Mitt Romney, ‘welfare queen’

Romney’s wealth is based on the private equity business model, founded on tax-payer subsidies.

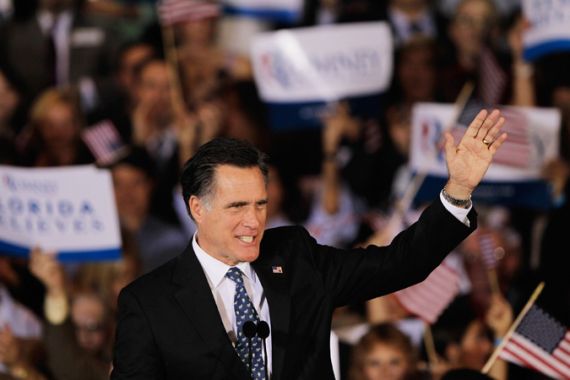

|

| Mitt Romney’s limited tax-form release validates what we already knew: He’s not just a member of the one per cent, he’s in the one per cent of the one per cent, says Rosenberg [GALLO/GETTY] |

San Pedro, CA – Ever since Brown vs Board of Education, conservatives have been complaining about judges “legislating from the bench”. It was a brilliant strategy: “We’re not racists,” they could say. “There’s a matter of high principle involved here.” But it was not until 56 years later, with the Citizens United decision – and conservative justices ruling the roost – that we got to see what an earth-shattering example of legislating from the bench really looks like – and the Republican presidential primary is the number one surprise casualty. It’s just the sort of unintended consequence you’d expect in the absence of a thorough legislative fact-finding process, and the fine-tuning of final legislation. It’s not that the legislative process is flawless – far from it. But this sort of staggering bolt-from-the-blue consequence is precisely the sort of thing that the legislative process is intended to avoid, and that the judicial process is ill-equipped to anticipate. Oops!

So now the GOP has gotten a taste of their own medicine, with lurid, hyperbolic attack adds dominating the electoral process. And they do not like it, not one bit. Two deeply flawed candidates have emerged as frontrunners in a process that has exacerbated and amplified those flaws a thousand fold. The tide may have finally turned, Mitt Romney may have finally learned how to punch back, and the tide of establishment money may have finally swamped Newt Gingrich for good as a serious threat – though he’s unlikely to quit. But even if Gingrich were to quit today, months and months of videotaped debates, press conferences, attack ads and various other vicious odds and ends are not just going to go away. They’ll be back when the general election campaign really heats up next fall.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsChina’s economy beats expectations, growing 5.3 percent in first quarter

Inside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

Manipur’s BJP CM inflamed conflict: Assam Rifles report on India violence

|

|

More importantly, the Republican primary has unwittingly validated the Occupy movement in spades, laying the groundwork for a potentially very different sort of campaign environment not just in the fall, but starting right now. Mitt Romney’s limited tax-form release validates what we already knew: He’s not just a member of the one per cent, he’s in the one per cent of the one per cent – perfectly positioned to illustrate everything that’s wrong with the existing system. Seen through the lens of Romney’s own example, it’s not capitalism per se that’s the problem, but the dramatic shift away from a form of capitalism that benefited almost everyone to a form that only benefits a small handful. And it is Gingrich’s campaign that has forcefully made this point, on the stump, in debates and in the half-hour video, When Mitt Romney Came to Town, which starts off with a paen to capitalism as the source of the strength of the US, before turning dark with its focus on Wall Street, leveraged buyouts and Romney’s Bain Capital in particular.

Although Gingrich attacks Romney for what he’s done to US workers, there’s an even deeper jujitsu criticism to be made of his business mode: Mitt Romney is a welfare queen. As we’ll see below, without the tax-breaks given to interest payment, the private equity business model would never have been born. Those tax-breaks are nothing but a taxpayer subsidy, paid for by everybody else picking up the slack for Mitt Romney and his crony corporate raiders. But let’s not spoil our appetites by starting with dessert.

Newt’s populist put-on

Economist Dean Baker is one of a small handful of economists who saw the housing bubble for what it was years before its inevitable bust. In the 1990s, he began what might be the first blog, Beat The Press, devoted to debunking false assumptions and misleading arguments in the economics coverage of the Washington Post and the New York Times (later expanded to include to the Wall Street Journal and the Economist). His most recent book, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive, argues that the right/left divide on economics should not be conceived of as pro- vs anti-free market, but as how to structure markets – to favour the rich, or to favour society as a whole.

Baker’s prescience, breadth of vision, and detailed critical attention to the foibles of economic conventional wisdom made him an obvious choice to turn to with questions about what all this might mean. Before turning to Romney, I asked him first about Gingrich’s populist rhetoric, and how Obama’s policies had opened the door for this implausible development. I talked to him just before Gingrich’s sharp decline in Florida’s polls.

“Gingrich is really an astute politician,” Baker began. “In principle, he’s very much of these elites. He made millions of dollars as a lobbying, we know what he did. He very much comes from that group – so him going against the elites is a little perverse that way, but that doesn’t mean he couldn’t do it. Would he be able to win? I wouldn’t rule it out. President Obama has gotten more populist in his rhetoric in the past four or five months. But it’s not clear that it’s going to translate much into action. More importantly, for him in terms of election, it’s not clear that people will buy it.”

As for how Obama’s policies opened the door for this, Baker first pointed to the undersized stimulus, and referred to the just-released “Summers Memo“, defining the framework of Obama administration, thinking about the stimulus before taking office. “He was always very cautious about the stimulus,” Baker said. “They under-estimated the severity of the downturn and they were always concerned that they go too far with the deficit, and clearly that was the wrong approach. They needed much more stimulus than they got.”

“The result of that is we got very weak recovery. You know, the unemployment rate is still very high. That’s what people are going to grade him on. So, to some extent, his line is ‘it could have been worse’. Of course, that is always true. It’s not a very compelling re-election slogan.”

Baker also pointed to the failure to break up the big banks. “The banking system is more concentrated [now] than it was before the downturn,” he pointed out.

|

|

But one reason I chose Baker was because I knew he’d thought a lot about other things that could be done. And he did not disappoint. He turned to the disaster of Obama’s foreclosure programme (HAMP), but wasted no time criticising it, instead turning quickly to what could have been done. “What I would have preferred, I argued for this, was the right to rent – allowing people to stay in their homes as renters, following foreclosures so that would lead to housing security, and probably lead to lots of banks voluntarily doing write-downs in order to avoid that situation.”

It would also have meant a lot fewer houses standing empty, helping to drive down property values for the neighbourhoods around them. “In the same vein,” Baker continued, “he could have pushed for bankruptcy cramdown, which again does the same sort of thing. It gives people a stick in their negotiations with banks. He basically backed down on that. He may not have been able to get that through Congress, but he didn’t try.”

“So he did all these things that people question, they don’t necessarily know all the details, but they can see the banks are still there, bigger than ever and people without work are losing their homes. So, without knowing a great deal about specific policies, it’s not hard for people to draw the conclusion he doesn’t really seem to be on our side.”

This helped create the perfect opening for a huckster like Gingrich. And though his candidacy may be fading, his impact lives on – particularly when it comes to reframing Romney, not as a poster-boy for capitalism, but as a cautionary example of how it has gone wrong these past 30+ years.

Private equity 101

Baker cited two different issues that have been raised about private equity firms. First is the casual indifference to workers, treating them as utterly disposable. Second is the way the tax codes actively create incentives for them, without any countervailing laws, policies and practices to curb their destructive effects. The first, Baker noted, had been emphasised by Gingrich’s video, When Mitt Romney Came to Town.

“You have all these people who have worked for decades, and now they throw them out the door and give them nothing. It’s not something only private equity companies do. Now private equity companies do that, but General Electric does it, General Motors … downsizing is not unique to private equity,” Baker pointed out. “It would be great to get a discussion going. Clearly that has resonance. That’s one of the things I love about this. Here’s Newt Gingrich doing this in a conservative Republican state. And he’s not stupid, I’m sure he had this focus-group tested and he did this because he know this would have resonance.”

It could easily be quite different. “The US really stands out that way. Across Europe, just about everywhere you can’t just fire someone who’s been working for you for years. You owe them severance pay, you at least have to give them warning.” Policies that pay, say, two weeks of severance pay for every year of employment, provide both a cushion for workers who are fired, and a disincentive to casually fire them in the first place. In the US, Baker noted, “CEOs get that, so it’s not a concept that’s not known here”.

From the standpoint of basic economics, Baker said, “We know there’s externalities in the sense that you lay off a worker in their early 50s, they have a hell of a time getting re-employed. Many never will. So they’re going to collect unemployment benefits, in addition to the harm it does to the worker, so it’s reasonable to say there are serious externalities here. If someone’s really not pulling their weight and you’re paying them, fine, get rid of them, but give them something to go away on. And if that prevents you from doing it, well then, maybe they’re not that much of a drag.”

This much is relatively easy to grasp – as proved by Gingrich’s stunning upset in South Carolina. But the second issue – the role of rigged rules, including the tax code – may be harder to grasp or even just focus on… or at least it was, before Romney released his tax returns, turning himself into a poster-boy for the nexus between high incomes and low taxes.

|

| Absurd accusations of Obama being a ‘socialist’ may be bolstered by racial stereotypes [GALLO/GETTY] |

Private equity for grad students

“The basic story of private equity [called “leveraged buyouts” in the 1980s] is that they leverage firms to the hilt and then they hope that they have something viable to sell off at the end of the day. But very often, they’ve already gotten their money out either way,” Baker explained. This is quite different from venture capital – the funding of small startups that pour resources into a company, rather than stripping them out – which Bain originally focused on, but largely abandoned for the less risky, more lucrative private equity game.

