Open access: Stakes are high at the debates over the future of scholarship

Publishers and academics should look into how to spread the costs and make research outputs more accessible to everybody

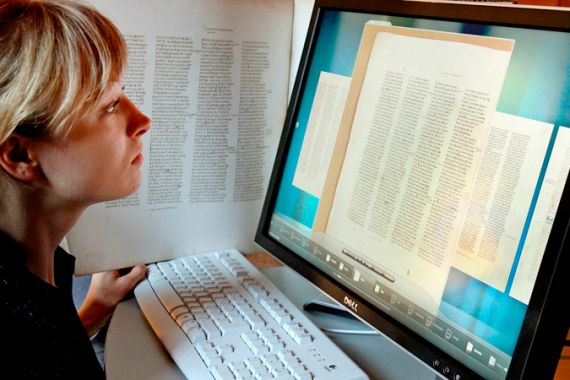

A few years ago, I had a terrific student in my final-year undergraduate module at the University of Leeds. Christie had a real knack for research and was always on top of things.

When the time came for her to write the final essay for my module, she came across a very important article published in a journal our university was not subscribed to. She tried to find a copy everywhere until, frustrated, she spent more than £20 ($32) of her own money to buy an online copy.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThirty years waiting for a house: South Africa’s ‘backyard’ dwellers

Photos: Malnutrition threatens future Afghan generations

From prisoner to president in 20 days, Senegal’s Diomaye Faye takes office

If I recall well, she ended up with a first in my class, so to a certain extent her sacrifice paid off, but the truth is that she should not have been forced to pay for a published piece that was available only to those subscribed.

The case of Christie is representative of a broader problem facing academics and students across continents today. Over the past few months, a heated debate has gathered strength, on both sides of the Atlantic, where European and US scholars, publishers and education authorities are currently scrabbling to find a model that satisfies everybody.

The best-defined positions so far are those of given by the Finch Report in the UK and the American Historical Association in the US. The former argues for full free access to all scholarly research, and for individual scholars and their employing institutions to bear the costs of publication through submission fees.

The latter opposes this model, reasoning that such a move would only replace the unfairness of unequal access with another unfairness, this time relating to the depth of academics’ and universities’ pockets.

Predictably, both approaches have their supporters and detractors. The logic behind the proposals made by the Finch Report is undeniable, especially if we keep in mind that many of these journals are supported with taxpayers’ money, since governments fund much of the research done by universities.

At the moment, many scholars, students such as Christie and members of the general public, cannot read some important pieces of research that have been conducted and published thanks to their contributions to society through taxes and subsidies.

|

|

| Why does US education lag behind? |

Fair as it might seem, however, this approach has a number of inherent problems that were highlighted by the American Historical Association in a statement issued on September 4. This statement raised pertinent questions that should concern not only the academic world, but also the policymakers who legislate on education around the globe.

Free access to academic journals

The competition for resources in these times of crisis is as fierce as anyone can remember. The word “free” in itself nowadays can even carry a revolutionary content. We all know that, for a while now, nothing has been free; as a matter of fact, and in spite of the spread of poverty around the world as a result of the ongoing economic crisis, things keep getting more and more expensive.

For anyone to propose free access to academic journals, you would expect a well-thought rationale to be behind the proposal. To suggest that scholars and students bear the cost of publication through the creation of submission fees is most certainly not the way to solve the problem, as the statement from the American Historical Association has demonstrated with sound arguments.

A world where authors would be forced to pay would create academic environments where scholars and students based at wealthy universities and research centres would always have more opportunities to publish than those who are at the other end of the spectrum, or even those who ply their trade at public institutions – where funds are always limited.

In the UK, such a move could have tragic consequences for many. I have colleagues in some renowned universities who get less than £300 ($480) a year from their employers to carry out research, and thus necessarily need to rely on external funding to cover their research expenses. The scene is no different in the US, as that country is also tightening finances in the education sector.

