Dangerous contradictions in Syria

Incoherent national policies and geopolitical rivalries are leading to a worsening crisis in Syria.

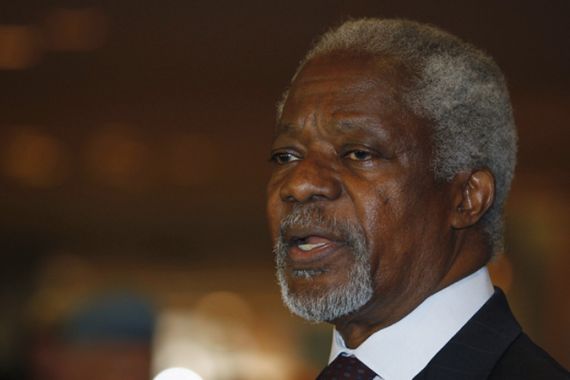

Despite global condemnation of government violence and a UN-brokered peace plan, the crisis in Syria is deepening. The conflict, now labelled a “civil war” by the United Nations Undersecretary for Peacekeeping, is sure to become one, even as relevant powers meet to discuss ways of resurrecting the Annan Plan later in June. The only touchstone for diplomatic efforts surrounding the crisis in Syria, Kofi Annan’s peace plan, is itself in crisis, as up to 2,000 people have been killed in May alone.

The violence in Syria has already spread to Lebanon, which straddles the same communal and confessional fault lines as its larger neighbour, and where the Assad regime’s repression has polarised the population, largely along pre-existing political lines. The Turkish authorities, currently hosting some 30,000 Syrian refugees, are increasingly “disturbed by the possibility that [the conflict] could spread to us”, a concern realised in an airborne attack that downed a Turkish fighter aircraft at the end of June. The coordinated car bombs in Baghdad, Balad, Hillah and Karbala in mid-June, which targeted Shia religious processions and claimed dozens of lives, suggest that instability in Iraq will certainly reflect, as well as contribute to, the escalating violence in Syria.

| Syria in a ‘state of war’ |

A bloody civil war, involving supplies of guns and money from regional and global sponsors, would be disastrous for Syria and for its neighbours. Yet a proxy war has become the default option in an atmosphere of deepening geopolitical rivalries and, more importantly, in the context of incoherent national policies within the region and the wider world alike. Indeed, at the heart of this degenerating situation are webs of inconsistencies that exist in the positions of all the main protagonists in the Syrian crisis.

Syrian inconsistencies

The Assad regime acceded to the Annan plan, the basic premise of which was a ceasefire. In addition to the cessation of armed violence, the plan involved a pullback of troops in and around population centres and an end to the use of heavy weapons there. In reality, the government crackdown has continued virtually unabated. Since the Annan framework came into effect on April 12, there has been large-scale bombardment of civilian areas in many cities, including Idlib, Homs, Raqqa, Hama, Latakia, Aleppo and Rif Dimashq, using tanks, artillery and attack helicopters.

The civilian victims of two alleged massacres in the town of Houla and in the hamlet of Qubair included dozens of children under the age of 10, although who was actually responsible is disputed. While the government denies its forces were involved and it is likely that these killings were committed by loosely affiliated local militias on either side, there are mounting accusations that children, in particular, have been killed and tortured by the regime as a matter of policy.

The government in Damascus is officially committed to a ceasefire and dialogue, and even claims to have organised elections – regarded as spurious by everybody else – but its repression is unending. Indeed, regime violence escalated during the months of April and May (while the Annan plan was in its implementation phase), with Amnesty International extensively documenting torture, arbitrary detention, the burning and looting of homes and widespread and systematic attacks against the civilian population, which amounted to “crimes against humanity”.

|

“For the SNC, a coalition of the main opposition groups, the most problematic incongruity has been between its alleged commitment to democratic principles and some of its practices.“ |

The Syrian opposition grapples with its own inconsistencies. For the Syrian National Council (SNC), a coalition of the main opposition groups, the most problematic incongruity has been between its alleged commitment to democratic principles and some of its practices. The council’s first president, Burhan Ghalioun, was last month forced to step down immediately after commencing his third consecutive term, as critics highlighted the autocratic tendencies of his tenure, the unfair monopolisation of power by the council’s Islamists and the marginalisation in decision-making of other council members.

This episode also brought fresh complaints by grassroots groups that the SNC is disconnected from the opposition inside Syria. The Local Coordination Committees, for example, stated that the SNC was increasingly moving away from the spirit of the revolution and from its goals of a civil state with democracy, transparency and the regular transfer of power. The SNC has also faced accusations of being insufficiently inclusive of minority groups, most notably because it has failed to attract prominent Alawis or Kurdish groups, hence the recent election of a Kurdish activist, Abdelbaset Seida, to replace Ghalioun.

Equally threatening to the democratic orientation of the Syrian opposition is the increasing militarisation of their struggle. While entirely understandable in the face of the regime’s relentless attacks against peaceful demonstrators and then civilian communities, the reality is that it forms a new equation on the ground. At a minimum, it covers and obscures peaceful resistance activity and works to define the struggle as an insurgency, thus challenging the regime at its strongest point. At a maximum, militarisation empowers armed groups with shadowy networks at the expense of civil activists, creating competing leadership and legitimacy claims, as well as increasingly credible claims of their involvement in massacres.

