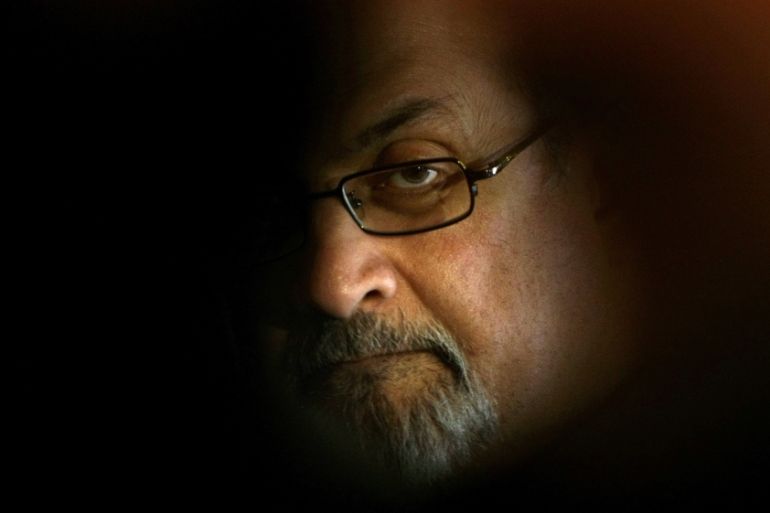

The life and death of Salman Rushdie, gentleman author

The man we call ‘Salman Rushdie’ today is not the brilliant author of the Satanic Verses, but a Picassoesque imposter.

In a recent flight, I was sitting a couple of rows behind Salman Rushdie on the British Airways flight 178 from New York to London. It was an eerie experience. On my way to the bathroom, I could see he was playing a video card game on his mobile phone. I was not even tempted to go forward and introduce myself. I can scarcely stand the man. Plus: can you imagine a bearded Iranian man approaching Salman Rushdie on a plane flying at 37,000 feet towards London. The man may freak out and relive the opening gambit of his Satanic Verses. Which one of us would be Gibreel Farishta and which Saladin Chamcha? Nerve-wracking!

I have met Salman Rushdie though, years ago when, in the heydays of the notorious edict (fatwa) against him, the late Edward Said had invited him to visit Columbia. I remember the small gathering Edward had arranged for him was literally behind closed doors and by invitation only. Perhaps a dozen or so Columbia faculty and students had gathered to chat with the author of The Satanic Verses while he was still in hiding.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsInside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

‘Accepted in both [worlds]’: Indonesia’s Chinese Muslims prepare for Eid

Photos: Mexico, US, Canada mesmerised by rare total solar eclipse

This haphazard encounter early in October 2017, however, coincided with the publication of Salman Rushdie’s most recent book, The Golden House, of which I was entirely unaware until I ran into a celebratory review in the Guardian – in which it was compared to F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited.

I dutifully went and purchased a copy of the book and began reading it and, yet again, I could not help feeling I was reading an impostor.

Why an imposter? Allow me to explain.

The birth of an author

I was still a graduate student when Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1981) appeared. Words fail to describe my joyous fascination in having discovered him. His voice was witty, brilliant, rambunctious, joyous – his prose revelatory, his politics familiar, his imagination trustworthy. I immediately placed him next to and up against VS Naipaul, whom the more I read the more I detested, especially after his horridly racist Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey (1981) that had come soon after the Iranian revolution of 1977-1979. Its sheer nasty arrogance could scarce conceal its ignorance of a revolution that had shaken my homeland to its foundations. My love at first read for Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children was no doubt in part animated by my revulsion against VS Naipaul. But long after my animus for Naipaul disappeared into indifference, my love and admiration for Midnight’s Children only increased.

I soon began reading the rest of Rushdie’s work – his first novel, Grimus (1975), his other magnificent fiction, Shame (1983), and his travelogue to Nicaragua, The Jaguar Smile (1987), which appeared as I was deep into writing my first book on Iranian revolution, Theology of Discontent (1993). Rushdie’s playful politics and his magic realism were palpable to me, happily familiar, a kind of Gabriel Garcia Marquez from my neighbourhood, I always thought. I basked in his nasty, naughty, joyous, playful, giggling, irksome prose.

This happy discovery of a new author continued well into the publication of his Satanic Verses (1988), of which I first read a review, I believe in Times Literary Supplement, upon its British release, which was before its US publication. I was so excited to read this new novel, I asked a friend in London to buy and send it to me to New York and I read it before it was published in the US. I found his Satanic Verses utterly magnificent, and I recall referring to it in a conference on Shia passion play at Hartford Seminary in Hartford, Connecticut, citing it as a perfect example of how old stories and even sanctities can be put into urgent contemporary (exilic) fiction.

Ever since one of his earliest 'posthumous' novels, The Moor's Last Sigh (1995), I have no longer been able to read Rushdie without a bizarre sensation I am reading an impostor.

