‘Education First’ must put the marginalised at the centre

There is a need to draw attention to unacceptable levels of education inequality across countries and between groups.

Goal-setting often leads to attention being paid to low-hanging fruit – those easiest to reach, making it possible to show progress most quickly. Unfortunately, in education, this approach has left 61 million children – many of them poor, girls and those living in remote rural locations – missing out on the push towards getting all children into school by 2015.

It is welcome that one of the three areas being addressed by the UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, in his new global initiative launched on September 26, 2012, “Education First” is putting every child into school.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThirty years waiting for a house: South Africa’s ‘backyard’ dwellers

Photos: Malnutrition threatens future Afghan generations

From prisoner to president in 20 days, Senegal’s Diomaye Faye takes office

To achieve this important intention, future goals and any discussions of a post-2015 agenda must include equity-based targets so that the marginalised benefit from progress. This is a remediable injustice and one which we must all work to resolve.

Ensuring progress in education reaches the marginalised has been a recurrent theme in our Education for All Global Monitoring Report, the next edition of which is due in just over two weeks.

Not only are we aware of the vital role that education plays in counteracting disadvantages over which people have little control, but also its important role in shaping their opportunities for education and wider life chances. But, as time has shown, unequal access to schools can in fact end up reinforcing marginalisation instead.

As part of our campaigning to put pressure on policymakers to counter these disparities, the EFA Global Monitoring Report Team at UNESCO has produced a brand new interactive website called the World Inequality Database on Education (WIDE) available at www.education-inequalities.org.

We designed this to coincide with the launch of “Education First” and the upcoming release of our new report. The website provides data for over 50 countries, allowing you to zoom in on selected countries and indicators, and to compare disparities across countries and identify which groups are most disadvantaged within these countries.

Looking at Cambodia, for example, we can see how, over a decade, the average years of education has increased by more than two years for 17-22 year olds. However, looking beyond the averages, we can also see that the education policies there have not been reaching the poorest. Over those 10 years, the gap between the richest and poorest in the country has remained the same.

Cambodia, 17-22 year olds with fewer than four years in school from 2000 to 2010

Cambodia, 17-22 year olds with fewer than four years in school from 2000 to 2010

Some children or young people may have been disadvantaged by more than one factor in their access to school. In Nepal, for example, WIDE reveals it: while 19 per cent of 17-22 year olds have fewer than four years in school, the percentage rises to 24 per cent for women, 57 per cent for the poorest women and jumps to 75 per cent for the poorest women living in the lowland Terai region. By contrast, only 5 per cent of the richest females in this region had fewer than four years of education.

Nepal, 2011, 17-22 year olds with fewer than four years in school

Nepal, 2011, 17-22 year olds with fewer than four years in school

A key reason for the likely failure to reach the 2015 deadline of the six Education for All goals is because marginalised have not been given enough attention. For this reason, education goals set after 2015 must include equity-based targets.

Take Burundi and Sierra Leone as examples. On the surface, they both have the same average percentage of 17-22 year olds with less than four years of education. However, the gap between the rich and the poor is almost twice as large in Sierra Leone where 72 per cent of the poorest children had spent fewer than four years in school, compared with only 15 per cent of the richest children.

In Burundi, 60 per cent of the poorest had spent fewer than four years in school compared to 25 per cent of the richest.

Burundi and Sierra Leone have the same average percentage of 17-22 year olds with less than four years of education [Unspecified]

Burundi and Sierra Leone have the same average percentage of 17-22 year olds with less than four years of education [Unspecified]

Our EFA Global Monitoring Report shows that statistics matter. Rigorous facts are paramount for persuading policymakers to realise that change is needed. We have seen how our reports and data can help to influence them.

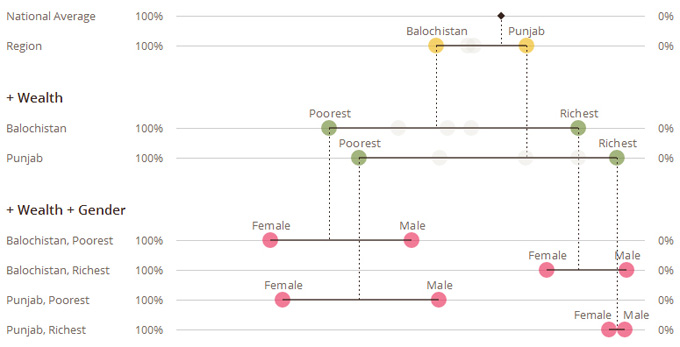

In Pakistan, for example, the data presented in our Report on Reaching the Marginalised heavily influenced the country’s 2011 Education Emergency Report. The report highlighted the gulf between the national average of educational attainment for the poorest in the country, and for those living in the province with the worst educational deprivation – Balochistan. In 2007, 45 per cent suffered from extreme education poverty in the province, compared with 25 per cent in the wealthier province, Punjab.

Yet, vast gender gaps are evident for the poorest in both of these provinces, leaving poor, young women in Punjab with a similar chance of reaching two years of schooling to those in Balochistan: in both provinces, around 80 per cent are in extreme education poverty.

Pakistan, 2007, 17-22 year olds with less than two years in school

Pakistan, 2007, 17-22 year olds with less than two years in school

Our new website is a first step towards drawing attention to the vast disparities affecting millions of children’s chance for an education. However, there is still a need for more and better data to identify the groups that are most deprived of education in different societies. And improving available data for measuring marginalisation in education must remain a high priority for the post-2015 agenda.

For now, our hope is that WIDE will make a visual impact highlighting the extent of disadvantage that policymakers can no longer ignore. Putting “Education First” must mean putting the most marginalised at the centre.

Pauline Rose is the Director of the Global Monitoring Report on Education published by UNESCO.