This becomes especially dangerous in a struggle with increasingly sectarian undertones, where groups espousing intolerant, anti-democratic ideologies such as Salafism are in their element. In such a context, the worldview of militant Islamism is reinforced by the notion of force as the final arbiter as well as a millenarian idea of a final sectarian battle pitting the forces of truth against the forces of falsehood. The ascendancy of such groupings within the armed opposition undoubtedly creates an entry point for transnational jihadism, whether from al-Qaeda or from locally formed groups such as al-Nusra, but it also privileges a vision for Syria’s future that is altogether different from that of the opposition in exile and indeed the civil activists who catalysed the protest movement in March 2011.

A related problem arising from the opposition’s course towards full-blown militarisation is the unlawful killings and violations that are incompatible with its charters and democratic mission. In this month alone, Amnesty International documented the torture and killing of captured soldiers and the kidnapping and killing of people suspected of supporting the government, while the UN Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict condemned the recruitment and use of children by armed opposition groups. These abuses, coexisting as they do with covenants describing the primacy of human rights, work to undermine international confidence in the opposition as a credible and just alternative to the current government, which is worthy of all levers of international support.

Western wavering

The western position on Syria is also beset with contradictions that have contributed to the spiralling violence. The stakes in Syria were dramatically raised with the announcement in August last year, first by US President Barack Obama and then by the EU, the UK, Germany, France and Canada, that Assad must “step aside”. At the same time, however, neither the US nor the EU were prepared to act decisively to effect Assad’s removal from power. One Syrian activist described a conversation in which he and some of his colleagues had implored their State Department interlocutors not to demand Assad’s departure because such a policy would, firstly, sever western leverage over the regime and, secondly, lead to a ramping up of the government’s violence owing to its increased desperation.

|

“The US has been aiding the rebels with tactical intelligence, military-grade communications equipment and medical supplies.“ |

In the event, the demand was issued, but with no credible ultimatum. A policy of sanctions was in place – certainly not a short-term solution, given that pledges worth billions of dollars from Iran and Iraq ensured the regime could continue to pay its security forces and access fuel – but the onslaught intensified. In the knowledge that international intervention would not be forthcoming, increasing numbers of Syrians took up arms to defend themselves, while the US and EU watched from the sidelines as the protest movement it sought to protect morphed into an insurgency.

A second tension in the US approach concerns the Annan Plan. As Patrick Seale has argued, “Washington supports the Annan peace plan while at the same time seeking to ensure its failure”. The US has been aiding the rebels with tactical intelligence, military-grade communications equipment and medical supplies. It is difficult to reconcile this support, which has entrenched the opposition’s military position, with the peace plan’s objective of a ceasefire and Syrian-led negotiations. Though probably not providing lethal equipment itself, the State Department is believed to have been coordinating arms consignments to the rebels from the Gulf, particularly from Saudi Arabia and Qatar via Turkey.

That being said, the Russian Foreign Minister on Thursday accused the US of “providing arms to the Syrian opposition which are being used against the Syrian government”. This statement came in response to US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s charge that the Russians had shipped attack helicopters to the Syrian regime. If Clinton’s claim is true, the Russian position is rendered equally incoherent for it, too, claims that it wishes to encourage negotiations, yet, as the recent discovery of a ship off the Scottish coast carrying refurbished helicoptors for Syria has made clear, it too is arming its client in Damascus.

Regional contradictions

Regional players on both sides of the Syrian conflict have also staked out positions that contain marked tensions. Saudi Arabia and Qatar have led the regional and international clamour against the Assad regime’s crackdown as well as calls to arm the opposition. The monarchs of both countries have consistently and uncharacteristically criticised the Assad regime in sharp moral terms.

However, this moral outrage does not sit easily with either government’s policies towards last year’s protests in Bahrain. Although officially dispatched by the six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council in order to guard infrastructure and restore order, Saudi and UAE troops entered Bahrain in March 2011 to militarily quash a growing rebellion by protesters demanding reform there.

The majority of the Bahraini population, and the majority of the protesters, are Shia citizens living under the rule of a Sunni monarchy. In the absence of a cogent explanation by Riyadh for its uneven policy towards the protests in Bahrain and in Syria, a sectarian reality emerges to the fore which Iran has not been slow to criticise. Moreover, this reality intersects with Saudi Arabia’s geopolitical agenda of containing Iran, which is also, incidentally, a staunch ally of the Assad regime and viewed by some Gulf monarchies as the shadow behind the Pearl Monument demonstrations last year.

The Assad regime’s principal local ally, Hezbollah, has taken a similarly problematic stance on the violence in Syria. For years Hezbollah built up its credibility on the Arab street, beyond its social base among the Shia community in Lebanon, by championing the rights of the oppressed. In fact, Hezbollah finds itself in bed with the Assad regime in the first place because of their combined “axis of resistance”, together with Iran, against Israeli imperialism. Nasrallah himself has championed an Arab nationalist narrative built around the notion of solidarity and premised upon inalienable Islamic and human rights. His continued support for the (Shia) Assad regime dramatically undercuts the moral and political foundations of Hezbollah’s ideological framework and dilutes the group’s raison d’etre to its sectarian core. No wonder Hezbollah has dramatically toned down its pro-Syrian rhetoric!

These local, regional and international contradictions combine to create an atmosphere of confusion and deep mistrust. In that context, realist approaches emerge to the fore, slicing through values-based rhetoric to the realpolitik behind it. Throughout the region, the perception of a zero-sum struggle is gaining momentum. With summer and Ramadan upon us, the violence and the death toll is set to increase, as all participants accelerate their ill-conceived and ill-thought-out policies, in the knowledge, as Kofi Annan himself admits, that there is no Plan B to save them from themselves.

Dr Alia Brahimi is a Research Fellow at the London School of Economics.

George Joffe is a Research Fellow at the Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge.