Lula: Brazil’s Schrodinger candidate

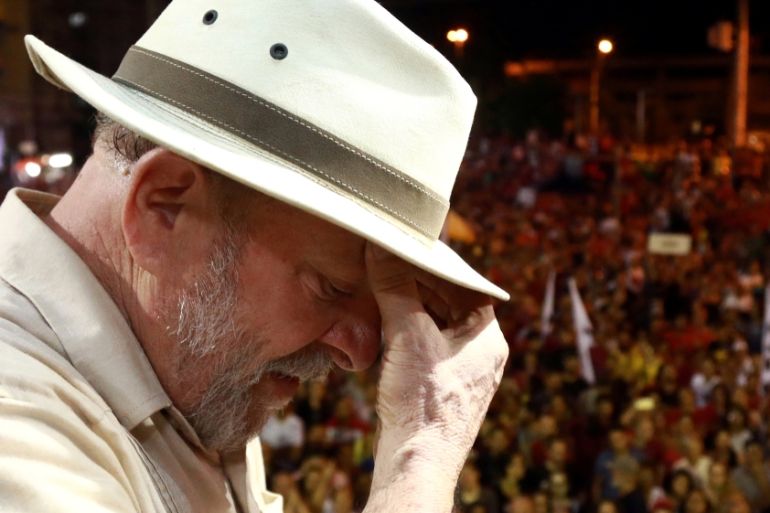

Luis Inacio ‘Lula’ da Silva is currently leading the presidential election polls in Brazil. But he may be jailed soon.

Almost 100 years ago, physicist Erwin Schrodinger proposed a thought experiment in quantum physics. One of the important points of the theoretical experiment, which involves a cat in a box – along with a hammer, poison, Geiger counter, and a radioactive substance – is that one can only know what happens to the cat after the box is open. Until then, the cat is equally living and dead. Borrowing from that idea, Brazil’s former President Luis Inacio “Lula” da Silva is then the Schrodinger’s candidate: inside a box where his candidacy is (metaphorically) both alive and defunct.

Brazilians will choose their new president in October. According to recent polls from Datafolha and CNT/MDA, Lula is a clear leader. However – and where the first possible dramatic plot twist comes in – he might be in jail while running as a candidate. Adding yet another layer of complexity, regardless of whether he is in jail or not, no one knows if Lula will be able to be on the ballot, or take office if he were to win.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsA flash flood and a quiet sale highlight India’s Sikkim’s hydro problems

Ruling HDZ party wins most seats, but no majority in Croatia election

Croatians vote in election pitting the PM against the country’s president

The former president has been condemned for corruption changes linked to the large-scale Lava Jato (“Car Wash”) investigation. He is currently appealing the 12-year prison sentence and has denied all wrongdoings. On March 26, there will be a verdict on whether he waits in jail while his appeals are pending. But even if such decision is made, he will remain free – at least until April 4, when the Supreme Court is expected to vote the merits of his habeas corpus request. And as long as there are pending legal decisions in this case, even if the March 26th and April 4th decisions send him to jail, they do not automatically disqualify the former president from being a candidate.

According to Brazilian electoral laws, particularly the “Clean Record Law“ (Lei da Ficha Limpa) – which then President Lula himself sanctioned in 2010 -, a condemnation for crimes such as corruption and money laundering prohibits individuals from holding office. However, as long as there are pending recourses, the law allows individuals to register their candidacy and campaign normally. Therefore, in theory, the former president could be allowed to run his bid for a new term until the very last opportunity to appeal exists.

Many legally plausible mind-bending possibilities could emerge between campaigning and first and second rounds of voting. To start, Lula might have his request for candidacy rejected by the Electoral Court (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral), and not be allowed to be on the ballot at all – although he could appeal the decision. In another possibility, he could be on the ballot and lead in the first round of voting but be found ineligible to participate in the runoff, in which case all votes for him could be declared invalid, and the second-most voted candidate could win the presidency. In the most dramatic twist possible (even for Latin telenovela standards), Lula could win in the first round and later on be barred from effectively taking office, in which case the entire presidential election could be annulled.

For the former president and his supporters, the entire process is described as a sham to keep him out of the ballot and from returning to the presidency. For his critics, not only is he guilty, but deeply embedded in the many corruption schemes uncovered by the investigations. It will most likely be up to the country’s supreme court to give the absolute final decision on his case, which should take place within the next months. No matter how the Court decides at the very end, there will be vociferous cheers and boos.

When Datafolha asked the questioned “in your opinion, should Lula [sic] be able to run in this election?”, the division among Brazilians on Lula becomes evident: in a technical tie, 51 percent said he should not be able to participate in the election, and 47 percent said he should (two percent did not know/answer). Raising up this topic in family gatherings or friendly get-togethers among Brazilians is a sure way to instigate anything between intense awkwardness, tears, and fist fights.

Still, all of these speculations become moot points if Lula decides to drop off the process altogether and indicate a “by-proxy” candidate to run on his behalf. One can only wait and see what the next chapters of this Made in Brazil soap opera will reveal.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.