The shape of African American geopolitics

The Cold War era brought landmark gains in civil rights at the price of stunting black critique of foreign policy.

Palo Alto, CA – In the years following the Second World War, when the United States emerges as a superpower and beacon of democratic freedom, US officials began to propagate the idea of domestic racial progress – the nation’s Achilles’ Heel – to a sceptical global audience. This strategy afforded extraordinary opportunities for black writers and artists, and ushered in political gains for African Americans and other minorities – but these gains were exacted at a steep price.

Examples abound. In 1950, amid desegregation initiatives in the military (1947) and in education (1954), Dean Acheson’s State Department asked black writer J Saunders Redding to represent America on an extended tour of India – whose citizens were closely following civil rights developments in the US – in the wake of that nation’s partitioning and emergence from British rule, a watershed that black Americans reciprocally engaged. In the sphere of international relations, African American diplomat Ralph Bunche wielded tremendous influence on post-war foreign policy, brokering a difficult 1949 armistice between the state of Israel and Lebanon, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan that earned him a Nobel Peace Prize in 1950.

In 1956 president Eisenhower and the State Department funded black and white jazz musicians on tours of Africa, Europe, and the Middle East as part of an effort to project images of black social advancement and interracial collaboration, thereby countering (if not negating) Soviet propaganda of America as a racist empire. But these delegations – symbols of a triumphant American democracy – took flight when the US was still a Jim Crow nation.

In fact, the tours foregrounded the unprecedented significance of African American culture during the early Cold War, a period coinciding with the US Civil Rights movement and the global anticolonial struggle.

Shifting geopolitics

Historians disagree about the precise role that the Cold War played on the Civil Rights movement, but it’s clear that the confluence of these moments – which produced landmark gains in some areas (voting, education, public accommodations), and strictures in others (criticism of economic inequality, anticommunism, or colonialist adventurism) – shifted the terrain of black geopolitics. Ever aware of competing communist attempts to attract the Third World, government officials coupled public diplomacy with efforts to silence or discredit black intellectuals who criticised American and western foreign policy.

This dynamic is easy to see in light of African American approaches to international politics during the 1930s and 1940s. Those decades witnessed a rising internationalist and anticolonial consciousness among African Americans. The Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 galvanised unprecedented numbers of African Americans and other blacks in the diaspora, especially Jamaicans and Trinidadians, in support of the continent’s only independent country – a country long idealised in the pan-African imaginary. Activists and sympathisers raised funds, organised pro-Ethiopia councils, petitioned the League of Nations, offered moral support, lent technical expertise, published articles condemning colonial fascism, and tried in the face of government strictures to enlist in the Ethiopian military. Conducted with an unmistakable sense of urgency, this response to Mussolini’s occupation constitutes one of the earliest, and most heroically conceived, new world challenges to European fascism.

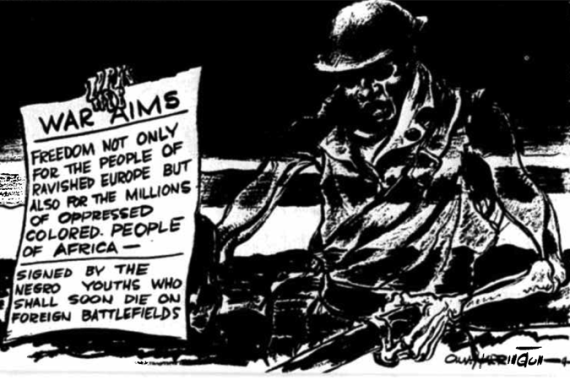

With the onset of the Second World War, African American newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier and the Chicago Defender dramatically grew in circulation and prestige in large measure because of their war coverage and analyses. The black press presented various positions on the war but tended to adopt a non-interventionist policy – surprisingly perhaps given the noxiousness of Nazism and its grave implications for minorities and “the darker peoples”.

Yet acidic memories of the First World War – when black interventionists believed that their support would redound to African American citizenship after the war, it instead sparked racial pogroms – left many disillusioned and inquisitive about the true meaning of the war. Many wondered: Was the war really a battle between the free world and the slave world, between the ideologies of totalitarianism and democracy? Or was it actually just another devastating competition for the spoils of empire?

Disparate factors – a reckoning with the destruction of European Jewry, the bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941, and intimations of racial equality on the horizon – prompted American and transatlantic blacks, increasingly, to support the war, but this time around with a determination to defeat colonialism and Jim Crow along with fascism.

Analogising the Jim Crow and Nazi regimes, writers in the black press ridiculed Allied rhetoric about the war effort and underscored the hypocrisy of western pronouncements about freedom. Relentlessly, intellectuals like George Padmore and W E B Du Bois linked African American strivings with anticolonial struggles worldwide.

Inhibiting critique of foreign policy

Unlike the First World War, the aftermath of the second did seem to signal the retreat of Jim Crow, but this also inhibited black critiques of foreign policy.

The case of Walter White, secretary of the NAACP – the nation’s most prominent Civil Rights organisation – is a prime example. In the 1940s, White broadened his perspective on race and adopted an anticolonial stance. “World War II”, he wrote in 1945, “has given to the Negro a sense of kinship with other coloured – and oppressed – peoples of the world…he senses that the struggle of the Negro in the United States is part and parcel of the struggle against imperialism and exploitation in India, China, Burma, Africa, the Philippines, Malaya, the West Indies, and South America”. White indicted plans by the European colonial powers to restore their empires in Asia, while imploring US officials to commit to a world without colonialism.

