering figure of Gandhi, a man who was deeply committed to the politics of truth and nonviolence and who openly rejected ethnic and religious nationalism and hatred.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIndia: Hindu monk arrested for insulting Gandhi, praising killer

UK considers Gandhi coin to commemorate Indian independence icon

Gandhi’s death anniversary galvanises India’s anti-CAA protesters

It hollows out the core of his teachings and flaunts him as a great Hindu Indian leader, known and celebrated internationally – a grand and worthy figure to whom Modi can be compared.

But uncomfortable facts are easily swept aside in these post-truth times. Since 2014, when Modi’s first term in office started, a large section of the Indian media began to side with the propaganda of power, instead of pursuing the truth for its own sake.This has allowed the party to celebrate Gandhi’s legacy and appropriate his symbolic power.

Doing so is perhaps an attempt to conceal its own politics. After all, you gain moral currency in the eyes of the people when you declare Gandhi to be on your side. It acts as a mark of trust, like Gandhi’s face on the rupee.

Today, as leaders of the BJP and its affiliated organisations attend national celebrations marking the 150th anniversary of his birth, it is crucial to remind ourselves of the premises of Gandhi’s politics.

Gandhi believed deeply in the doctrine of “ahimsa” (compassion and nonaggression). He applied it not only to the anti-colonial struggle he led, but also in his aspirations for relations between the various ethnic and religious groups living within the borders of post-colonial India.

For example, during a 1915 speech at the YMCA auditorium in Madras (today’s Chennai), Gandhi said: “For one who follows the doctrine of ahimsa, there is no room for the enemy […] under this rule there is no room for organised assassination, and there is no room for murders.”

Elsewhere, he went further, declaring: “If I am a follower of ahimsa, I must love my enemy.”

In other words, for Gandhi the enemy did not exist. His mode of politics rejected the invention of an enemy as a tool for political and social control. He applied the same principle to inter-communal relations.

Gandhi believed in democracy and saw the religious “other” as a friend. In his 1909 book Hind Swaraj (Indian Home Rule), he commented on the Hindu-Muslim issue, saying: “There is mutual distrust between the two communities. The Mahomedans, therefore, ask for certain concessions from Lord Morley. Why should the Hindus oppose this? If the Hindus desisted, the English would notice it, the Mahomedans would gradually begin to trust the Hindus, and brotherliness would be the outcome.”

Gandhi’s politics of friendship was premised on pursuing mutual trust between communities and was primarily concerned with solving political disputes. In 1925, he wrote in Young India, the newspaper he published: “I believe in trusting. Trust begets trust. Suspicion is foetid and only stinks. He who trusts has never yet lost in the world. A suspicious man is lost to himself and the world.”

These were not empty words. Gandhi sought to apply his beliefs on the ground, even in his most challenging moments. At the threshold of Independence, when the Congress and the Muslim League pushed their competing political projects, riots erupted in Muslim-majority Noakhali in Bengal, in which some 5,000 Hindus were killed.

The violence posed a major challenge to Gandhi’s politics and he admitted that his “technique of non-violence was on trial”. Still, he decided to go to Noakhali to seek a peaceful resolution. Aware that the Bengal government did little to stop the riots, he nevertheless supported its initiative to form a peace committee.

But while his insistence on nonviolence contributed to the success of the anti-colonial struggle he led, it also earned him many enemies. The RSS, for example, strongly disagreed with Gandhi’s methods and ideology.

In his 1939 book, We or Our Nationhood Defined, one of the leaders of the RSS, MS Golwalkar, rejected the idea of living with difference. He saw all non-Hindus as “traitors and enemies to the National cause.”

Drawing inspiration from the Nazis, Golwalkar wrote: “Germany has also shown how well-nigh impossible it is for races and cultures, having differences going to the root, to be assimilated into one united whole, a good lesson for us in Hindustan to learn and profit by.”

He believed that a nation could only be defined against a racial and religious “other” and promoted the idea of a Hindu-only India. According to Golwalkar, “wrong notions of democracy duped [us] into believing our foes to be our friends.”

Today, it is the ideas of Golwalkar, not Gandhi, that Modi and the BJP espouse.

In its rhetoric and policies, the BJP government has systematically sought to exclude the “other”. Muslim migrants have been called “termites” and critics “anti-nationals”.National registers have been updated to exclude immigrants; cow vigilantism and lynchings have not been discouraged; dissenting journalists, activists and academics have been systematically silenced.

India under the BJP is being made to forget Gandhi’s core teachings. But he is still being used as a symbol for programmes like the “Swachh Bharat” mission which aims to clean up the streets, roads and infrastructure of India’s urban and rural areas. India indeed needs clean toilets, streets and neighbourhoods. But Gandhi in Noakhali, as Manubahen described in her diary, cleared with his own hands, the dung and human excreta thrown into the streets by Muslims opposed to his visit. He cut through social prejudice against manual scavenging in an atmosphere of distrust. Gandhi’s idea of cleanliness included the cleansing of hatred from people’s hearts.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.