Hollywood unveils how the CIA nabbed Geronimo

As a wartime story about a special operation, which killed bin Laden, “Zero Dark Thirty” represents a cultural narrative

The movie, Zero Dark Thirty, about the largest manhunt in the US history will soon be coming to a theatre near you. It is a thrilling docudrama, but told in gripping Hollywood style. Even prior to its official release on December 19, 2012, it garnered several film critic awards.

The hunt for Osama Bin Laden ended in Abbottabad, Pakistan, on May 2, 2011, bringing a painful chapter in history to a close. The mystery of what happened to bin Laden after 9/11 took almost 10 long years to solve, but the movie was completed within approximately a year. It’s released within 18 months from the time of the special operation, codenamed, Geronimo was executed.

Conspiracy theorists abound – many who have been on the bin Laden trail for 10 years – are asking the question “Is this film a piece of art or simply propaganda?” Notwithstanding there are several thoroughly researched books already published on the topic, how is this even possible?

As Walter Benjamin, the literary critic, writing at the time of Nazi Germany, accurately observed, without any ritualistic value, art will be determined by politics. Movies, theatre and drama in the age of mechanical reproduction will inherently be shaped by political culture of the times.

Special access to the ‘vault’

Apparently, the Academy Award winners of Hurt Locker, the duo of Kathryn Bigelow and Mark Boal, were already making a film about Bin Laden’s failed search in Tora Bora in 2001 when the daring mission by Seal Team Six was undertaken in 2011. They ended up re-engineering the entire script.

|

|

| Inside Story – The end of Osama bin Laden |

Yet, the relationship established with the CIA over a long duration was central to getting the story straight, which has been highly controversial. According to several Congressmen, including Peter King of New York, Bigelow received special access to the CIA’s secure “vaults”.

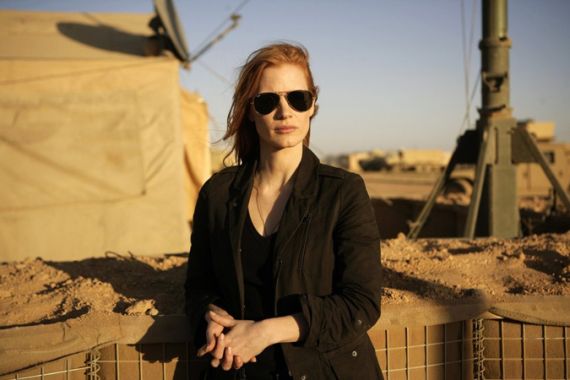

Indeed, the film is all about the inner workings of the agency as the trail for bin Laden blows hot and cold. It would have gone completely dormant if it was not for a singular woman, an undercover agent, named Maya (Jessica Chastain) who stays on the mission, with help from another interrogator named Dan (Jason Clarke).

Maya, the main protagonist in the film, projects onto the screen like a white hot light – beautiful, enchanting, yet ferocious – with fiery red hair. Against the dark, foreboding and swirling backdrop of spy networks and “black sites”, often operating in a parallel universe, Maya’s character carries the narrative forward with her directives and laser beam intuition.

Bigelow strategically places her in the maelstrom of male-dominated networks – interrogators, agents, detectives and diplomats – busy chasing each other’s leads, but failing to nail down the target. Maya is seemingly blocked at every step from going forward due to policy and procedural red tape, but like a good solider she presses ahead.

Female agent versus the veil

Maya represents the epitome of Western womanhood – strong, independent and kick-ass – as a direct counterpoint to the veiled women in the black hijabs and burkas, seen on the streets of Pakistan and Afghanistan, respectively. Women may cheer her on as a liberated individual on either side of the cultural divide, but how the film might be received in the larger Islamic world is an open question.

Her singular mission to get bin Laden will be emblazoned on your brain when you step out of the darkened theatre. In a key scene, she challenges her boss, who is too busy fighting Bush’s “war on terror”, if he does not assign enough resources to follow a cellphone lead which might be crucial to locating bin Laden’s courier, she will demand Congress for a special hearing.

How much of the script is dramatised? How much of it based on what transpired on the ground is not clear. The director and writer claim that it is “based on first-hand accounts of actual events”, a fusing of journalism through film, or what Bigelow calls “an imagistic version of living history”. But how close to reality is the visual journey, as the filmmakers have distilled 10 years of espionage case details into two hours, I asked Seth Jones at RAND Corporation, who advised the filmmakers? He suggested, in the big picture, the film is accurate.

When I interviewed long-time former CIA personnel, he said it is difficult to believe an analyst at GS-13 ranking could have carried out the operation by herself without the full co-operation of her superiors and others on her team. She may have challenged her bosses, fine, but she did get their support. The agency thrives on teamwork, not on Clint Eastwood like “lone wolves”, who buck the system. In the end, the system seems to have worked.

Clearly, the American archetype of a “lone wolf” is projected onto the female agent, as part of “character development”, may be because the filmmaker herself is a woman operating in a male-dominated profession, making two successful wartime films back to back.

