Ballot wars: The Iranian public strikes back

The Iranian people took the quill from Khamenei’s hand and are now attempting to write their own future.

On the same day that the United States announced it would be sending arms to the opposition in Syria, a massacre took place in Syria, Iraq was roiled by sectarian violence, and Afghans were struggling to survive the corruption of their government.

In the midst of all this carnage and catastrophe, Iranians took time off from their daily chores to go out and vote for their next president.

This election began as all others – the ruling administration staging yet another spectacle to show its legitimacy – but it got more than it bargained for.

Already on Al Jazeera’s website you have read two accounts of this election, one by a group of entirely discredited expatriate opposition members who call this election a sign of a “phony democracy“, and the other by an ex-CIA agent and his ex-US State Department “Iran expert” wife who think the Islamic Republic is the grandest thing that happened since the sliced bread they share on their frequent flights to Tehran.

One simple fact underlies both these patently opposite accounts: they are both, as a matter of academic education and scholarly credentials, given by persons illiterate in Iranian history and political culture.

I have already attended (on more than one or two occasions) to the discredited expat opposition and their treacherous complicity in calling for even more crippling sanctions or even a military strike against Iran, as I have exposed the moral and political bankruptcy of the PR machinery on a rampage to discredit the Green Movement in Iran.

For now, I refer you to the magnificent review of one of their nauseating atrocities by the distinguished journalist Roger Cohen.

Now we have a far more urgent task at hand: understanding one of the most dramatic political events in Iran since the Green Movement of 2009 – understanding it, that is, from the vantage point of a reasoned, informed, and balanced perspective, and not discredited partisan propaganda.

To vote or not to vote

Millions of Iranians flocked to the polling stations on June 14, a fateful day that followed months of gut-wrenching debates between those who wanted to go back to the ballot boxes – no matter how undemocratic the vetting process – and those who were adamant that after the 2009 elections they would never again vote in this horrid Islamic Republic (for an excellent chronology of events that led to the massive participation in the election, see here).

|

|

| Hassan Rouhani wins Iran presidential election |

Of Iran’s 50 million-plus eligible voters, about 36 million participated, of whom more than 18 million voted for the winner, Hassan Rouhani (for identical numbers from two opposing sources citing the Ministry of Interior, see here and here).

These numbers are important, mainly due to the arguments that those who didn’t vote for him were probably going to vote in the polls regardless of the contenders, as opposed to those who did vote for him, who were probably embroiled in a heated and purposeful debate on whether or not to even bother voting.

What ultimately turned the table towards voting was not any heated discussion among the leading intellectuals, or even the ordinary people – though there were some delusional Don Quixotes on Facebook who thought their “status updates” from the US or Canada or Europe encouraging voting for Rouhani was chiefly responsible for the heavy turnout.

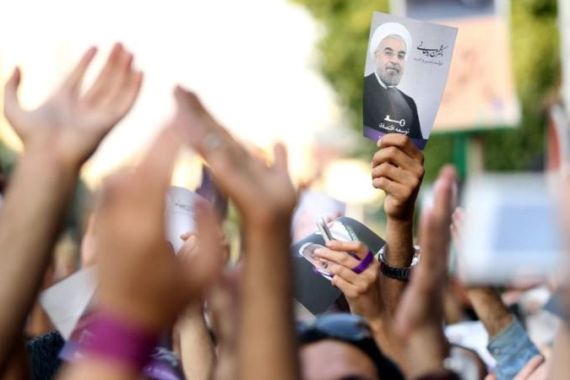

Instead, young and old Iranians, men and women, went to campaign stumps of their favourite candidates and partook in what Hannah Arendt calls “public happiness”.

While all candidates had their own supporters and diehards, it was Hassan Rouhani who, before he knew it, was flooded by cries of “political prisoners must be freed!” or “ya Hossein, Mir Hossein“, an ingenious fusion of a Shia invocation and a reference to Green Movement leader Mir Hossein Mousavi.

For the moment, it did not matter that Rouhani did not reciprocate these cries and remained deafeningly silent in response.

The die was cast – people were out in the public domains and claiming their space. Suddenly June 2013 looked, sounded, and felt like June 2009. Though he scarcely mentioned Mousavi or Karroubi by name, Rouhani otherwise rose to the occasion and touched many bases: demilitarising the public space, returning joy and energy to university campuses, attending to women’s rights issues, and following a nuclear programme that was not at the heavy cost of other Iranian interests.

The Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, tried to micromanage the election, but the intention of Iranian citizens went far beyond his or anyone else’s control. People, in their collective actions, took the pen from Khamenei’s hand and authored their own history.

How to outwit a tyrant?

In Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921), the curtain rises for the audience to see a theatrical company getting ready to rehearse Pirandello’s own play The Rules of the Game (1918-1919).

