The Invisible Arab: Excerpt from Chapter 1

Read an excerpt from Chapter 1 – L’Ancien Regime – of Marwan Bishara’s latest book, The Invisible Arab.

|

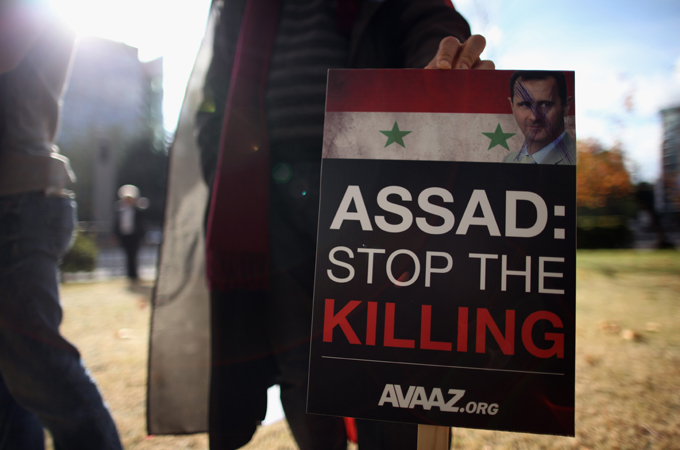

| Arab regimes depended mainly on force for their survival [GALLO/GETTY] |

The following is the second of a series of excerpts that Al Jazeera will be publishing from The Invisible Arab: The promise and peril of the Arab revolutions. The excerpt from the preface can be found here.

What went so wrong? How did the dream of liberation from colonialism turn into a nightmare for Arab states of north and northeast Africa and the Middle East? How did sovereignty designed to keep the West out turn into an alibi for keeping the people down? How did self-declared political leaders become national criminals? Why did they last so long and become so brutal, frequently even more so than their colonial predecessors?

In tracing the ills of the modern Arab world, some pundits have highlighted religion as the main source of its “backwardness”, while others have underlined Arab cultural deficiencies that prevented the region from embracing rational policies and democratic principles – a mindset known as cultural exceptionalism, or its latest media term, “the caged Arab mind”. But it’s not within the scope of this essay to expose these and other fallacies about an intrinsic Arab backwardness, or analyze racist views of Arabs and Islam.

What is important to remember is that the Islamic world counts for some of the world’s most economically successful and democratic nations, and to recall the great historical periods in Arab civilisation, including the period when Arabs documented, translated, and revived interest in the achievements of the classical world, while Europe was mired in the dark ages. It’s also important to remember that full universal suffrage was adopted by the West as late as the twentieth century, with most other countries implementing it only over the last few decades, and recognise how Arabs have embraced the idea of elections whenever possible, even under military occupation, as in the case of recent Iraqi and Palestinian elections, where citizens voted with little hesitation in the hope that their ballots would count.

It’s my contention that the roots of Arab problems are not civilisational, economic, philosophical, or theological per se, even if religion, development, and culture have had great influence on the Arab reality. The origins of the miserable Arab reality are political par excellence. Like capital to capitalism, or individualism to liberalism, the use and misuse of political power has been the factor that defines the contemporary Arab state. Arab regimes have subjugated or transformed all facets of Arab society.

Since gaining liberation from Western colonialism, the Arab world has been ruled mostly but not entirely by regimes whose practice has been antithetical to any sense human progress, unity, democracy, and human rights. Those who tried, albeit selectively to chart a better way forward on the basis of national security and national interest, were dissuaded through pressure, boycotted, or defeated on the battlefield. The political backwardness of the larger postcolonial transformation soon became the plague that infected everything else. The guardians of the state who were entrusted with the welfare of their nations monopolised power, controlled the economy, and ignored the civil liberties of the majority in order to privilege the few.

That is why twenty-first-century Arab revolutionaries need to go beyond changing leadership and actually reinvent state structures if they want to transform Arab society.

Totalitarian and authoritarian (You say tomato, I say tomahto)

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, Arab autocracies represented some of the oldest dictatorships in the world. Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s dictatorship in Tunisia, the most recently established in the region, ruled for twenty-five years, followed by thirty years for Egypt’s Muhammad Hosni Sayyid Mubarak, thirty-three years for Yemen’s Ali Abdullah Saleh, forty-three years for Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, and forty-three years for Syria’s Bashar al-Assad dynasty. Saddam Hussein was removed in 2003 after twenty-four bloody years ruling Iraq. Only the Arab authoritarian monarchies precede these dictatorships in longevity. Bahrain, a repressive Sunni monarchy, has ruled over a Shia majority since its independence from Britain in 1971.

Arab regimes have differed in the degree of control and violence they have exercised – from relatively open authoritarian regimes to terribly closed totalitarian autocrats. The former allowed for limited diversity, semi-political organisation, and tempered freedom of expression, but didn’t allow for change of governments or power-sharing through free and fair elections. So, for example, Egypt allowed parties to compete in parliamentary elections but set strict criteria for the eligibility of candidates and voters, ensuring that the results favoured the ruling party whose leader remained president through phony referenda. And in the monarchies of Morocco, Jordan, Kuwait, and Bahrain, parliamentary elections were held, paving the way for certain degrees of representation in parliament, and, at times, an elected government. Alas, these parliaments were curtailed or summarily dismissed by royal decree. The fact that some of these authoritarian regimes didn’t try to define, micromanage, or determine every aspect of their societies made them more tolerable for the average citizen.