In another revealing scene, when Maya interjects in a conversation with the head of the CIA Leon Panetta (James Gandolfini from The Sopranos), she is curtly asked, “Who are you?” “I’m the motherfucker that found that place,” replies Maya. The men all dressed in blue suits, full of testosterone, leave the room speechless. We don’t need a Rorschach test to see the director’s hand in this scene.

Freud taught us all biographies are autobiographical to some degree and storytelling is a subjective art form. Thus, Bigelow’s cinematic vision is shaped by her life-experiences. When it is time to vote on the decision to execute the mission, every stakeholder in the CIA boardroom feels they are roughly 60 percent certain about the presence of bin Laden in the compound in Abbottabad. Maya states categorically she is 100 percent confident that she has found the high value target. After much debate, the mission is carried out and the rest is history.

To torture or not to torture

The opening half-hour consist of long drawn-out sequences of interrogation and torture, including water boarding, which has again raised the ugly debate – “Does torture work to gain real actionable intelligence?” While the experts within the CIA and outside are divided on this issue, the movie gives the distinct interpretive impression that torture did lead to the finding of bin Laden’s hideout.

|

|

| Listening Post – Smoke and mirrors: The bin Laden death story |

The torture scenes are long enough to turn Michel Foucault, the French “anti-Oedipus”, in his grave. He argued that fundamental to all modern societies was the practice of “surveillance” and “control” of every zone of human impulse, action and thought – the nation state thrived on control of the human body down to its very cellular activity – represented by the medieval birth of the prison in the shape of a Panopticon with an “all seeing eye”.

Peter Bergen, the author of Manhunt has said:

“It is a great piece of filmmaking and does a valuable public service by raising difficult questions most Hollywood movies shy away from, but as of this writing, it seems that one of its central themes – that torture was instrumental to tracking down bin Laden – is not supported by the facts.”

Seth Jones, author of Graveyard of Empires, who previewed the film, noted that the within the context of the entire investigation the intelligence gathered from “enhanced interrogation techniques” is a small piece of the entire collection of evidence. Yet, the amount of time spent on enhanced interrogations in the opening of the film might give the impression that it was relatively more important than other critical pieces of evidence.

A report by Boston Globe has pointedly stated:

“The Senate Intelligence Committee, which is finalising its three-year, 6,000-page investigation into alleged torture by government interrogators, has determined that coercive interrogation techniques did not provide the information that led US forces to bin Laden’s hideout.”

Bigelow and Boal are defending their work, claiming the film represents a sampling of the intelligence evidence in an objective manner, but “it is a movie not a documentary”. The viewers can make up their own mind. It is not a partisan narrative, they claim, yet many will find the opening scenes of the film upsetting.

In the Islamic world, certainly, the movie will, at best, receive mixed reviews. When I asked Seth Jones about reactions in the Islamic world, he suggested that certainly the torture and waterboarding scenes might be negatively perceived by people in the Islamic world, including possibly the scenes from the final raid. The film might reinforce the existing anti-American sentiments around the world.

What did Pakistan know?

On the other hand, Zero Dark Thirty does not clarify the role Pakistan, a US ally, may have played in harbouring a high value target for such a long time in a town that is akin to the Pakistan’s West Point. Every serious Pakistani scholar I have interviewed thinks someone in the intelligence community must have known about the compound in Abbottabad. But the movie does not shed any light on this issue.

BBC released a documentary last year claiming:

“Pakistan has been accused of playing a double game, acting as America’s ally in public while secretly training and arming its enemy in Afghanistan according to US intelligence.”

Bruce Riedel, a former CIA officer at Brookings, is on the record in the series claiming, “I told the President Pakistan was double-dealing us and that the Pakistanis had been double-dealing the United States and its allies for years and years….” This is one of the reasons Pakistan may not have been informed about the midnight raid into Abbottabad, at “zero dark thirty” or half past midnight, but the movie leaves these issues simply unexplored.

While a large part of the movie is set in Pakistan, the longtime US ally does not play a significant role in the search or the raid. We witness haunting images of a Pakistani physician, supposedly Dr Shahid Afridi, who manages the vaccination programme and collects data on some of the children in the bin Laden compound, but that programme is abruptly halted. We travel through the bazars of major Pakistani cities, trying to track the cellphone signals from bin Laden’s courier, with informants stationed at every street corner.

With every twist and turn, the audience is led to the final night-time raid which killed bin Laden. “Millions of people around the world will watch the movie and not necessarily read books to understand this complex history,” said Seth Jones.

As a wartime story about a special operation, which officially ended the war with al-Qaeda central, the film represents a cultural narrative – appended as a footnote to the searing memories of 9/11 – that will stay in our public consciousness for the foreseeable future.

Dinesh Sharma is the author of Barack Obama in Hawaii and Indonesia: The Making of a Global President, which was rated as the Top 10 Black history books for 2012. His next book on President Obama, Crossroads of Leadership: Globalization and American Exceptionalism in the Obama Presidency, is due to be published with Routledge Press.