Long after I could no longer stand Rushdie’s politics, I continued to include Satanic Verses in my various syllabi on postcolonial literature – marveling at while teaching the ecstasy of his prose – its virtuoso performativity, its bravura theatricals, its happy communion with English language, its bringing the Muslim sacrosanct forward for a rendezvous with a homely life away from home. Never ever (long after that horrid fatwa) did I think the novel an insult to Muslims. Quite to the contrary: it brought their sacrosanct to a renewed rendezvous with their history.

In retrospect, I am happy to have had that first undiluted encounter with Rushdie’s last novel before the whole hell broke loose on him and the rest of us who loved and admired his work. To this day, I read Satanic Verses with a fully conscious awareness of reading a great novel before it was sabotaged, verbally abused, narratively assassinated, and forever destroyed by one nasty ayatollah who had no freaking clue what the book was about.

The death of an author

The Guardian’s Emma Brockes recently said of Rushdie: “At 70, Rushdie has had more public incarnations than most writers of literary fiction – brilliant novelist, man on the run, subject of tabloid scorn and government dismay, social butterfly, and, in that singularly British designation, man lambasted for being altogether too Up Himself – but it is often overlooked what good company he is.”

I wish I could think of Rushdie that way: died and reincarnated multiple times. But alas for me, Rushdie died and never came back. As an author, he was born with that magnificent milestone novel Midnight’s Children and died after a blindfolded revolutionary zealot put a price on his head, killed his person, confused his persona, corrupted his politics, and turned what was left into a pestiferous Islamophobe on par and paired with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Sam Harris, Bill Maher and the rest of their detestable gang.

If you have “been” with Salman Rushdie as long as I have since his birth as a magnificent writer, and through his ordeal with Khomeini’s fatwa and subsequent moral degeneration into a bitter old Islamophobe, it is hard to resist the irrefutable feeling that the old ascetic Iranian Savonarola did, after all, manage to have the great inveterate novelist “assassinated” and what today we know as “Salman Rushdie” is a Picassoesque impostor – all his pieces might be there but the composition is contorted and grotesque.

Ever since one of his earliest “posthumous” novels, The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995), I have no longer been able to read Rushdie without a bizarre sensation I am reading an impostor. For that reason, I believe the writer who today goes by the name of “Salman Rushdie” offers literary theorists a unique case of “the death of the author”, as we say.

In 1967, Roland Barthes, the eminent French literary theorist, published his highly influential essay on the “Death of the author/La mort de l’auteur” in which he sought to decouple the autonomy of a text from the biography of its author. Though I find much interpretative energy lurking under the skin of Barthes’ proposition, I still believe something of the authorial voice remains in the text by way of our imagining an omniscient narrator behind any other narrator who is speaking the story to us when we read or watch or listen to a text. I cannot listen to Wagner or read Heidegger without thinking they were despicable anti-Semites.

My problem with Salman Rushdie’s fiction is I can no longer imagine that omniscient ventriloquist crafting a world for me to enter and believe, to possess and behold. I can no longer tell one from the other.

It is not that I don’t like Salman Rushdie as a person or that I loathe his politics as much as I do the politics of those who put a price on his head. It is that the words “Salman Rushdie” no longer simply refer to a person, an author, a novelist, for those two words have become an overload of thick and conflicting memories preventing any direct and unmitigated encounter with the novels, memoirs, and essays he writes, as Barthes tells us to do.

The fate of a nation

Salman Rushdie himself (or I should rather say “itself”) and that grand ayatollah who put a price on his head, both at each other’s throat forever, have become a thick text, standing formidably before the books he writes. Hard as I try, I cannot pass that repellent gate to get to the book he keeps writing.

That fatwa Khomeini issued against Rushdie has a far different tone to it in the ear of an Iranian who cares for the fate of his homeland. As the world attention was distracted by the smokescreen of a death sentence against a well-protected Indo-British author, Khomeini ordered the redrafting of an “Islamic constitution” (a contradiction in terms) into which now almost 80 million human beings are trapped. As European and North American liberals were falling head over shoulder to defend Rushdie’s freedom of thought, Iranian en masse were being subjected to a pestiferous theocracy to this day. For millions of Iranians, the downfall of Ayatollah Montazeri as a far more humane successor to Khomeini and the substitution of the vindictive Ayatollah Khamenei is the legacy of that so-called “Rushdie Affair”.

The moment I reach that historic cul-de-sac is precisely the instance I suddenly remember the Salman Rushdie I used to read when I first encountered his fiction. A sudden sadness, a moment of mourning nostalgia, then dawns on me remembering an author I once so joyously discovered, so dearly loved reading, and now having so sadly forever lost. Who is this strange man impersonating Salman Rushdie? He is “Salman Rushdie”, I then realise – forever condemned into two scare quotes, the signal citation of the fatwa a malignant man once issued against him.

As Salman Rushdie and I and the rest of the passengers on that flight between New York and London deplaned and entered Terminal Five at Heathrow Airport I was walking right behind him. He had put a light blue baseball cap on while walking on a moving sidewalk. At one point, he turned right towards the yellow sign for “Arrival” and I turned left towards the purple sign for “Transit”. He had reached his destination in London. I still had a long way to go somewhere else.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.