Casey report: The problem is more than integration

The reasons for the marginalisation of the working class have been economic and political, not a cultural loss.

“Drawing on what we have seen and heard during the review, we suggest integration is the extent to which people from all backgrounds can get on.” So suggests the Casey report, the latest British government study of the problems of immigration and integration (PDF).

Last year civil servant Louise Casey was asked by the then British Prime Minister David Cameron “to consider what could be done to boost opportunity and integration in our most isolated and deprived communities.” Her report was published last week.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsCyprus suspends asylum applications for Syrians as arrivals rise

Agadez, Niger’s gateway to the Sahara, finds new life in the migrant trade

Forced from home, these Colombians struggle to live in a basketball stadium

Even by the standards of government reports, Casey’s definition of “integration” – “the extent to which people from all backgrounds can get on together” – is particularly vapid. It well sums up both the tone of the report and of much official thinking on integration.

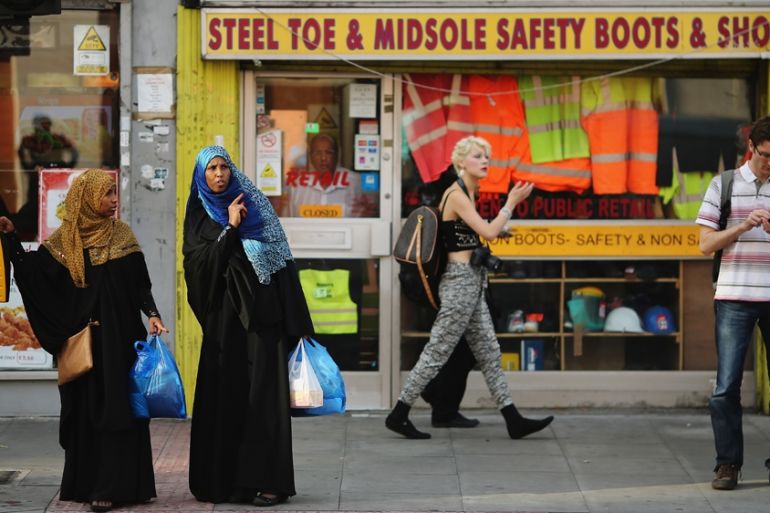

The central arguments of the report are familiar. Too much immigration and diversity, Casey suggests, has helped create segregated communities, with too many migrants who cannot speak English or are unwilling to accept British values. Muslims, in particular, are dangerously isolated, with a chasm between their values and those of society at large.

The findings

Casey certainly shows that there is considerable anxiety about the impact of immigration, though you would hardly have needed a year-long investigation to recognise that. What she does not show is that immigration is responsible for eroding social cohesion. In fact, much of the data in the report suggests the opposite.

Polls show that minorities, and Muslims in particular, have a greater attachment to Britain than does the population at large.

They also show that nine out of 10 Britons think that their community is cohesive, and their local area is a place where people from different backgrounds get on well together. Casey shows that this figured has increased (from 80 to 89 percent) since 2003.

In other words, Britons have become more positive about social cohesion in the very period in which “uncontrolled immigration” has supposedly eroded people’s sense of community and belonging.

Casey worries that there are 42 electoral wards in the UK in which “a minority faith or ethnic community had become a local majority of more than 50 percent”, that this reveals a high level of segregation. But that’s 42 out of a total of 9,196 electoral wards in the UK; put in context the figure seems far less alarming.

In any case, why should a high concentration of minorities signify a lack of integration? As Casey herself acknowledges, “high concentrations of minorities alone do not appear to be problematic for social cohesion between groups.” What matters are not the numbers, but the degree of integration.

READ MORE: UK government report slams migration ‘failures’

One of the signifiers of greater integration, Casey suggests, is greater inter-ethnic friendship. But she also points out that whereas half of first generation migrants have friends from other ethnic groups, three-quarters of the second generation do so. Inter-ethnic friendships, in other words, increase over time.