White’s ability to mediate white and black constituencies enhanced the effectiveness and stature of the NAACP. In the 1930s, for instance, his anti-lynching advocacy earned growing support from Congress and the public; on the 1940s cultural front, White lobbied Hollywood executives concerning portrayals of blacks in films.

His foray into foreign policy met different results. Like many post-war activists, he viewed the fledgling United Nations as an auspicious forum for addressing civil rights. In 1947, Du Bois drafted An Appeal to the World, a case for human rights violations against the Negro, for presentation in the UN General Assembly. White supported the appeal but he and Du Bois disagreed sharply about whether to collaborate with state actors in order to achieve this aim. Du Bois seemed to think that collaboration was useless; White believed that it was possible and indeed necessary.

Eventually, the director of the UN Division of Human Rights received White, Du Bois, and others for a publicised presentation of the Appeal. Further tensions delayed the publication of the text, however, and exacerbated the confrontation between White and Du Bois.

Rather overconfident about his own influence, White sought to leverage his contacts and sway top officials on matters of race and colonialism. But instead, state officials began to exert pressure on him, and conformity became the price of access to the government’s elite.

When White appeared to renege on that price, officials tried to silence him. He circulated a memorandum among fellow attendees of the General Assembly that contained information culled from allegedly off-the-record meetings of the U.S. delegation. The memo criticised what looked like American acquiescence in the post-war distribution of Italy’s former colonies Eritrea and Libya among Italy, Britain, and Ethiopia. Consequently, a prominent member of the American delegation, Chester Williams, censured White for “serious infringements of confidence”, confiscated remaining copies of the memorandum, and sought to terminate White’s access to confidential meetings.

Williams and White eventually made amends. But as historian Kenneth R Janken has noted, “White would cease public criticism of American foreign policy… thus allowing him to continue to attend the off-the-record briefings. He must have thought that his concessions were part of a quid pro quo.”

Did White genuinely change his views on U.S. foreign policy and domestic racial progress, or did he capitulate to government pressure to refrain from criticism?

Like most episodes of Cold War Civil Rights, the answer permits no simple binary. No one could deny that American racial democracy was undergoing a massive change, and generally for the better, but it’s still difficult to dismiss the congruence between White’s changing views and mounting Cold War imperatives.

Enduring similar fates

Over a decade later, Martin Luther King, Jr endured a similar fate.

Though the post-Civil Rights era celebrates King as a visionary, white and black Americans alike (albeit for different reasons) vilified him for his foreign policy positions and, to a lesser extent, his critique of US consumerism and economic inequality (targets easily branded as “Soviet influenced”).

After a tour of newly independent Ghana in 1957, King visited Nigeria and attributed the squalor there to the exploitative nature of British colonialism. Like White in the previous decade, King called on the US to endorse a world without colonies. King expressed his consternation over the Kennedy administration’s continued diplomatic relationship with apartheid South Africa. His attack on the Vietnam War, though, garnered King the most vituperative reactions.

Likewise, feminist lawyer and black activist Pauli Murray’s autobiography describes her experience applying for a research position on a legal development project in Liberia, an initiative under Truman’s 1949 Point Four program, designed to provide “technical assistance to developing nations”. (Paul Robeson rejected Point Four as double talk, a way to penetrate untapped markets in Africa and Asia.)

Like most Americans involved in public affairs at the time, Murray was subjected to various “loyalty” tests, which were also familiar to many Americans who remembered the internment of Japanese and Japanese Americans in the 1940s. The application was rejected surrounding doubts about Murray’s “past associations”.

Murray was far from a radical, but her tireless activism in the 1930s brought her into the orbit of labour organizers and left wing activists. Though lauding Murray’s character and qualifications, her letters of recommendation – by eminent figures like Eleanor Roosevelt, future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, and anticommunist labour leader A Philip Randolph – “had said very little about my loyalty to the United States” and were deemed insufficiently “conservative” by the selection committee.

“What infuriated me”, she wrote, “was that I was being rejected on the basis of innuendo…’Past associations,’ a catchall term hinting disgrace, raised and left dangling the vital question of my relationship to my country, yet foreclosed any opportunity for me to clear my name”. In a flash of inspiration, Murray realised that her mother’s family comprised “my earliest and most enduring ‘past associations’. They had instilled in me a pride in my American heritage and a rebellion against injustice.”

Present day ‘past associations’

The language of “past associations” should sound familiar in our own time. During his campaign for the presidency, Barack Obama was questioned by many about his own past associates (namely, historian Rashid Khalidi, Reverend Jeremiah Wright, literary critic Edward Said), some of whom opponents branded, unhelpfully, as “radicals” because of their critical statements on foreign policy.

In light of these ideologically inflected incriminations, it is easy to forget what is by now practically a cliché about liberal democracies: Criticism of foreign policy, rather than being inimical to a democratic nation’s interest, is a source of its profoundest strength. As one publisher wrote in the Chicago Defender in 1941, “Opposition [is the] essence of loyalty and devotion to democracy – and a free press.”

Vaughn Rasberry is an assistant professor in Stanford University’s Department of English and Centre for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity.