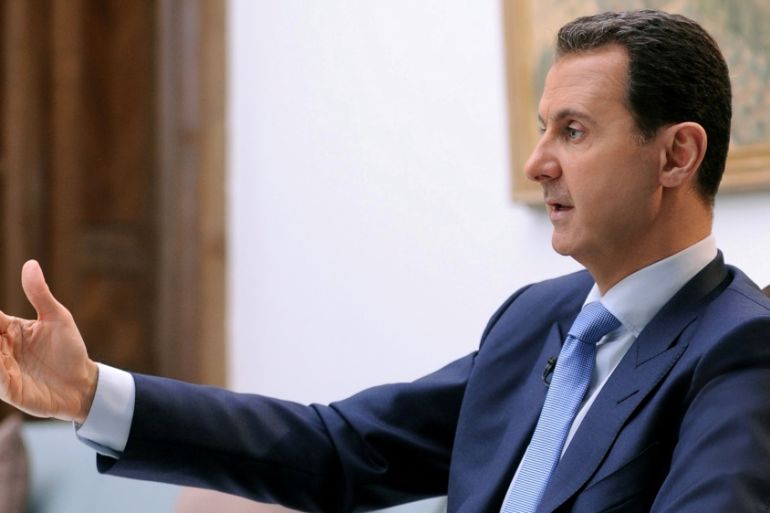

How Assad ‘won the war’

Bashar al-Assad is the president of occupied Syria.

“Al Assad has won the war,” declared Charles Glass in a recent piece for Stratfor, comparing the Syrian dictator to a Chicago mayor winning a re-election after cracking down on anti-war protests in the 1960s. In this rather bizarre attempt to draw a historical parallel, Glass misses an important point: Mayor Richard Daley did not have a foreign occupying power help him maintain a murderous regime against the wishes of Chicago residents.

And Bashar al-Assad has not just one occupying power on his side, but two: Russia and Iran. And while the two fight his battles for him in the east and south, Assad is able to put up a show of alleged stability in Damascus, where nightclubs opening their doors are impressing Glass.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe Take: Thirteen years later, has the world forgotten Syria?

Jordan army kills drug runners at Syria border amid soaring Captagon trade

Assad arrest warrant: ‘Hope and pain’ for Syrian chemical attack survivors

And when this all ends, unlike Daley, Assad will not have a popular mandate to rule; he is and will be a foreign-occupation-backed tyrant.

How Assad ‘won’ the war

In 2012 and early 2013, Assad’s regime was quickly losing control over rural territories across the country; desertion rates from his army for both regular soldiers and officers were skyrocketing as many refused to follow orders and shoot innocent protesters. At that time, the balance of power on the ground looked like it was leaning in favour of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and various Islamist groups, backed by Western and Gulf states.

That’s when the Iranians started coming. When Syrians from Damascus started reporting seeing them arrive by the busload in 2013, they were accused of exaggerating. By 2015 it was clear Iranians were fighting for Assad and not doing that well. So in July of that year Qassem Soleimani, breaking a travel ban, was dispatched to Moscow.

Two months later, Russia started its “air force only” “anti-terrorism” military intervention by bombing positions of the FSA. When opposition forces said they captured and killed a Russian soldier in late 2015, political analysts I know personally were quick to dismiss the opposition’s claims that Russian intervention had gone beyond air attacks and supplying weapons to the Assad regime, asserting that Russia would never actually take the risk of putting its soldiers on the ground in Syria.

Then, when the Russian and Iranian governments finally began to admit their soldiers were being killed in Syria on the battlefield, observers and media outlets could no longer deny that the occupation was far more entrenched than they had cared to acknowledge. Estimates from 2015 indicate that the regime’s manpower has dropped to somewhere around 80,000 troops. In 2016 Iranian fighters were estimated to number 70,000 (with Iran actually paying 250,000 fighters) and Russian fighters anywhere between 4,000 and 10,000, although Moscow is said to be supporting several regime-allied militias and military units as well.

