Russia’s election, Kony2012 and online voyeur justice

For a new kind of online propaganda, a massive viewership not only receives the message: it is the message.

St Louis, MO – On March 4, I spent the day watching the Russian election – not the news coverage of the election, but the election itself. Across Russia, 90,000 web cameras were installed in polling stations in order to ensure transparency and ward off allegations of ballot tampering and fraud. Voting was broadcast through the website www.webvybory2012.ru, where viewers around the world could take-in scenes of Russian life: a Chechen man sprawled out on a couch near a makeshift voter booth, a birthday party at a polling station in Tyumen and ballot stuffing in Dagestan.

These videos, while entertaining, were Russian politics as reality TV: a selective spectacle more revealing in what it did not reveal than in what it actually showed. While a few violations were exposed – the Dagestan ballots were eventually tossed – the videos were more notable for what remained blurry (the ballot boxes, in most cases) and for what happened off-screen. Large increases in absentee ballots and supplementary voter rolls, “carousels” of Putin supporters driven to multiple polling stations, and other questionable practices took place beyond the cameras’ watchful eyes.

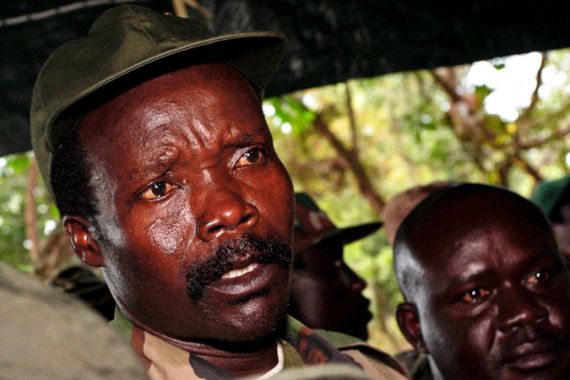

| Viral video focuses debate on Uganda rebels |

By beaming the election over the internet, the Russian government managed to have it both ways: they monitored the voter while obscuring the process. Several foreign observers praised the web cameras for their “transparency”, encouraging Western countries to embrace the same techniques.

Yet the focus on the illusory transparency of a single day distracts from the invisible machinations of the decades-long Putin project. Much like the Western focus on democratic elections can hide an unwillingness to engage with more complex societal reforms, Western emphasis on transparency technologies rewards the documentation of voting at the expense of the complex politics that drive the polls.

Putin is popular in much of Russia and the votes cast were, in many cases, legitimate. And therein lies the problem: live cameras can afford to give the illusion of choice when the choice is a foregone conclusion. The seamy factors that propelled Putin’s inevitability – crackdowns, corruption, censorship – become lost in the livestream.

From Moscow to Kampala

Less than 24 hours after the Russian online election drew to its close, a video was uploaded to YouTube that attempted to shift the dynamics of political intervention. Kony2012, the outrageously popular viral campaign to capture Ugandan war criminal Joseph Kony, succeeded by eschewing any pretense of transparency: its slickness was the source of its success, and of its controversy. The half-hour production has been criticised for falsely representing the conflict in Central Africa, dangerously simplifying a complex narrative and promoting Invisible Children and its representative, Jason Russell, above the Africans they claim to help, in a way many have deemed borderline racist.

As political propaganda, the Kony2012 campaign is the antithesis of the grainy verite vote of the Russian camera stream. It is a Hollywood-style production aimed at snagging Hollywood targets, who will “make Kony famous” by circulating the video, promoting the cause, and, somehow, spurring Kony’s capture. Invisible Children has no shame in developing a campaign around the idea that Justin Bieber carries more diplomatic weight than Ugandan policy advocates, because for its audience – Americans, and judging by its YouTube demographics, many under 17 years old – this is probably true.

Yet the impact of the video has spread far beyond its targeted youth constituency. Viewed by over 65 million people, the video has been praised for stimulating discourse and dismissed for spreading lies, but no one denies that it represents a pivotal moment in the use of online video for activism. Justice, in the Kony2012 paradigm, stems from visibility: “If people knew who he was, he would have been stopped long ago,” the video’s narrator claims.

By this logic, Kony2012 becomes exponentially more noble with each click – much like in the Russian election, when the presence of hundreds of thousands of informal election “monitors” watching from home were said to increase fairness with every view. And like the Russians who fervently embrace Putin, Invisible Children’s acolytes are sincere in their devotion to their cause. The behind-the-scenes politics may be dubious, but the crowd came out on its own, and then watched itself doing so. In both cases, deceptive politics are given click-through credibility, validated by the sheer number of witnesses.

That Kony2012 appeared the day after Webvybory2012 is coincidental, but their use of online video shares an important similarity. They are examples of online voyeur justice, in which a cause (electoral transparency, conflict resolution) is made meaningful only through viewership on a massive scale: unless “everyone” knows, unless “everyone” can see, both the video and its allied cause lose validity.

A video does not need to have mass circulation to be meaningful: Syria’s Shaam News Network, for example, is chock-full of irreplaceable videos of war crimes with viewer numbers in the single digits. But for both the Russian election and Kony2012, scale determines meaning. If Kony2012 does not circulate enough to make Kony famous, then it has, even by its own standards, failed. If the Russian election isn’t broadcast en masse, then its claims to transparency – which do not extend outside the online realm – collapse.

In their ideology and motivation, the two cases may seem disparate, even opposite. The Russian web camera election was the product of a controlling state trying to make itself seem transparent and natural; Kony2012 was the product of idealistic youth trying to make a chaotic conflict seem easy to control. But they are part of a new kind of online propaganda in which a massive viewership not only receives the message, it is the message. That the message is framed in a way that is entertaining, emotional, and “real” only masks the complex and corrupt politics that lie behind it – and heightens its popular appeal.

Sarah Kendzior is an anthropologist at Washington University in St Louis who studies politics and digital media.

Follow her on Twitter: @SarahKendzior