Egypt: The revolution that shame built

Although Bouazizi’s self-immolation mobilised a nation, Egyptians would need to exercise a different tactic for change.

|

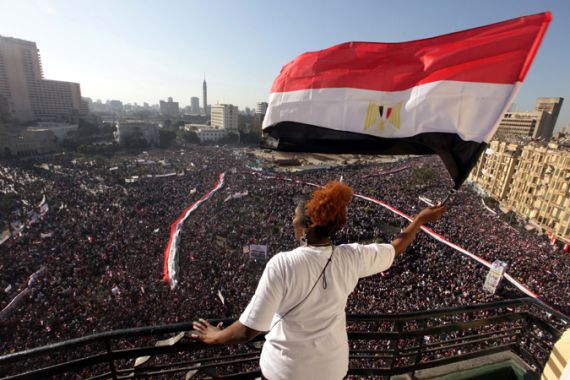

| The call to meet at Tahrir Square on January 25, 2011, was spread by online social media and word-of-mouth [EPA] |

Irvine, CA – They were two “new media” events that changed history, unalterably shifting its course into uncharted waters – not merely in the Arab world, but globally as well. And yet their very impact points to two of the most important weaknesses underlying the past year’s worth of revolutionary protests across the region.

The first, an image shot by a cell phone camera, is heartrending to view, as it shows a young man completely on fire, like a still from some bad horror film. Today the world knows the pain behind the grainy image of 26-year-old fruit seller Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation, which lit the Arab world on fire. A young man, struggling to survive in an economy that had made him and so many young Arabs expendable, suffers one too many indignities, and is driven – or inspired – to stage a death that would give life to the hopes of his generation.

Today, revolutionaries across the Arab world circulate his supposed final words on Facebook: “Maybe by setting myself on fire, life can change”.

Bouazizi’s last Facebook entry was a plea for forgiveness from his mother: “Blame the times and not me.”

“Living in a land of treachery,” he explained, had driven him out of his mind. It was a mental state that was shared by so many of his friends – indeed, for the past decade it has been impossible for me to count how many young Arabs have told me they feel schizophrenic or mentally ill, just from living their daily lives in a system that only crushes them down and offers little hope for the future. And so several young men from Sidi Bouzid told me that, when they heard the news about what he’d done, their first reaction was: “Why wasn’t I brave enough to have been the one to do it?”

A call to action

Across North Africa, in Egypt, pro-democracy activist Asmaa Mahfouz, also 26 years old, watched the unfolding revolution in Tunisia with great anticipation. Bouazizi’s hometown of Sidi Bouzid was a relative backwater, without much of a robust or well-developed public sphere or civil society network to channel his frustrations into more positive action. Mahfouz, however, was a founding member of the April 6 movement, which itself emerged out of the struggle for jobs and dignity by Egyptian workers in the previous half decade.

| Egyptian activists in the information war |

She well understood the despair and the circumstances that drove Bouazizi to take his own life; but, crucially, she also had the training, vision and networks to take the energy unleashed by Bouazizi in Tunisia and attempt to translate it into concrete political action – not merely one time, but multiple times, until her words broke through the wall of fear that had long kept most Egyptians, such as their counterparts in Tunisia, away from political protest. If Bouazizi acted alone and in desperation, her actions were the product of years of preparation, even if the speech on the video was ad-libbed.

And so, if on December 17, 2010, Bouazizi addressed his final Facebook posting only to his mother, almost one month later to the day, on January 18, 2011, Mahfouz put up a video on Facebook addressed to the entire Egyptian nation. “Four Egyptians have set themselves on fire to protest humiliation and hunger and poverty and degradation they had to live with for 30 years,” she declared, setting the context for her call to Tahrir.

“[They were] thinking maybe we can have a revolution like Tunisia, maybe we can have freedom, justice, honour and human dignity. Today, one of these four has died, and I saw people commenting and saying: ‘May God forgive him. He committed a sin and killed himself for nothing.'”