“It’s standard practice that they buy a firm, they borrow against the firm, so it’s not their own borrowing… then they pay themselves back from the borrowing.” This is the key: the company bought pays back the buyer, even while taking on debt itself. (And the key to the key is that debt payments are tax-deductible.) But then it gets worse, Baker said, “Then they sell off assets, so they sell off their real estate, and they often set up a REIT (Real Estate Investment Trust) and that will hold the real estate and then they rent it back to the stores. So here, they have these stores, they have been a viable, profitable company, now they have all this debt, plus they don’t have any assets. They have to come up with the rent each month to stay in business.”

“At the end of that, if they still have a company they can sell off, they’re golden. If they don’t, well, they just go into bankruptcy, and they tell the creditors: ‘Hey, too bad, you’re out of luck.’ And if they’ve already gotten their money out, the private equity company’s OK. So what they manage to do is create a heavily leveraged bet where they pretty much could only win. It’s a one-sided bet.” Which is why Bain found it so much more attractive than the venture capital game. Indeed, it’s so attractive that private equity firms frequently buy and sell companies back and forth to one another, making money with each transaction underwritten by taxpayers. Brand-name companies, with decades, even a century or more of public goodwill, have been taken into bankruptcy, then purchased by another private equity firm multiple times.

As already indicated, there’s a huge political/tax policy point to all this, Baker explains. “A lot of what’s going on is that interest is tax-deductible, whereas dividends are not. So a lot of their gains are simply replacing dividend payments with interest payments. Which comes from the taxpayers. You’re not creating value. Mitt Romney – if he loads up a company with debt – he hasn’t created value, he’s just basically found a way to bilk the taxpayers. You can get rich, but that’s not creating value for the economy.” That’s the initial stage, the tax law that gets the ball rolling. The second stage, the asset stripping, which frequently leads to bankruptcies, involves ripping off creditors. “There, too, it’s not a case where you’re creating value. You’re basically creating risk for other people, getting rich in the process.”

Conceptually, it’s not hard to fix this situation. “You could get rid of the tax reduction for interest, or in any case make interest payments and dividend payments symmetrical.” That alone might well do the trick, since the tax savings are key to making leveraged buyout deals possible in the first place. But making the law more creditor friendly to protect against asset-stripping should also be considered, Baker said.

Financial journalist Josh Kosman wrote a whole book on the topic, The Buyout of America: How Private Equity Is Destroying Jobs and Killing the American Economy. In an interview at Mike Konczal’s Rortybomb blog, he explained both how things got started, and how they changed.

“The original leveraged buyout firms saw that there were no laws against companies taking out loans to finance their own sales, like a mortgage,” Kosman said. “So when a private equity firm buys a company and puts 20 per cent down, and the company puts down 80 per cent, the company is responsible for repaying that.”

Those who began this practice differed significantly from those who never knew anything else. At first, the leveraged deal was just part of a process, most of which was not that different from standard business practices. But this soon changed, simply because the leveraging process was profitable. It became common practice to use short-term profits to take on more debt, while paying dividends to the private equity firm.

|

|

“If you look at the dividends stuff that private equity firms do, and Bain is one of the worst offenders, if you increase the short-term earnings of a company, you then use those new earnings to borrow more money,” Kosman said. “That money goes right back to the private equity firm in dividends, making it quite a quick profit. More importantly, most companies can’t handle that debt load twice. Just as they are in a position to reduce debt, they are getting hit with maximum leverage again. It’s very hard for companies to take that hit twice.”

This departed significantly from the original model, Kosman explained, “If you look at Ted Forstmann, an original private equity person who just passed away, he would rail against dividends in this manner – borrowing money to pay out dividends. He was more interested in taking companies public and selling shares and paying down debts and collecting proceeds that way. I can respect that a lot more. The initial private equity model was that you would make money by reselling your company or taking it public, not by levering it a second time.”

The backdrop to all this is the taxpayer subsidy. As Konczal noted, “A recent paper from the University of Chicago looking at private equity found ‘a reasonable estimate of the value of lower taxes due to increased leverage for the 1980s might be ten to 20 per cent of firm value’, which is value that comes from taxpayers to private equity as a result of the tax code.”

And Kosman pointed out that for the 1990s, “Moody’s just put out a report in December that looked at the 40 largest buyouts of this era and showed that their revenue was growing at four per cent since their buyout, while comparable companies were growing at 14 per cent”.

