Egypt: Making art public

Street artists seek validity through the public’s appreciation, rather than formal art institutions.

Many of Egypt’s revolutionary activists claim that the 2011 uprisings were not simply about former President Hosni Mubarak.

They were about placing power and resources in all spheres in the hands of the public. In the cultural sphere, art is a contested domain.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsInside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

‘Accepted in both [worlds]’: Indonesia’s Chinese Muslims prepare for Eid

Photos: Mexico, US, Canada mesmerised by rare total solar eclipse

In Egypt, official institutions – government and private, domestic and foreign – play an acute role in the arts by virtue of their positions as the funders, promoters, critics, and censors of art.

These institutions have the ability to select, feature, explain, and thus, determine the legitimacy, value and utility of art.

What constitutes real art, real artists, and valid analyses of that art is up to these institutions – giving them extensive power.

Appreciation of the public

Many street artists in Egypt contest the role of these institutions in determining the legitimacy of art and seek to hand that power to the public.

Even prior to the 2011 uprisings, artists opposing the state’s domination of art created and presented their works on busy urban streets, rather than in art galleries.

While many galleries are public – and are available at a low or no cost – they are socially viewed as a luxury and are frequented by limited social demographics.

|

Ammar Abo Bakr is one opposition artist who seeks to root his work in popular tradition and make it broadly accessible. He has painted several street murals with the objective of exposing the public to art.

|

Even if attended by various social groups, viewers are not acknowledged as truly understanding or appreciating the art, unless they are capable of speaking about it in certain terms.

Thus, there is not only a hierarchy of legitimate art, but of legitimate viewers as well.

By presenting their work in a more accessible space, street artists sought validity through the public’s appreciation rather than through formal institutions and their narrow audiences.

In terms of substance, art that is selected by official institutions and art created by oppositional artists significantly diverge in Egypt.

While modernist art trends have subsided in many parts of the world and given way to post-modern or contemporary genres, they remain heavily promoted in Egypt by domestic and foreign art institutions.

This modernist art, which claims to adhere to the impossible ideal of separating itself from its context, tradition, or any utilitarian purpose is prioritised, and ironically, made into a valuable commodity in the mainstream Egyptian art scene.

To these institutionalised artistic bodies, the ideal modernist art piece is abstract, universal, and purposefully veers away from the narrative approaches often found in traditional Egyptian folk art.

Arguably, these modern institutions want to take Egyptian art away from its contemporary politically and socially utilitarian approach.

Enter street art

The effect of this global modern art movement’s influx into Egypt has been selective marginalisation of works with critical political or social meaning – meanings that are relevant to the realities of given localities within Egypt.

This impedes the potential for art to educate, inspire, or call the public to action – a goal that is aligned with any government body seeking to maintain the status quo.

Ammar Abo Bakr is one opposition artist who seeks to root his work in popular tradition and make it broadly accessible. He has painted several street murals with the objective of exposing the public to art.

Conceptually, Abo Bakr claims inspiration for his murals from the popular rural tradition in Egypt of painting on walls to mark occasions, such as villagers’ return from the annual Hajj pilgrimage.

|

|

| Listening Post – Feature: The power of street art |

He painted his first public mural in the summer of 2013 on a concrete wall on Qasr al-Nil street in downtown Cairo.

The piece featured images from Egypt’s Pharaonic, Coptic, and Arab-Islamic heritages in celebration of Egypt’s historical and cultural diversity. The mural was in opposition to art institutions that either completely overlook or narrowly select from the country’s artistic repository.

The location and content of the piece were notably unconcerned with the dramatic political struggle taking place at the time. It wasn’t overtly political in nature, but rather, it centred on taking the power away from artistic institutions and bestowing it upon the Egyptian public.

Abo Bakr’s most recent street mural, finished in May, is also in downtown Cairo on a concrete fence bordering a car park area.

The purpose of this piece is similar to his other piece: to share art with the people.

However, this piece exists in a more security-focused downtown Cairo, where any unofficial activities or gatherings are strictly limited.

Securitisation of Cairo

In recent months, downtown Cairo, a major site of the 2011 uprisings, has witnessed major shifts in pavement and street traffic.

Tightly enforced bans have eliminated the presence of street vendors and pavement cafes, where many activists previously met.

These bans seem to be tied to security issues and the prevention of any sort of social gathering that may lead to mobilisation for political ends.

To avoid security threats, Abo Bakr shifted tactics: rather than painting his piece directly on the walls, he printed the mural in large strips that could be quickly adhered to the walls to avoid the attention that the time-consuming process of painting would draw.

RELATED: Egypt’s graffiti artists make their mark

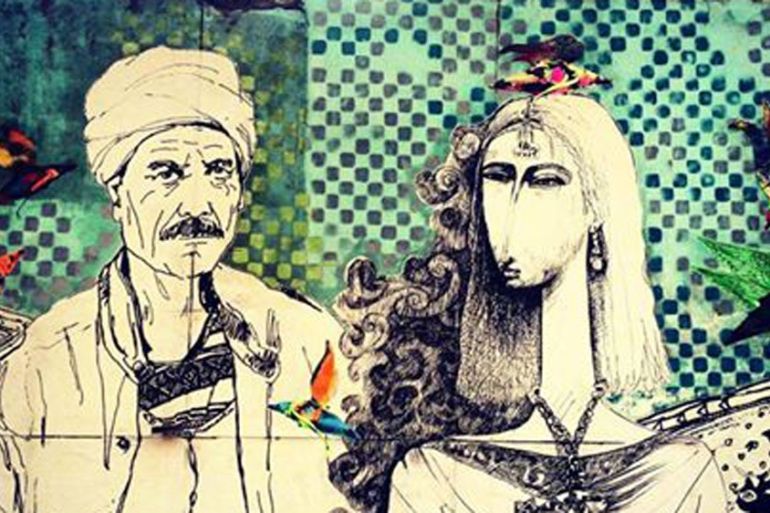

The piece itself is not overtly political. It is a collaborative one between Abo Bakr and a surrealist artist featuring black and white drawings of a man in traditional Egyptian clothing and a woman adorned by hair mimicking the sea and wide-spanning wings.

The images are placed within a backdrop of coloured squares and winged creatures.

Rather than engaging vendors who wanted their kiosks painted for passers-by frequently interested in watching the process, Abo Bakr avoided contact while working so as to not draw attention or incriminate others.

Still, he was caught in the act and is currently facing charges for vandalising public space.

Abo Bakr’s two street murals discussed here are avidly post-modern.

They are realist rather than abstract and borrow from traditional art practices.

They are utilitarian: They seek to maintain and develop upon local art forms, engage the public in the process of creating art, and reject the institutional and classist advancement of abstract, purposeless art forms.

They are tied intrinsically to their setting. A true appreciation of Abo Bakr’s work does not require access to a particular set of art terms in the way that modern art does, but rather, an understanding of local context.

For many independent street artists in Egypt, the battle, which predates Mubarak, continues.

This battle opposes a pattern of institutional practices aimed at marginalising politically or socially utilitarian work and promoting art solely as a universal and timeless form of individual self-expression, rather than a communal element of its particular context.

By doing so, these institutions marginalise local art forms, empty art of political and social purpose, and tinge art with classist barriers.

Sarah Mousa graduated from Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs in 2010 and was a 2010-2011 Fulbright Scholar in Egypt. She is currently a graduate student at the Center of Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.