Why we should be cautious about the ‘game-changer’ Ebola vaccine

Despite being widely celebrated, the Ebola vaccine might not prove as effective as it is advertised to be.

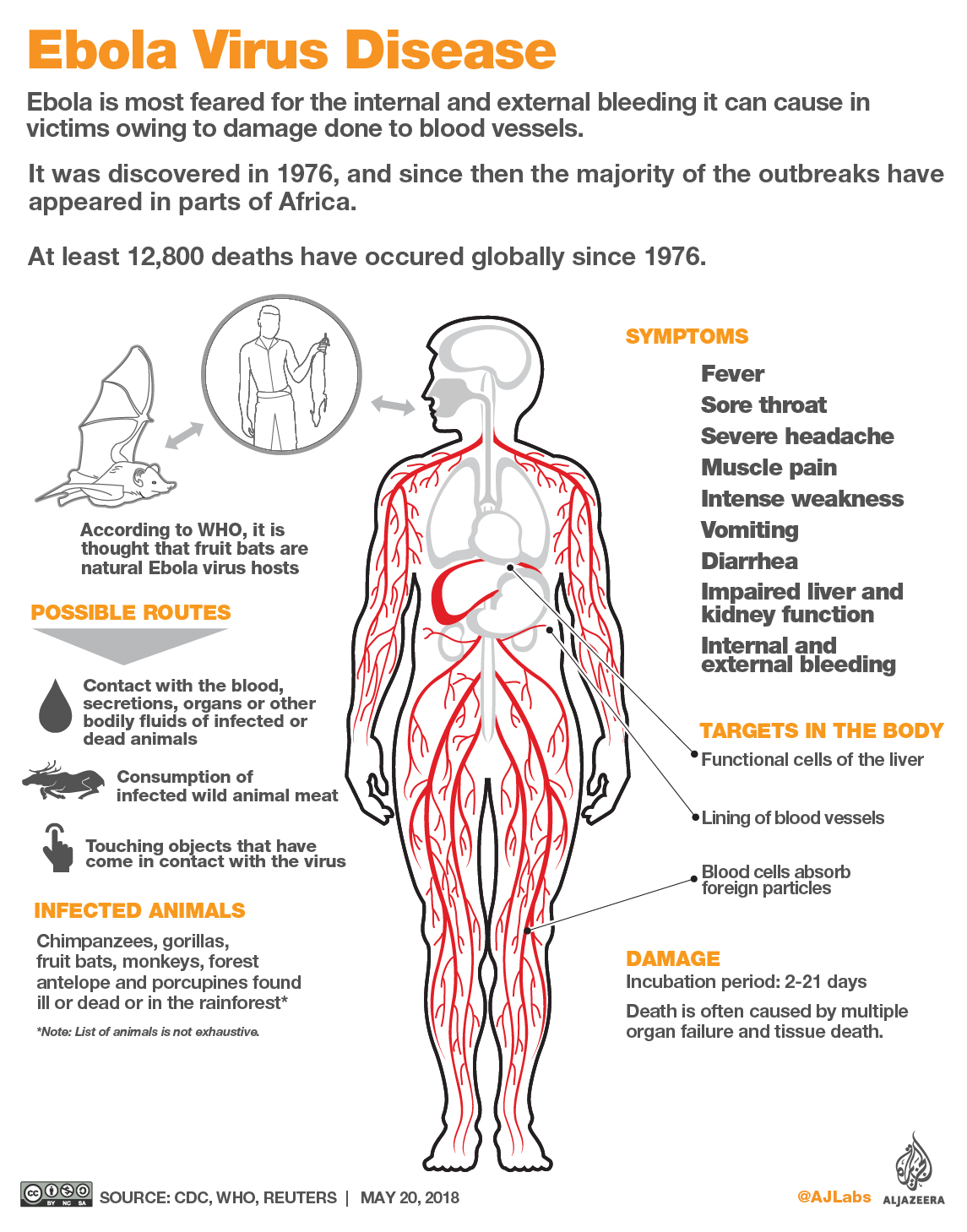

In early May 2018, when the ninth Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo threatened to spread to Mbandaka, a city of 1.2 million people, the global health public relations machine went into overdrive.

Unlike previous outbreaks in the country, or unlike the 2014-16 West African outbreak, international responders quickly announced their support for efforts to contain Ebola. This rapid response by African and Western experts has been heralded as a direct consequence of lessons learned from the West African outbreak, which by 2016 had killed more than 11,000 people, mostly in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsDeadly Sahel heatwave caused by ‘human-induced’ climate change: Study

Woman, seeking loan, wheels corpse into Brazilian bank

UK set to ban tobacco sales for a ‘smoke-free’ generation. Will it work?

By their own report, efforts to assist Ebola response by multilateral agencies like the UN and the African Union have not only been quick, but “impressive”. The World Bank and the World Health Organization have committed $12m and $2m respectively to help the fight against the outbreak. The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, established in 2017, have deployed its emergency response team and committed up to $2m.