As the rehearsal is getting under way, suddenly six strange characters appear onstage and rudely interrupt the rehearsal.

The cantankerous director, incensed by the intrusion, asks who they are. One of them says that they are six unfinished characters in search of an author to finish them.

|

|

| Inside Story – Iran: A victory of moderation? |

That by now legendary opening gambit of what later would develop as the “absurdist” movement in European theatre just had a real life simile in the course of the presidential election in Iran, when eight “unfinished” presidential candidates entered the Iranian stage; the contenders, undaunted by the absurdity and handpicked by the Guardian Council to meet the strict demands of clerical rule, searched for a way to complete their characters and have one picked, reinvented and delivered unto history.

Forget about Rouhani – the Iranian public effectively told Khamenei and the Guardian Council: “You give us the proverbial Molla Nasreddin (a popular folkloric character) and we will turn it into the poster boy of our democratic hopes and dreams.”

It makes absolutely no difference if Rouhani delivers or not on his campaign promises (though in his first nationally televised address to the nation, he has specifically promised to do so) – what matters is that people used the small crack the ruling regime offered them and turned it into what Elias Canetti calls “people power”.

Pursuit of public happiness

What we witnessed during this and previous Iranian presidential elections is how the superior social intelligence of a democratically defiant public takes what the theocratic regime throws its way, breathes new life into it, and creates their own leaders.

They did this with Hashemi Rafsanjani in 1989, soon after the devastating Iran-Iraq war; in 1997 they did this with Khatami; in 2009 with Mir Hossein Mousavi; and now in 2013 the same with Hassan Rouhani.

How this democratic will performs, conscious of its public power, is a lesson for our understanding of the larger democratic tsunami that is running its course through the Arab and Muslim world.

For four gruelling and punishing years, Iran has been in a state of limbo: Mir Hossein Mousavi was under house arrest, scores of democracy activists were subjected to kangaroo courts and jailed, the Khatami-led Reform movement had been rendered obsolete by the far more potent and progressive Green Movement, all while Ahmadinejad’s divisive presidency created infighting among the conservatives.

When this presidential election began, the Reformists at first hoped to beat the dead horse of their cause and get Khatami to run. He wiggled for a while, but then wisely realised he wasn’t the man for the job, while Mousavi was alive and well under house arrest.

Then the outmanoeuvred Reformists began placing wagers on Hashemi Rafsanjani, but he too was roundly rejected by the Guardian Council – an exceedingly important development that requires a critical reading of its own.

So the discredited and outmanoeuvred Reformists entered the race with the feeble figure of Mohammad Aref, of whom they are now trying to create a national hero after he dropped out of the race to help Rouhani, before the main body of the Greens finally resolved to flock around him.

This extraordinary ability of the public to transform politicians into the personification of their democratic or rebellious will has a magnificent antecedent in 19th century Iran that is even more radical.

During the Tobacco Revolt (1890-1891), there was a famous fatwa issued by Ayatollah Mirza Hassan Shirazi against the use of tobacco that was widely believed to have inaugurated the revolt.

To this day, many historians are not quite sure that Shirazi actually issued that fatwa, or whether it was the collective will of the people in Shiraz that wished and willed it to have been issued.

In this most recent election, the democratic will of the people was even more pronounced.

Those who did not vote told Khamenei he could not get away with murder – he could not order the maiming and murdering of people in 2009, incarcerate and torture those who object, put the symbolic leaders of the Green Movement under house arrest and then in 2013 come back and call on them to vote.

Those who voted, meanwhile, told Obama and his allies that Iranians are perfectly capable of using whatever means available to manage their own democratic future.

It does not matter that people are out in Gezi Park but not in Azadi square. In this grand chorale of democratic uprising in the Arab and Muslim world, each nation does what it does best – and they will all benefit and learn from each other.

The Egyptians and Tunisians do one thing, the Turks another, and the Iranians the next.

In Iran proper, the first sentence that will be uttered by the next leader of any significant social movement will have to start from the very last sentence of Mir Hossein Mousavi’s magnificent statements and his Manshur/Charter of the Green Movement.

Neither Khatami nor Hashemi is that leader – nor should they try to pull the force of history backwards by falsely arguing that the Green Movement was too radical and they are more moderate.

Is Rouhani bypassing the Reformists and recapping onto the vast ocean of people’s democratic will for the next phase? It is very hard and too early to say, and almost impossible to imagine.

People have cleared the air for him to fly, or else if he prefers the metaphor to change, a warm and inviting sea to swim in – he can pick his metaphor and become part of history.

Hamid Dabashi is the Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York. Among his most recent books are Iran, The Green Movement and the USA: The Fox and the Paradox (2010) and The Arab Spring: The End of Postcolonialism (2012).