With two or more rounds of leveraging, taxpayer subsidies, and much lower growth rates, the private equity model has little, if anything, to recommend it to society at large. But Romney, who started at Bain as CEO in 1984, never knew any other way of doing business. Except, that is, for the relatively brief period of time when Bain focused on venture capital deals, deals that actually can and do build companies and add jobs – though often at the expense of other companies and the jobs they provided (just think of how many independent stationary and office-supply stores Staples helped to put out of business, for example). The fact that Romney shifted focus from venture capital to private equity tells you everything you need to know about what his priorities were. “Creating jobs” was clearly not among them. Nor was creating lasting value. That’s simply not what the private equity world is all about. And that world reflects the values that have come to define the one per cent, increasingly at odds with the welfare of the US as a whole.

Obama-Romney campaign

While most Democrats would love nothing more than to run against Gingrich this year – polls indicate he could lead the GOP to a landslide defeat, taking down thousands of other elected officials as well -Baker leans the other way. “In a lot of ways I’d prefer to see a race with Romney,” he said. “Of course, Obama will run the kind of race he wants to run… But it’s more likely to pressure [him] to run a campaign that might actually focus on some fundamental issues of what the economy might look like. I worry that if you had a race with Gingrich it might get buried under complete nonsense.”

|

|

There would also be a more favourable environment for progressive economic ideas to be advanced. “The battle over SOPA [the “Stop Online Piracy Act”] is fascinating,” Baker said, citing a recent example. There had been a prolonged battle waged by online activists, fearing it would cripple the web as we know it. But as soon as Google and Facebook got on board against it, a flurry of about-faces occurred – both in the Senate and the White House.

“When people with money – people with power – are getting burned, that’s when you can make change,” Baker said. The getting burned part has certainly been happening with creditors left holding the bag in private equity bankruptcies. A Romney candidacy just might provide an organising opportunity for them to fight back – and in doing so, to make things better and fairer for the rest of the US as well.

Ever since the Great Depression, Republicans have attacked Democrats as being anti-business, anti-capitalist, “creeping socialists”, “soft on communism”… the attacks on Obama as a socialist, among other things, are particularly hyperbolic and absurd, bolstered by racial stereotypes and animosities, but they come out of a long tradition. Yet, the historical record is clear: the US as a whole has done best under Democratic rule. From the end of World War II through the early 1970s, when even Richard Nixon said: “We are all Keynesians now,” the rate of income growth for all levels was relatively well in sync. From 1945 to 1973, incomes rose 99 per cent for the bottom 99 per cent, but only 40 per cent for the top one per cent.

But from Reagan’s election in 1980 through to 2007, the year before the Wall Street crash, the top one per cent gained 232 per cent, compared with just 20 per cent for the bottom 99 per cent. The record of government budgets is equally clear-cut. Every presidential term from the end of World War II through the early 1970s also saw a reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio – the most basic baseline measure of fiscal responsibility. Every presidential term from 1980 onwards has shown a significant growth in the debt-to-GDP ratio… except, of course, for Bill Clinton’s two terms. (A trajectory that began two years before Gingrich became Speaker.)

As long as Republican’s black-and-white rhetoric shapes economic debates, the vast majority of US voters will continue to be bamboozled into a more and more dysfunctional state, reflected in the most basic economic data referred to above. This bamboozlement has been going on for three decades now. But if the focus shifts to particular practices, if it’s a question of how markets are structured and why, a commonsense, nuts-and-bolts question of who benefits and who loses, then things could be very different.

The economist, Hyman Minsky, whose financial instability hypothesis predicted and explained the genesis of the Wall Street meltdown decades in advance, had a much more refined, historical understanding of capitalism as an evolving real-world system, rather than an ideological construct. In a co-authored 1996 working paper, “Economic Insecurity and the Institutional Prerequisites for Successful Capitalism“, he wrote:

The financial structure of the American economy has undergone significant evolution over the history of the republic. From its initial stage of “commercial” capitalism, during which external finance was used mainly for trade, this structure has evolved into its present stage of “money-manager” capitalism, where financial markets and arrangements are dominated by managers of funds.

Two financial stages, “industrial” capitalism and “paternalistic” capitalism, were dominant between the eras of commercial and money-manager capitalism.

Against this broader historical background, the question raised by private equity firms such as Bain Capital is whether they’re a feature or a bug of money-market capitalism – as well as what other buggy features we might well want to alter or abolish, as our founding fathers might have put it. This is a very far cry from being a “socialist attack” on the American way of life.

If the issue is not capitalism in the airy abstract, but the concrete historical reality of Bain Capital and the world it represents, then maybe, just maybe, we really might start inching in the direction of real and fundamental change. Change we don’t have to believe in, because we can shape it with our very own hands and see it with our very own eyes.

Paul Rosenberg is the senior editor of Random Lengths News, a bi-weekly alternative community newspaper.

Follow him on Twitter: @PaulHRosenberg

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.