Among the highlights of this rapid response is the use of the “investigational” rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine. Beside two vaccines developed and approved by Russia and China, this one has gone the furthest in its development: it has been tested for safety, for its ability to elicit sufficient immune response to fight off Ebola, and for efficacy.

However, the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine, which is currently produced by US-based pharmaceutical giant Merck, is unlicensed by health authorities. It is being administered in the DRC under “compassionate use” protocol, which allows unlicensed, but possibly effective, drugs to be used in the event of an emergency.

The vaccine will be offered through ring vaccination, which means that only close contacts of Ebola patients, contacts of contacts, healthcare workers, and other front-line responders will be vaccinated in the three affected areas of Mbandaka, Bikoro, and Iboko. Experts estimate each “ring” will consist of up to 150 contacts, with an estimated 10,000 who will possibly be vaccinated by the end of June 2018.

Most media coverage about the vaccine’s deployment to the region has been triumphalist, referring to the vaccine as a “game-changer” and “a paradigm shift“. But these reports should be viewed with caution.

During the West African Ebola outbreak, the vaccine underwent phase two and three clinical trials, for safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy. A December 2016 final report by the investigators running the trial in Guinea suggested that the vaccine is 100 percent effective against Ebola.

This figure has been widely reported and continues to be used in reports touting the arrival of the vaccine in the DRC. But there have been reports also questioning the high level of efficacy reported in the trial.

Referring to the Guinea clinical trials, a panel of experts convened by the US National Academy of Medicine, reported the following: “We concur that, taken together, the results suggest that the vaccine most likely provides some protection to recipients – possibly ‘substantial protection,’ as stated in the final report. However, we remain uncertain about the magnitude of its efficacy.”

Further, they expressed some concern that early positive results might make it difficult to justify, on an ethical basis, controlled clinical trials of the vaccine in the future.

It also has to be made clear that people who already carry the virus are likely to develop an infection, even if they receive the vaccine.

Other concerns arise when new pharmaceuticals are tested in settings among vulnerable populations. As noted by Liberian academic Robtel Neajai Pailey, there is a history of medical experimentation among vulnerable populations in the US and parts of Africa.

Informed consent by research participants requires a complex negotiation under any circumstances, but the history of experimentation Pailey and others describe too often intensify community concerns and negative responses to certain medical interventions.

How will the questions about its efficacy be properly explained? Under what conditions can an “Ebola contact” refuse the vaccine? Under what conditions will the vaccine be contraindicated for people who have been close contacts with Ebola sufferers, and how will this be explained?

Recently, I sought personal accounts from clinical trial participants in Sierra Leone, where I work as an anthropologist. During those conversations, I learned second-hand about participants’ inability to report concerning side effects of the vaccine – swollen joints and joint pain; skin lesions; and fever – to the research team.

How will those vaccinated understand their risk of infection and how will this shape their actions if the disease continues to spread? Who among close contacts will be missed through other means, if reports of Congolese communities’ evasion of health workers are true?

In an interview with The Atlantic, Seth Berkley, the director of the NGO Gavi, which has supported the vaccination campaign, expressed concern that people who learn about possible Ebola infections among the vaccinated would lose confidence in the vaccine.

Confidence in the vaccine, however, may very well be the least of the global health community’s problems. If serious, careful efforts to inform communities about the risks and pitfalls and limitations of the vaccine – and knowledge about all of these – are not made, lack of confidence in and mistrust of the health system may be difficult to overcome during future health campaigns like this one.

The introduction of this experimental Ebola vaccine – whatever its efficacy and potential risks – will inevitably shape the landscape of care and communities’ trust of the health system, more generally.

The current narrative has prioritised the vaccine, even as basic public health measures will still be needed to deliver and administer it. Carrying out ring vaccination requires bread-and-butter public health functions: tracing contacts; documenting timing, intensity and location of their exposure to the disease and so on.

The ring vaccination strategy has also caused confusion among the affected communities. In a recent AFP report, MSF officials noted that some people have heard about the vaccine and expect mass immunisation to take place, as is the case with other diseases with which they are familiar. Others allegedly refuse care at the hospital because they are “waiting for the vaccine”.

Although it is not clear how widespread these beliefs are, these allegations suggest that responders are not communicating and receiving “buy-in” for their strategies.

Perhaps health officials have too narrowly focused on the “game changer” potential of the vaccine to a vaguely defined audience in the West, with too little recognition that these triumphalist messages also travel and circulate in the very places where they work.

They starkly contrast with the messages that need to be communicated to the communities facing an imminent threat from Ebola. That is: this vaccine is likely highly effective in the current formulation, but this element is still under investigation; only close contacts will receive the vaccination; and it is possible that some people will fall ill after they have been vaccinated.

But these do not make for catchy, succinct press releases. They do not fit neatly into an outbreak narrative of heroic rescue and scientific progress.

Yet the people of DRC deserve better.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.