Is there any reason to expect that the institutions that systematically exploit the labour of this non-tenured academic class would subsidise the costs of their publishing? How can we expect then, that scholars and postgraduate students stomach publication fees, after having done their research – often under the most stressing and financially precarious conditions?

The suggestions made by the Finch Report, as pointed out by the American Historical Association’s statement, would also raise new problems relating to issues such as corruption and quality. A system where authors paid to get published could push journals to publish as much as possible to increase their profits, since their own existence would depend on these payments.

This, in turn, would affect the quality of the pieces published, since publishers would certainly be more likely to prioritise timing and scheduling over the perusal and reviewing of the materials they consider for publication.

Additionally, and relevant as the opinions expressed in the Finch Report and the American Historical Association’s statement may be, they both have omitted a very important issue, that the academic world is not limited to the developed world.

In these documents neither the commission behind the Finch Report nor the American Historical Association satisfactorily address how scholars and postgraduate students in the developing world would deal with any of the proposed changes. It is as if they did not exist and as if the academic journals published in Europe and the US never publish anyone from outside their geographic domains.

Once more, policies that may affect everybody around the world are being discussed and determined by policymakers, publishers and scholars in the developed world – without even consulting their colleagues in developing countries about the consequences that they decisions may have.

|

“Academic knowledge and academic outputs are public goods that we all – scholars, postgraduate students and even undergraduate such as like Christie – should be able to enjoy.” |

Even the comments written by a number of scholars at the bottom of the American Historical Association statement on their webpage have – at least until the moment of writing this piece – all failed to look beyond the impact that these changes are likely to have on their own pockets and careers. Nothing has been said, that I am aware of, until now about how they will affect the rest of the world.

An alternative way?

Perhaps, the first thing that all those involved in this process should do is to look at whether open access will enhance the quality of academic output worldwide, which in my opinion will not be the case. Instead of charging already badly paid scholars and postgraduate students worldwide onerous publication fees, perhaps publishers and academics in general in the developed world should look into how to spread the costs and make research outputs more accessible to everybody.

Perhaps, they could imitate some initiatives already at work that have benefited scores of academics across different parts of the world. One of those initiatives was launched by JSTOR back in 2006, specifically for Africa-based institutions.

According to JSTOR, 750 participants from 43 different countries now take advantage of this scheme and receive partial or full access to hundreds of academic journals free of charge. And JSTOR is not the only case.

The Oxford Journals Developing Countries Offer also allows for free or greater access to all of its journals, while the Gutenberg-E site, sponsored by Columbia University in coordination with the American Historical Association, has put online, free of charge, a wide variety of books that can be accessed anywhere in the world.

Although the Finch Report’s suggestions may at first seem logical and tempting, in reality they may create more problems than they solve. Firstly, they may lead to fewer competitive academic environments where wealth could replace academic rigour as the main drive behind the publication of research.

These proposals also risk making these journals even more elitist and developed world-centred, leaving scholars in Asia, Africa and Latin America – as well as quite a few in Europe and the US – facing a daunting challenge to get their work published.

They also risk alienating a number of scholars who may be forced to circulate their results in other ways, maybe sending working papers via email or publishing them on their own university webpages, limiting the impact of their research.

Ultimately, the various options to offer free access to academic journals must continue to be explored. We cannot just replace one malady with another.

By putting the burden on scholars and postgraduate students through the creation of submission fees, we would be doing a disservice to our pursuit and dissemination of knowledge, and we would almost certainly contribute to widening the gap between scholars and postgraduate students affiliated to rich institutions in wealthy countries, and those who carry out their research work in spite of limited resources and under very difficult conditions in the rest of the world.

After all, academic knowledge and academic outputs are public goods that we all – scholars, postgraduate students and even undergraduate students such as Christie – should be able to enjoy.

Manuel Barcia is Deputy Director at the Institute for Colonial and Postcolonial Studies at the University of Leeds.