The US presidential debates and comparison shopping

Debates are the only time Americans can evaluate the two candidates side by side; to match them up against each other.

The first point to make about the American presidential debates filling the airwaves over the next several weeks is that they are not really debates. There are few rules, or strict formats and certainly no panel of authorities rendering judgments at the end. They are an exercise in comparison shopping. And herein lies their importance.

The debates are the only time Americans can evaluate the two candidates side by side; to match them up against each other. And making this choice, for most people, just like deciding on who to marry, is not entirely a rational process. Justifications are optional. Concluding “there’s just something about that guy I don’t like” will do.

This gives an advantage to those who are unfamiliar with US politics. Unlike us professional political addicts who listen and analyse every word spoken, you can watch the debates closer to the way most Americans do – Wandering in and out during the 90 minutes, talking with friends and occasionally picking up the non-verbal clues that both candidates may emit. Whose sentences are shorter? Which one seems most relaxed and confident? How about stronger and more decisive? Thoughtful? Who actually seems to be listening?

Candidates in modern American presidential elections have been so programmed by experts – the colours they wear, the gestures they make, the jokes they tell – that the public eagerly looks for any way to get past the facades to figure out what this person actually is about. And so recent debates have turned on seemingly inconsequential acts – George HW Bush looking at his watch as if he had somewhere else to go; Al Gore revealing arrogance by smirking at George W Bush’s assertions; Bill Clinton leaving his lecturn to get closer to the audience member questioning him. All seemed to hint at deeper personality traits. And who can say such clues aren’t more revealing than the candidates’ latest unread policy paper on taxing capital gains.

One example of this comes from the first televised debate in 1960. The event between John F Kennedy and Richard Nixon is often cited as an example of the superficiality of such encounters. Nixon was widely declared the loser, largely because of his gaunt, unshaven appearance, especially when compared to his attractive, articulate rival. Critics pointed out that while people who watched that debate on TV thought Kennedy had won, those who listened on radio gave the advantage to Nixon. The argument was that those who only considered the logic behind the debaters’ statements made a more rational decision than those swayed by appearances.

|

“At the pinnacle of a vast democratic pyramid of government, two men are trying to convince voters that they have what it takes to lead.” |

Perhaps. But those unschooled citizens who decided on the basis of looking at Richard Nixon that they didn’t trust him (the line at the time was “Would you buy a used car from this man?”) have not exactly been undermined by history. After the scandals and lawbreaking and constitutional chaos that accompanied his presidency in the 1970s, intuitively drawing negative conclusions from Richard Nixon’s appearance in 1960 was not a bad judgment to make.

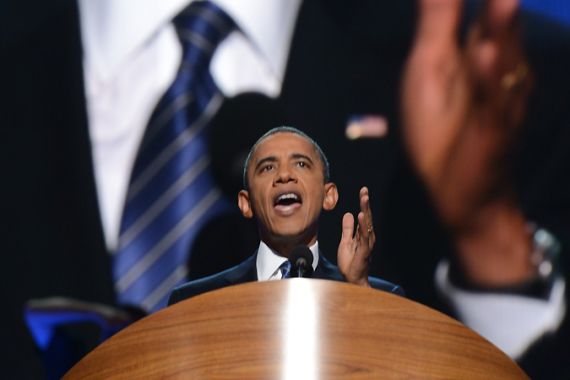

And it will be the moments and sound bites that the press repeats over and over AFTER the Obama-Romney debates that will largely determine the winner. Viewers may want to wait for the press reaction in the days following the debates. For that will be the narrative that largely influences the impact of the encounters. Will Romney reinforce his seeming indifference to the economic fate of average Americans? Or will he appear as the competent manager needed to preserve freedom and prosperity? Will Obama flash an icy reserve toward his opponent and incompetence in rescuing the economy?

Make no mistake about it, the debates may centre on policy differences, on past mistakes and on future strategies but there is only one issue being decided. Who will make the best president? All of these arguments, sound bites and debating gambits are designed to reveal character. At the pinnacle of a vast democratic pyramid of government, two men are trying to convince voters that they have what it takes to lead. And while the press will write their copy, people will draw their own conclusions on a very personal basis – Is he talking down to me? Does he make sense? Does he understand the problems my family faces? Who is this guy and can I trust him?

Through all the campaigns’ obscuring verbiage, the avalanche of money spent on advertising, the endless media spins, the manipulative technologies of targeting, there is something reassuring in seeing two guys on a stage talking to each other. It almost redeems all the B-S.

Gary Wasserman is professor of government at Georgetown School of Foreign Service, Qatar. He received his PhD with Distinction at Columbia University. His thesis, Politics of Decolonization, was published by Cambridge University Press. He has written for The New York Times, Foreign Policy and Political Science Quarterly.