Despite Mubarak’s and Ben Ali’s authoritarian regimes and their hold on their countries’ institutions and military, state and society were kept relatively separate from the regime, just as loyalties to regime and state were kept separate. In comparison to their Arab peers, Egypt and Tunisia have had strong middle and working classes, durable national institutions, and a cohesive modern identity within a long-established nation-state backed by thousands of years of collectively shared history. Tunisia has one of the highest rates of literacy in the Arab world and has had a modern constitution since 1861, two decades before the French colonised it. Gender equality was established in the mid-1950s, long before other Arab and European women enjoyed the same rights and privileges.

Egypt, with five thousand years of civilisation along the Nile, is even more steeped in history. The nation sits on strong institutions that were developed during the nineteenth century, after Mohammad Ali took over in 1805 and began to modernise the country and its main metropolis. It’s this cohesiveness, strong national identity, and culture that have been missing from the other Arab states swept by the Arab revolt.

More totalitarian Arab regimes, on the other hand, have aimed to erase features of plurality and diversity in order to establish a uniform political society based on the ruling ideology. Exercising direct censorship over the media, they monopolised political thought and all aspects of civil and political society. In Syria and Iraq, the Baath party monopolised government, the economy, and the armed forces, and enshrined its singular control of government in the constitution, not allowing for alternation of power.

The totalitarian regimes couldn’t be distinguished from their militaries and, to a large degree, the national institutions. Little space was left between the naked force of the clan-based regime and the defenseless citizens, as various protective state agents and mediators – whether legal, civic, or welfare-related – were scrapped, definanced or simply ignored.

The lines between state and regime were blurred, as were the buffers between regime and family, security, military, civic, and religious institutions. The neutrality and independence of national institutions, such as judiciary and parliament, were totally compromised. States were, for a lack of better words, turned into the private estates of the ruling families. While these regimes boasted of secular republicanism, they were run similar to the Wahhabite kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, where no political activism was allowed and where the ruling families dominated all facets of political life.

Totalitarian regimes justified their total monopoly of power on the basis of holistic ideologies and bombastic visions, deceptive or unrealistic as they might be. The Syrian constitution’s Article 8 makes it clear that only the Baath party can govern the country. In Libya, the leader of the republic who referred to himself as the “king of kings”, dismantled all political parties and instated his rather ludicrous The Green Book as the country’s de facto constitution or bill of rights. The more ostentatious the cult of personality, the more secretive the mechanisation of their security services became.

It’s as if the greater-than-life statues of esteemed leaders and regime symbols were meant to replace the people who were ejected from the public space altogether. Similarly, the welfare state was removed from communities at large.

These are the factors at play in countries like Syria and Libya, where falling leaders threaten to take their countries down with them, unlike the authoritarian regimes in Tunisia and Egypt, which seemed to crumble with the downfall of their leaders. For decades, totalitarian rulers exploited all resources and facets of their nations to consolidate power and authority, rendering their regime indistinguishable from the state. For them, the fall of the regime could mean no less than the end of the state.

The totalitarian Arab republics have deteriorated into Mafiosi-type rule. Their motto: (brother) leader first, country second, and people third, or as they said in Libya, “Allah, Moa’mar, Libya”. In one of the most disgusting scenes, which occurred in mid-2011, Syrian security thugs tied a middle-aged man’s hands behind his back, slapped him, and demanded he repeat after them, “There is no god but Bashar”!

Arab regimes depended mainly on force for their survival. The names and responsibilities of their security organisations under the direct control of the inner circle of the regime varied from one country to another, but the principle remained the same: Servicing and defending the regime at any cost. And from the way these security services responded in Libya, Yemen, and Syria, they also risk plunging their respective country into civil war. The first priority of internal security, state security, security services, intelligence services or their military counterparts, the Republican Guards, Presidential Guards, and special units – not so dissimilar from Royal Guards in Saudi Arabia – was to prevent a coup against the regime.

Preventing a coup is achieved by placing these special units on top of all national military services, police, and other state institutions – all of which explains why, since the 1987 takeover by Ben Ali, no regime change has taken place in the Arab world. Before the 1980s, though, the Arab world witnessed many coup d’états. Of course, in the monarchies, such as those in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, royal family members were in control of the military.

For decades, Arab autocrats cited foreign and international threats to justify their resistance to reform; that included the constant state of war in the region, involving notably Israel, Iran, and the United States, especially in the post-Cold War period. Domestically, Arab leaders justified their tight grip over state power on the basis of defence against Islamic fundamentalism and ethnic secession and conflict. But as these leaders grew more confident and arrogant, they no longer bothered to explain why they continued to rule people “until death sets them apart”. Indeed, the Arab world knows no former Arab leaders, only dead ones.

This was best articulated by an army officer in the southern Yemeni city of Taiz, where Republican Guards attacked protestors in Horriyah (Liberty) Square using water cannons, bulldozers, and live ammunition, killing at least twenty of peaceful Yemenis in the process. In response to the protesters’ slogan “the people want to bring down the regime”, the officer brazenly wrote on a wall: “The regime wants to bring down the people”.

Marwan Bishara is Al Jazeera’s senior political analyst and a former professor of international relations at the American University of Paris.The above excerpt is from his latest book, The Invisible Arab: The promise and peril of the Arab revolutions, out in bookstores now.

Follow him on Twitter: @MarwanBishara