And then she uttered the words that would bring her generation into the streets: “People, have some shame!” (“Ya gama’, haram ‘aleyku!“)

|

“The idea of shame is crucial in the history of the Arab Spring, and not, as the Bush administration’s torture masters would have had us believe, because … Arab men are uniquely preoccupied with shame.” |

The idea of shame is crucial in the history of the Arab Spring, and not, as the Bush administration’s torture masters would have had us believe, because Arab culture and Arab men especially are uniquely preoccupied with shame. Rather, because Mahfouz understood that she had to shame her compatriots out of their passivity in order to awaken a level of political consciousness, and through it agency, necessary to create a powerful, mass-based protest movement against the Mubarak regime.

In simple, yet elegant words, she described how only days before she’d posted another video calling on people to join her in Tahrir, only to wind up joined by “only three guys, and three armoured cars filled with police”, who violently pushed them out of the square, before trying to convince them that those who had set themselves on fire were “psychopaths”. She refused to accept such a characterisation – even though the term evoked precisely the feeling of being “out of one’s mind” that Bouazizi described in his final Facebook posting. But she also understood that while self-martyrdom could launch a revolution in Tunisia, it wouldn’t be enough to do the same in Egypt. Instead, a much more sophisticated discourse and strategy would have to be deployed.

A challenge to a country

Like Bouazizi, she began with the simple declaration that the whole system was “corrupt”. But then she went on to point out the basic flaw in the logic of self-immolation in the Egyptian context:

“These self-immolators were not afraid of death but were afraid of security forces. Can you imagine that? Are you going to kill yourselves, too, or are you completely clueless? I’m going down on January 25th, and from now ’til then I’m going to distribute flyers in the streets. I will not set myself on fire … Instead of setting ourselves on fire, let us do something positive … Sitting at home and just following us on the news or on Facebook leads to our humiliation.”

The time for passivity, for faux-Facebook revolts, was over. Facebook could help spread the word, as her own video would show, but it was no substitute for direct political confrontation in the real world. It was time to take the streets, to take the square. “If the security forces want to set me on fire, let them come and do it,” she added, almost daring the Mubarak government to unleash its fearsome violence against her.

| Revolution through Arab Eyes – Tahrir Diaries |

With this direct challenge to the Mubarak regime and its hated security forces, Asmaa Mahfouz helped to jump-start the process of Egyptians reclaiming their most basic rights – “our fundamental human rights”, as she described it a few sentences later – against a government that for decades ruled at base through the power it displayed to deny those rights to any Egyptian at any time.

At the same time, her challenge wasn’t just to the rulers, it was to the ruled. Setting yourself on fire could be a profoundly political act, but there could, by definition, be no encore. But protesting and demanding one’s rights, by having the courage to die, but the strategic vision to use that courage to challenge the regime over and over again, protesters could move from merely criticising the status quo towards setting an example for a different future and the way to achieve it.

Your rights, my rights, our rights

Most important, Mahfouz understood that shaming her countrymen – and her message, as a young, hijab-wearing woman, was aimed directly, if not exclusively, at Egyptian men – had to be accompanied by a strategy both to convince Egyptians that no-one could any longer escape the violence, while at the same time breaking through the wall of fear that burning oneself to death was a preferable form of protest to risking arrest and torture at the hands of the security services.

“Don’t be afraid of the government. Fear none but God. God says He will not change the condition of a people until they change what is in themselves. Don’t think you can be safe anymore. None of us are. Come down with us and demand your rights, my rights, your family’s rights.”

With these words, Mahfouz was helping to lay the groundwork for Egyptians across the political, economic and generational spectrum to see themselves in the same boat; to bring together yuppies and Ikhwanis, young businessmen (who saw with the brutal torture and death of Khaled Said the reality that they could face a similar fate at any moment). They were joined by ageing leftists, the dirt poor of the Bula’ neighbourhood (near Tahrir) and the comfortably bourgeois of Zamalek, just across the Nile.