And which group is least likely to have inter-ethnic friendships? Not an immigrant group, but white British, just four percent of whom have such friendships. Proportionately, twice as many Bangladeshis and Pakistanis and three times as many Indians do so.

This might be expected given that white British constitute the largest group and hence are less likely to meet people of other ethnicities. Nevertheless, it should again make us think more carefully about the relationship between immigration and integration, certainly more carefully than Casey does.

The need for conflicting views

The problems of the Casey report reflect broader issues with the discussion about immigration and integration. There are two fundamental problems at the heart of most such discussions today.

The first problem is the view of conflict as bad in itself. Integration is seen as a way of minimising social conflict and of getting people to hold broadly similar views and values. But conflict is not necessarily bad. Nor is disagreement over even the most fundamental of values a sign of lack of integration.

From a liberal viewpoint, the attitude of many Muslims towards homosexuality or women’s rights are troubling and needs challenging (PDF). But holding illiberal views is not the same as failing to integrate. That is why many Muslims are socially illiberal and yet feel British and integrated.

The question of immigration and integration and that of wider social disaffection are usually only ever linked to suggest that too much immigration helps create disaffection. It is an argument that fails to understand the problems facing both minority and majority communities.

Certain forms of conflicts – physical confrontation on the streets, for example – are problematic. But conflicts over values, beliefs, ideals, are essential to a flourishing society. Only the existence of a diversity of conflicting views allows us to have our own views challenged and creates the possibility of progress and change. Such conflicts are the raw material of political and cultural engagement.

The real problem is not conflict itself, but the form that it takes. Ideas about “us” and “them” have transformed in recent years. Social solidarity has become defined increasingly not in political terms, as collective action in pursuit of certain political ideals, but in terms of ethnicity, culture or faith. Many within minority communities want to find themselves and their place in society through a sense of their difference from other communities and groups.

OPINION: Don’t ditch diversity because progressives failed

In this process, social problems that were once seen as political issues have come to be reposed as cultural differences. Political struggles divide society across ideological lines, but they unite across ethnic or cultural divisions; cultural struggles inevitably fragment. Conflicts have become more intractable and channelled into forms that are neither useful nor resolvable.

Social policies have only exacerbated this process. “Multicultural” policies have tended to manage and institutionalise diversity by putting people into ethnic and cultural boxes; defining needs by virtue of the boxes into which people have been put, and using those boxes to shape public policy. The result has been to exaggerate conflicts over identity and to foster a greater sense of division. It is this, rather than immigration or diversity, that needs to be tackled.

Disaffection at the centre

The second key problem is that the debate about integration ignores wider questions of social fragmentation.

The issue that has dominated the news recently has been the growing disaffection of large sections of society with mainstream institutions, and the creation of more fractured societies in which many – particularly traditional working class communities – feel politically abandoned and voiceless, ruling elites seem out of touch, and people inhabit myriad echo chambers – deaf to the views and values of others.

All this has led many to reject the kinds of liberal values that defined post-war Western societies, fuelling the rise of populist and far-right groups.

Just as many within minority communities understand themselves primarily in terms of identity and difference, so increasingly do many in majority communities.

OPINION: How Europe’s far-right feasts on Trump’s victory

The reasons for the marginalisation of the working class have been economic and political, but some have come to see it primarily as a cultural loss. Some look upon minority communities primarily through the lens of their “difference”, and have come to see immigration as eroding national culture, history and heritage, and hence as a threat to be resisted.

The question of immigration and integration and that of wider social disaffection are usually only ever linked to suggest that too much immigration helps create disaffection. It is an argument that fails to understand the problems facing both minority and majority communities.

There are certainly issues specific to immigrants and minority communities. But unless these are understood in the context of the wider problems of social fracturing and disengagement, we will continue to be blind to the real issues facing both minority or majority communities, and be left with merely the banalities and prejudices of such as the Casey report.

Kenan Malik is a London-based writer, lecturer and broadcaster. His latest book is The Quest for a Moral Compass: A Global History of Ethics. He writes at Pandaemonium: www.kenanmalik.wordpress.com.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.