What the Abbottabad report means for Pakistan

The bin Laden report confirms the mutual disdain Pakistan and the United States maintain towards each other.

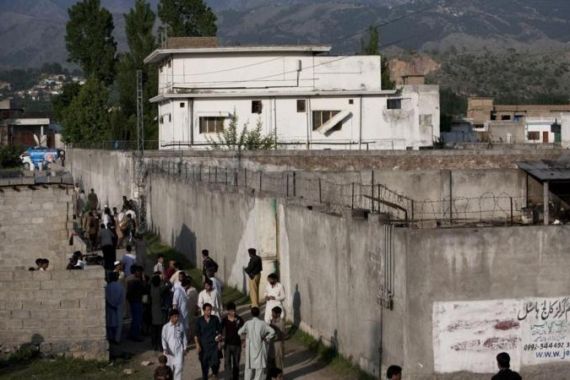

Growing up as a schoolboy in Abbottabad in the late 1950s, I would often spend late lazy Sunday afternoons in summer with friends looking for tadpoles and fish in the cool streams and pools of the valley. Little did I know at the time that this very spot would one day house the most wanted man in the world – Osama bin Laden – and bring the attention of the world to it.

With the leaking of the 336-page Abbottabad Commission report in recent days by Al Jazeera, we are able to look back at the extraordinary events that led to the killing of bin Laden by US Navy SEALs on May 11, 2011. To have found in the midst of the idyllic surroundings of the Abbottabad valley a man wanted for murder and mayhem and hunted by the world strains the credibility of Pakistan’s security and intelligence forces.

|

It is also noteworthy that the report, having been withheld by the government from the public domain for the past six months, was leaked |

I am astounded, having also served as Assistant Commissioner in Abbottabad as part of the Civil Service of Pakistan, how the local authorities could not detect his presence. The Pakistan Military Academy is in close proximity to the house in which he was hidden, and the cantonment town, settled primarily by retired military officers, is a centre of major military bases for several of the more famous Pakistani regiments.

That is why the Commission report is so harshly critical of the intelligence and government agencies of Pakistan who failed to fulfil their responsibilities, finding “culpable negligence and incompetence at almost all levels of government”. It clearly points to the ineptitude and dereliction of duty of various officials. But what about the question of complicity?

While the report hints at the possibility of some degree of connivance on the part of the Pakistani government, the report does not push this argument much further. The Abbottabad Commission report does, however, have historical importance for Pakistan. In the context of Pakistani history, the report is both courageous and honest in its assessment of Pakistani failures and attitudes concerning the raid that killed bin Laden.

It states that this was the greatest national humiliation since the breakaway of East Pakistan in 1971. There is little hesitation in its critique of the Pakistani intelligence and strong recommendations for transparent civilian control in the government over the nation’s security and defence.

Relations between Pakistan and the United States, as attested to in this report, hit rock bottom after the raid. The visceral dislike of Americans is reflected in a number of interviews. The head of Pakistani intelligence stated that American arrogance knew no bounds. It is scathing in its critique of the Americans, referring to the raid as an “act of war” and called the killing of bin Laden “a criminal act of murder” by the US president.

The report also mentioned other events over past years which have fanned the flames of discontent among Pakistanis against the Americans, including the Raymond Davis episode and the on-going drone strikes in the Tribal Areas.

In effect, the report confirms the views each country has of the other: Americans viewing the Pakistanis as duplicitous and incompetent (exemplified by Richard Clarke’s declaration that Pakistan is “a nation of pathological liars” on the Bill Maher Show) and Pakistan viewing the Americans as infringing on their country’s sovereignty for their own strategic interests with little concern for the people of Pakistan. The report recommends that the relationship between the two countries should be based on mutual interests.

It is also noteworthy that the report, having been withheld by the government from the public domain for the past six months, was leaked. In contrast, the Hamoodur Rahman Commission report on the events of 1971 in East Pakistan was locked away for decades. We still do not know the details of Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto’s murder in 2007 despite several commissions assigned to study the incident.

Moreover, the report sheds fascinating light on Osama bin Laden in his last years. Walking about in one of his six shalwar kameez, three for summer and three for winter, and wearing a cowboy hat to avoid detection from satellites, he lived a life of austerity and simplicity with few possessions and largely cut off from the outside world.

He was affectionately known among the children of his family as Miskeen Kaka, literally meaning “poor/helpless uncle,” a term with religious undertones which implies endearment and respect. It is ironic that the most wanted man on earth who had struck such fear in the hearts of millions of people and whose actions triggered murder and mayhem across the globe, lived like a destitute recluse and had become almost entirely irrelevant to al Qaeda.

|

|

| Pakistan remains silent on Bin Laden report. |

The report confirms that Osama bin Laden was not the evil mastermind guiding an international network of “linked” terrorist groups locked in a clash of civilizations as so many commentators have portrayed him over the past decade. The violent acts of terrorism erupting like brush fires across the Muslim world, the TTP in northern Pakistan, Boko Haram in Nigeria, and Al Shabab in Somalia, for instance, are a result of their own local and historical background, mainly the conflict between tribes on the periphery and the central governments.

The fact that the killing of Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad did nothing to abate the violence across the Muslim world is evidence enough that a new paradigm based in understanding local history and culture is needed for understanding the war on terror that has so negatively impacted large swathes of the world.

If that young schoolboy hunting for tadpoles in the pools and streams of Abbottabad found himself in the same place today, he would not recognise it. The war on terror had come to this idyllic town, like much of the Pakistan I have fond memories of from my youth, and changed it beyond recognition.

Ambassador Akbar Ahmed is the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at American University in Washington, DC, former Pakistani High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, and author of The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam(Brookings 2013).