“None of us” are safe anymore, because the system has become so corrupt that the old boundaries – which at least created zones of relative safety for those not directly engaged in politics – had disappeared. No more could Egyptians “live like animals”, she declared, when they could have “freedom, justice, honour and human dignity”.

| People & Power – Egypt: Return to Tahrir |

These issues were precisely what the Egyptian workers who inspired the April 6 movement, long the guinea pigs of the process of neoliberalism that also immiserated Mohamed Bouazazi and so many other Tunisians, well understood. And because Mahfouz looked so much like anyone’s daughter, or sister – she could not easily be mistaken either for a Westernised secular activist or a fully veiled Salafi woman, yet could communicate with both ends of the social spectrum – when she talked about “us” and asked viewers to “talk to your neighbours, friends, colleagues and family and tell them to come”, a large share of Egyptian society could feel a connection to her and thus consider heeding her call.

Waiting for Act II

The year since Mohamed Bouazizi’s and Asmaa Mahfouz’s revolutionary outbursts have not gone quite as either of them might have planned. After being hailed as the spark of the revolution, Bouazizi’s family became the source of envy and anger among other poor people in Sidi Bouzid, who resented that his mother accepted a new home in a seaside town and money from Ben Ali. As one friend explained it: “Today hardly anyone talks about Bouazizi anymore.”

But whatever the fate of his memory, the revolution he launched produced the only clear success story of the Arab Spring. For her part, Asmaa Mahfouz and the April 6 movement has struggled to maintain a leading role in a post-Mubarak political landscape that has seen Egypt’s deep state and its well-funded and deeply rooted Islamist movements carve up the emerging political space between them. Mahfouz herself stood up to attempts by SCAF to prosecute her for supposedly inciting violence against the military, but her popularity has been diminished as a result. Her fellow April 6 activists continue to be harassed and charged with such crimes as “attempting to overthrow the regime” and “trying to destabilise the country”.

|

“If the emerging political system begins to look and feel too much like the one so many Egyptians thought they’d helped topple a year ago, the calls to Tahrir will again go out and the ‘couch party’ will again be shamed onto the streets.” |

They will no doubt find themselves between SCAF’s crosshairs again if the “Liars” (Kazeboon) campaign launched against the military begins to show results. At the same time, as most Egyptians have laid aside whatever revolutionary mantle they’d taken up and attempted to normalise their lives, the defenders of Tahrir have increasingly come from the poorest and most marginalised sectors of society – from fanatic football “hooligans” to street kids – who, while representing the majority of Egyptians demographically, are the view in the mirror most Egyptians want to see when confronted by the ongoing violence and repression of the system they’d sought to tear down – beginning a year ago today.

Many commentators have described the ongoing repression and violence deployed by SCAF in the past year as bumbling or incompetent. However, given the extremely weak hand dealt to the military by the revolution, the fact that it has managed to retain a firm grip on power, negotiate an entirely new and seemingly productive relationship with the rising religious political forces, and simultaneously repress the core revolutionary forces – while convincing millions of Egyptians to buy into the new political environment through elections – can only be described as an accomplishment.

But the sparks of inspiration generated by the words, music and images of activists and artists such as Mahfouz, Wael Ghonim or Ramy Essam have yet to go dark. They remain at the heart of the revolutionary impulse that still animates Egyptian politics, whatever the setbacks of the past few months, and no matter who leads parliament when it is seated on January 25.

If the emerging political system begins to look and feel too much like the one so many Egyptians thought they’d helped to topple a year ago, the calls to Tahrir will again go out and the “couch party” – the majority of Egyptians who either sat out the first phase of the revolution or were too quick to leave the square once Mubarak was gone – will again be shamed onto the streets. If not by Asmaa Mahfouz, then by someone who today is as unknown as she was 53 weeks ago. And that is reason enough to celebrate January 25, without reservation and with hope for the future.

Mark LeVine is a professor of history at UC Irvine and Distinguished Visiting professor at the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University in Sweden. His most recent books are Heavy Metal Islam (Random House), Impossible Peace: Israel/Palestine Since 1989 (Zed Books) and the forthcoming The Five Year Old Who Toppled a Pharaoh (University of California Press).

Follow him on Twitter: @culturejamming

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.