Putin vs Navalny: The street will decide

The presidential race in Russia has started and its outcome will be determined in the streets.

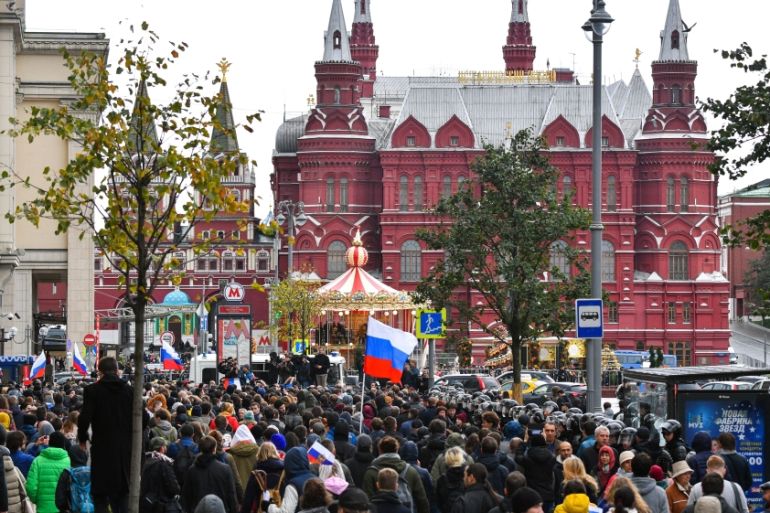

“Putin – thief!” were the chants Vladimir Putin had to hear on his 65th birthday. On Saturday, a crowd of mostly young people gathered under the Kremlin’s walls and on Tverskaya Street in central Moscow demanding that opposition leader Alexei Navalny (currently under arrest) be allowed to run in the presidential elections. Protests were held in dozens of other cities in Russia; some ended peacefully (like in Novosibirsk), others with mass arrests (like in St Petersburg).

In Moscow, this time there were very few arrested (all were released without charges) – either because the authorities didn’t expect so many people to show up that day they or because in advance of the 2018 FIFA World Cup, they are trying not to spoil their image. It seems that football has become the leading guarantor of the Russian constitution.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPutin: Concert hall shooting is act of intimidation by Kyiv

How will the Moscow concert hall attack affect Putin?

Moscow theatre attack suspects show signs of beating in court

|

|

Either way, it is clear that the presidential race in Russia has just started. It’s not important that Putin has not yet officially announced whether he would be running, and it’s not important that the Central Electoral Commission has already said that it will not allow Navalny to run (because of a conviction in a criminal case, which human rights defenders and the opposition have called fabricated). All this is not important because Russian elections are not like elections elsewhere where candidates compete.

Of course, in March 2018, when the elections are scheduled, there will be a formal choice between candidates. The majority of the people who will appear on the 2018 ballot have been “sparring partners” in elections since the 1990s (when the majority of Saturday’s protesters hadn’t even been born or were still in kindergarten).

Real opposition candidates have not been allowed to run for the presidency for many years now, which has led some commentators to say that elections have now lost meaning in Russia. But that’s not really the case. The presidential elections in Russia are very important; it’s just that they are conducted in the street and not at ballot stations.

If you take a look at the recent waves of protests in Russia, they always start just before the elections. That was the case, for example, with “the march of the dissenting” in 2007-2008, which was the first major protest in years to take place in a number of big cities. The scale of the demonstrations came as a shock not only to the authorities, but also the protesters themselves.

Then there was another wave of protests in the winter of 2011-2012 which drew even larger crowds. Some 100,000 people gathered on Saharova Boulevard in Moscow and demonstrations were held in almost all regions of the country. And again, neither the government nor the opposition actually expected such crowds. In the following few months, it seemed that the Kremlin’s grip on power had started to shake. Dmitry Medvedev, then formally the president, announced liberal reforms and state TV started inviting opposition leaders to speak on air. But immediately after the elections, the Kremlin rolled back the changes and tightened the screws again.

And now there is another wave of protests, and there is no reason to believe that it would be any weaker than the previous ones because old problems remain unresolved; the economic crisis continues, and the state of rights and freedoms in the country has worsened. In fact, there are seven factors which indicate that this wave will be even more powerful than previous ones.

Internal unity. Earlier, dozens of different small movements and parties were organising protest activities, and it was difficult for them to coordinate – they had different ideological views and were always bickering about political and organisational questions. This is now in the past. Who is “leftist”, “nationalist”, or “liberal” has been set aside because the main fight is against corruption, dictatorship and the absence of open political competition.

A new generation. This year’s protesters – compared with those of 2007-2008 and 2011-2012 – are remarkably younger. The majority of them are university and high school students. They actively use the internet and don’t watch TV, so they are immune to state propaganda.

|

|

The year 2017. One of the chants at Saturday’s protests was “Down with the tsar!” This year’s 100th anniversary of the 1917 Revolution has a peculiar psychological effect. All the historical discussions and projects dedicated to the revolution have made parallels between Putin’s regime and Nicholas’ II monarchy inevitable.

Active regions. The opposition in the past was never able to develop wide networks outside of Moscow and St Petersburg. Some parties did have regional representation, but it was mostly superficial and ineffective. Today, a strong opposition network exists in the regions – Navalny’s campaign offices. Judging by the fact that thousands show up to his rallies in cities across Russia, this network is in fact quite active and effective.

Putin has gotten old. When Putin came to power, his supporters were praising him as a young and energetic leader, while state propaganda was pushing pop hits by young girls singing about wanting a man “like Putin“. Today, Putin is 65 and at the end of the next presidential term (if he has one), he will be 71. The propaganda machine continues to organise topless photo sessions and hockey games, where he scores goals against professional hockey players. But today, all of this is just an infinite source of jokes and internet memes. And we all know that that which you laugh at, you cannot fear.

Available political alternatives. In the past, the Kremlin actively supported the slogan “If not Putin, then who?” suggesting that whatever other alternative candidates there were for the president, they were all worse. It worked because the opposition was divided and there was no leader who enjoyed overwhelming popularity – the Kremlin was organising effective discrediting campaigns against opposition politicians. Today, any attempt at discrediting Navalny actually works in his favour and boosts his popularity.

Network structure of protest. Paradoxically, the rise of a popular leader did not lead to a “personality cult” within the opposition. To the contrary – it led to the creation of networks which are able to act independently of leaders. The authorities have started court cases against many of Navalny’s top associates and before major protests, they are regularly arrested. That has not harmed the effectiveness of the protests because the networks are strong enough to proceed with activities in the absence of their leaders.

So will there be a new revolution in 2017? On both sides of the barricades, there is little belief that a revolution is possible at this time. Yet, it is worth remembering Vladimir Lenin’s hasty prediction “We, the elderly, might not live to see the decisive battles of this impending revolution.”

Roman Dobrokhotov is a Moscow-based journalist and civil activist. He is the editor-in-chief of The Insider.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.