It’s the faculty, stupid!

The goal for institutes of higher learning should be to educate students to become autonomous and thoughtful citizens.

We all remember when Democratic strategist James Carville coined the famous phrase “it’s the economy, stupid”, for Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign. It quickly became a slogan often repeated in US political culture. Together with the economy, he also emphasised the significance of “change” and “healthcare”. While Obama seems to have taken these latter two items to heart, education (in particular in the humanities) still seems to be a marginal issue among his priorities. This also occurs with other politicians. But why is it so common today?

For those of us who had the good fortune to be educated by teachers who guided our intellectual interest and social wellbeing regardless of where we were enrolled, we know it’s always the faculty that makes the difference, not the institution. If, as Noam Chomsky once pointed out, “our kids are being prepared for passive obedience, not creative, independent lives”, it’s because we live in a corporate world where most institutions are ranked according to criteria that too often ignore the essence of the discipline in favour of the job market.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Triple spending’: Zimbabweans bear cost of changing to new ZiG currency

‘We share with rats’: Neglect, empty promises for S African hostel-dwellers

Thirty years waiting for a house: South Africa’s ‘backyard’ dwellers

It is also interesting to notice how the failure of MOOCs (massive open online courses, which represent corporate universities’ latest development), lies in the impersonal nature of the courses – because students are unable to meaningfully interact with their professors, one of the fundamental aspects of any serious education. This is why, as Sarah Kendzior brilliantly explained, colleges must be “reformed, not replaced”. How can we reform our higher education system? And why is it necessary?

Soundbite culture

One of the most critical challenges to serious education is the soundbite. Although the soundbite was coined in the 1980s during Ronald Reagan’s presidency, its logic emerged in the 1960s, in the merger between the advertising industry and politicians, with the sole purpose to sum up complex political platforms with a single fragment. Jeffrey Scheuer’s 2001 book, The Sound Bite Society, argued that television damaged a society’s ability to discuss complex political issues, replaced it with the instant satisfaction of titillating turns of phrase. The fragment thereby hijacked serious social discourse through insultingly simplistic phrases.

But suppose we take Scheuer’s thesis to its limit and claim that this same reduction has equally limited the ability to reflect deeply about any issue at all. Dr Michael Rich, the executive director of the Center on Media and Child Health in Boston, says young people’s “brains are rewarded not for staying on task but for jumping to the next thing” and so, “[t]he worry is we’re raising a generation of kids in front of screens whose brains are going to be wired differently”.

This trend is not necessarily a bad thing because the focus is on connection-making, which trains the mind to be open to new thresholds and new concepts. There is a political dimension to a soundbite culture that shapes how we think about the world. And if we are trained not to think in a sustained and serious way, then the underlying power relations will go unchallenged.

|

Colleges and universities are actively undermining one of their basic tenets – to educate and equip a citizenry to make society a better place, in great part by challenging unjust and abusive power. |

The fear here is that colleges and universities have jumped too quickly onto this “shallow and fragmented” trend, in which the very framing of learning communities is geared to constant interruption, structurally and environmentally subverting a serious learning environment in which the virtues of critical thinking are severely compromised.

In other words, colleges and universities are actively undermining one of their basic tenets – to educate and equip a citizenry to make society a better place, in great part by challenging unjust and abusive power. When you combine this unreflective and shallow environment with the corporate takeover of the academy, you turn the education process into a means to make more and more profit. A profit mentality driving the educational environment will necessarily ignore building a conscious community that is intentional about learning, and serious about forming citizens who can think critically and question society. To do that, learning environments must be intentionally formed so that students can learn to focus on serious and sustained reflection.

Reforming higher education

One way to shape students is to set standards high. But this is only as effective as the faculty. If the faculty is bullied by administrators to “make a buck” in the classroom, that university will fail at its basic mission. But if you have a faculty that is bold and creative about learning, then you will have students who will emerge from university with a determination to make society more democratic by challenging unjust power.

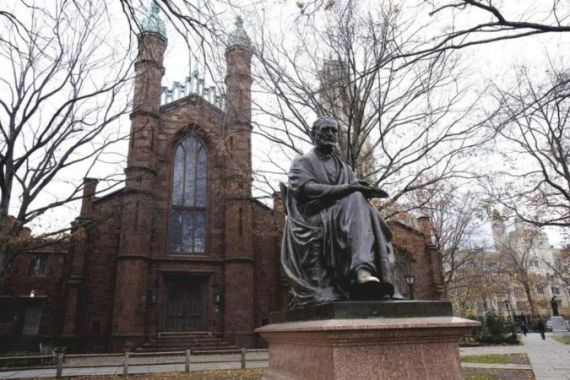

The academy needs to be reformed because it fails to train citizens to question authority – because rich boards of directors want to make more and more money. Higher education today, as Kendzior critiques, “is less about the accumulation of knowledge than the demonstration of status – a status conferred by pre-existing wealth and connections. It is not about the degree, but the pedigree.” This ideology often leads universities to promote their brand over their faculty, ignoring the fact that their very brand is a consequence of the faculty, not the other way around.

This is why we must welcome independent institutions such as the EGS (European Graduate School) and the GCAS (The Global Center for Advance Studies), where the primary concern is the quality of the faculty rather than the institution’s brand. Although there are a number of differences between these and other independent institutions, they all choose their faculty in order to provide their students with academics who will not simply “teach in order to educate”, but rather “educate in order to think”. The difference between both principles is particularly evident in the humanities, where students are often requested to become consumers of information rather than autonomous interpreters.

While promoters of the first principle will invite students to choose Ivy League universities regardless of the discipline that interest them, those of us who focus on the faculty will invite students to follow particular economists, scientists and philosophers, regardless of where they teach. Creston Davis, the co-founder of the GCAS as well as a serious philosopher, explains how:

The aim of the GCAS is not to replace established universities or colleges, but rather to offer an alternative for those students who wish to study with internationally recognised academics in the same MA or PhD program. These programs will take place in a series of locations throughout the world giving them the opportunity to interact with local academics and intellectuals. We do not want to generate students, but rather disciples able to develop the thought, views and projects of our great faculty.

If we agree with Philip G Altbach, the director of the Center for International Higher Education of Boston College, when he says: “It’s the faculty, stupid!“, then the EGS, GCAS, and other independent institutions are probably the right way to begin reforming our higher educational systems. These institutions represent ways we can reform and overcome the soundbite culture and promote emancipation through education.

Santiago Zabala is ICREA Research Professor of Philosophy at the University of Barcelona. His books include The Hermeneutic Nature of Analytic Philosophy (2008), The Remains of Being (2009), and, most recently, Hermeneutic Communism (2011, coauthored with G. Vattimo), all published by Columbia University Press.