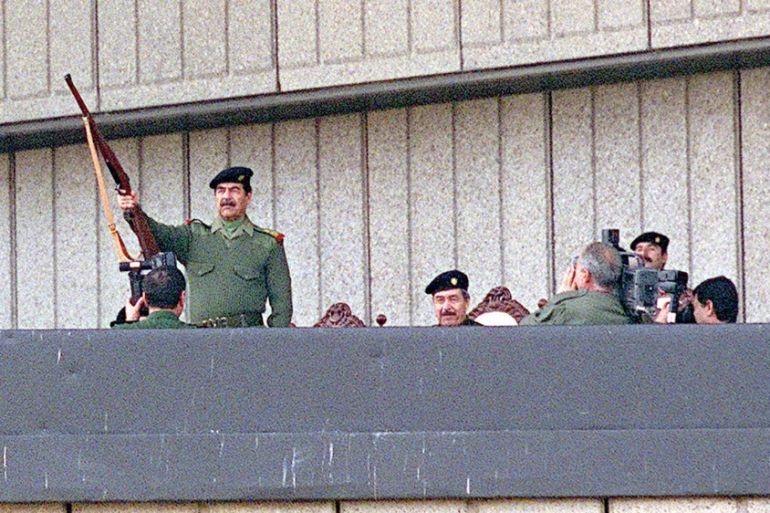

Saddam’s death gave birth to Saddams in other guises

A decade after the Iraqi president’s execution, a system that results in the daily deaths of Iraqis continues unabated.

On Saturday, December 30, 2006, the world awoke to the news of Saddam Hussein’s execution.

I learned of the news at 6:30am that morning, when I received a call from CNN’s Turkish affiliate in Istanbul to come on the air to discuss his death. 90 minutes later, the TV host concluded the interview by asking, “As an Iraqi, how do you feel after Saddam’s execution?”

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTwenty years on, John Bolton is still defending the US’s Iraq War

Iraq war: ‘The media ended up being lapdogs, not watchdogs’

‘He lied’: Iraqis blame Colin Powell for role in invasion on Iraq

I paused. Sweat trickled down my face, caked in make-up for the studio interview. I knew that some Iraqis would dance with joy, while others would weep. How did I feel?

“Empty”, I responded.

All I wanted was stability and a bright future for my ancestral Iraq. I knew Saddam’s execution would not bring that to Iraq, and a decade later, my desires still prove to be elusive.

The audiences of Saddam’s execution

A decade ago Saddam’s execution elicited mixed reactions among those living in Iraq and the region. Saddam managed to capture the imagination of the Arab public as the only leader who stood up to the West in two separate wars.

For those Iraqis who lost family to Saddam’s government, his execution served as closure with a bloody past. Yet, even those who despised Saddam admitted that he brought stability to the country, something that Iraq lacks today.

For those Iraqis who loved Saddam, they joined insurgent groups after 2003, hoping to return him to power. His execution did little to end their violence. Some of them, including former Saddam-era officers, eventually found their way to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), an organisation who had no love for the former Iraqi president, but emerged as the most effective insurgent group a decade after his death.

Saddam’s death and ‘The Republic of Fear’

In 1989, Iraqi-British academic Kanan Makiya published, The Republic of Fear, analysing how Saddam sat at the top of a system that inculcated an all-encompassing sense of fear in Iraq.

That fear knew no temporal or geographic borders. Even after Saddam went into hiding after the 2003 Iraq war, Iraqis were reluctant to cooperate with the United States occupation authorities, certain that he would somehow manage to return.

What is new to Iraq is insecurity, civil wars, car bombs, kidnappings, criminal gangs, ISIL and government mired by infighting among ethno-sectarian political factions.

That fear permeated beyond Iraq. Growing up in California, my parents hesitated to discuss their lives in Iraq, giving me the impression that it was some place they did not want me know about. They only discussed Iraq in whispered conversations that I overheard.

So, Iraq became something I only thought about, imagining how traumatic their past must have been that they could not even tell me. The mystery they created surrounding Iraq and Saddam Hussein only did more to enhance my curiosity. Saddam had been part of my life since childhood, then I studied his rule from my first days in college until I finished my PhD.

The more I studied his rule, I realised that Saddam sat at the apex of a system, in which thousands were complicit.

OPINION: Twenty five years later, the Middle East looks the same

The lesson of a paper I wrote on this system – one that was plagiarised by the British government on the eve of the 2003 Iraq War – was that there were thousands of Iraqis serving in the organs of the “republic of fear” who made it work. Killing Saddam would do nothing about these officials who would still live in Iraq.

With his execution Saddam’s republic of fear did come to an end. While Iraqis may have feared Saddam, a decade after his death they know new fears: a fear of getting killed by a car bomb on the way to the market; a fear of getting kidnapped and executed for being a Shia or Sunni; a fear that they will not find a job to feed themselves; a fear that they are stuck in a country with no future.

Saddam’s death and the ‘new Iraq’

After 2003, Iraq was often touted by the US news channels as the “new Iraq”, communicating that it had a bright and optimistic future. When 2006 came to a close, the new Iraq was free of Saddam. Yet, a decade after his death it is difficult to see what is optimistic about the “new Iraq”.

The new Iraq was touted as a democracy. Today it has the facade of democratic institutions with authoritarian practices in the shadows. The new Iraq was free of the Baathists. Yet, some Baathists also found a new home in ISIL.

What is new to Iraq is insecurity, civil wars, car bombs, kidnappings, criminal gangs, ISIL and government mired by infighting among ethno-sectarian political factions.

The expulsion of Iraq’s Christians from their ancestral homes, and genocide against the Yazidis; power cuts, lack of basic infrastructure; and a Mosul dam that could collapse at any minute; Saddam’s execution did nothing to prevent these developments.

OPINION: The enduring legacy of Operation Desert Storm

For some Iraqis, Saddam’s execution was a matter of justice for the mass crimes he presided over, such as the Anfal campaign, the chemical attack against Halabja, and the mass slaughter that followed the 1991 uprisings, which indiscriminately killed Iraqis of all ethnic and sectarian backgrounds.

A decade after Saddam’s execution, however, another Iraqi, Ibrahim al-Samarrai, otherwise known as Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the caliph of ISIL, is also presiding over an apparatus that targets Iraqis of all ethnic and sectarian backgrounds.

The justice some Iraqis sought proved ephemeral. In the vacuum that resulted from the overthrow of Saddam, another one emerged to replace him.

Ibrahim al-Marashi is an assistant professor at the Department of History, California State University, San Marcos. He is the co-author of Iraq’s Armed Forces: An Analytical History.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.