These numbers are disturbing, but there are two other, more alarming trends emerging with regards to Russian and Iranian manpower in Syria. The first is the employment of marginalised groups in their home countries to fight for them in Syria, such as Iran’s Fatimeyon Force, which reportedly numbers around 20,000 Afghans (some forced into service facing threats of imprisonment), and Russia’s military police force, which has sent 1,200 Chechens and Ingush “volunteers”.

The second trend will have a more direct and long-lasting impact on Syria’s social fabric, increasing mistrust between citizens and threatening what is left of fragile Syrian bonds. Documents recently obtained by a Syrian opposition paper show that a defence ministry memo circulated in April 2017 refers to 90,000 Syrians fighting for local militias run directly by Iran and comprising of mainly Syrian Shia Muslims from both the civilian population and defectors or deserters from the Syrian Arab Army.

So long as Assad continues be an obedient tyrant, throwing contracts their way and allowing them to control not only their fighters, but also large factions of Syrian fighters, Iran and Russia can continue to implement their agenda in Syria.

The memo, which was reportedly presented to Assad, makes recommendations on how members of these militias should be treated and how the leadership could be brought closer to the regime’s own army. This seems to be a futile exercise because the loyalties of such militias now lie with Iran, who is paying their salaries while encouraging their participation in fighting based solely on sectarianism.

In other words, Assad is hardly in charge of what happens on the ground militarily.

Iranian and Russian ‘investment’ in Syria

Iran says it is intervening in Syria to support resistance against Israel and protect Syrian sovereignty, as well as preserve its own existence. Russia says it is intervening in Syria to stand against western imperialism and fight terrorism. But the reality is that their interventions-turned-occupations are not purely idealistic, noble policy positions: both are also profiting politically and economically from their interventions.

After Aleppo was devastated by these three actors (Iran, Russia and the regime) in late 2016, Iranian firm Mabna was awarded multi-million dollar contracts by the Assad regime to restore the electricity infrastructure in the city. In 2014 and 2015, reports began to emerge of Iranian traders buying not only shops and businesses in Damascus and Homs, but also farmlands and areas around religious sites.

The political and military gains are also significant for Russia. A deal signed with the Assad regime gives Russia control and access to its only naval port (the Tartus naval base) in the Mediterranean, as well as to the Hmaimim airbase in Latakia, for the next half-century.

After signing nearly one billion dollars in infrastructure deals with Russia by April 2016, the Assad regime, mere months later, then promised Russia priority in awarding contracts to rebuild infrastructure in Syria. According to Russian publication Fontanka, at least one Russian company has already acquired contracts giving it a 25-percent stake in profits from oil wells if it helps liberate and secure them.

But that’s not all. Russia is now seen as the point of contact for all things relating to Syria: even nations who have spoken out against Assad are now following Russia’s signals for next steps in Syria.

Put simply, it’s not just the military Assad has lost control of, it’s also the economy.

Assad must go, but so must Russia and Iran

It is impossible to reason with Syrians (and Arabs, for that matter) who continue to defend and support Assad and claim that it is because he stands against Israel and its occupation of Palestine. For some reason, they are blind to the fact that Assad is doing to Syria what Israel has done to Palestine, making it a land in which Iran and Russia are calling the shots and determining Syria’s future.

Currently, Assad is still being used by both Iran and Russia because so far, he has not disappointed them, a real-life example of the popular Arabic saying: they tell him to go left, he goes left; they tell him to go right, he goes right.

So long as Assad continues to be an obedient tyrant, throwing contracts their way and allowing them to control not only their fighters, but also large factions of Syrian fighters, Iran and Russia can continue to implement their agenda in Syria.

And if, at some point, Assad can no longer offer them these incentives, Russia and Iran have created an environment in which they do not need his presence to usurp what is left of Syria.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.