Failing to realise the promise of 9/11

After the 9/11 attacks, the US had a golden chance to galvanise the world against terrorism – but it failed to do so.

|

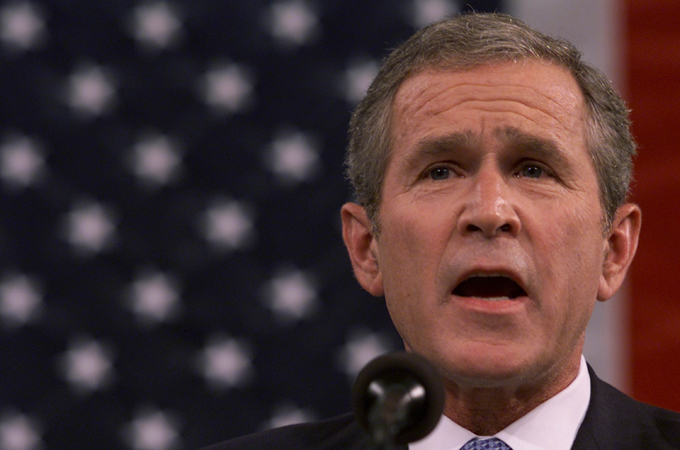

| On September 20, 2001, George W Bush laid out his plans for the ‘War on Terror’ to a joint session of congress [GALLO/GETTY]

|

The 10-year anniversary of 9/11 is a time of retrospectives, both formal and informal. The media, of course, is already rife with them, and there is much more to come.

For many of us as individuals, if we are at all inclined toward introspection, this will be an occasion for reminiscence and stock-taking of a much more personal kind, particularly for those of us who were directly affected by the events of that day, 10 long years ago.

For many and perhaps most of us, recollections of 9/11 are highly coloured by all that has happened since. Indeed, Al Jazeera’s series of anniversary films is entitled “The 9/11 Decade”, a title perhaps fitting for a review of events which, we were told then and many times since, had “changed everything”.

But as someone whose professional career was radically altered by 9/11, I am most drawn to focus on the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks themselves, on a brief period of time before decisions had been made and policies set, before old habits of mind had re-imposed themselves on new facts and new assumptions.

On September 11, 2001, I was the CIA Station Chief in Islamabad, holding the intelligence brief for both Pakistan and Afghanistan. The period from 9/11 to the fall of Kandahar, when al-Qaeda was routed and the Taliban at least temporarily defeated, was a frenetic one, but as I think back over that period, there are two vignettes which I remember particularly vividly, both involving messages to Washington.

The first was written in response to a late night phone call from George Tenet, the CIA Director at the time, who sought guidance and ideas for how we might employ and sequence military actions in pursuit of an essentially political agenda in Afghanistan. Those ideas, transmitted by me in an eight-page cable, were presented to the War Cabinet on Sunday, September 23, and approved by the President the following day. No plan long survives contact with an adversary, but the principles contained in that message were, for the most part, rigorously adhered to throughout the 2001-2002 military campaign. My memory of that message is made all the more indelible by my conviction that our subsequent abandonment of the principles it contained has arguably brought the US and its allies to grief in the mountains and dry plains of Afghanistan. But that is another story.

The second message I most remember, out of the many dozens prepared for high-level recipients in Washington in those days, was one that was, in fact, never sent. It was written in my head, but never committed to dispatches.

The impetus for that message came from what some might think an unlikely source: The speech delivered by President George W Bush on September 20, 2001 to a joint session of congress. In this, his first major post-9/11 address to the nation and the world, the American president laid out his programme for what would subsequently be called the Global War on Terror.

In his speech the President memorably vowed to bring justice to al-Qaeda, and made many demands of the Taliban. But he also went considerably further. Signposts for a much broader agenda were salted throughout his address:

|

“Our war on terror begins with al-Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated … Every nation in every region now has a decision to make: Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists … This is not, however, just America’s fight. And what is at stake is not just America’s freedom. This is the world’s fight. This is civilisation’s fight. This is the fight of all who believe in progress and pluralism, tolerance and freedom. We ask every nation to join us … An attack on one is an attack on all. The civilised world is rallying to America’s side.” |

It is easy in hindsight to see only the belligerence in that State of the Union address. Many of the catchphrases which later came to symbolise the more problematic aspects of the War on Terror are there.But one should also remember the spirit of that moment. It may be hard to imagine now, but there was at that time a great outpouring of sympathy for the United States all around the world, a great sense of international solidarity. It seemed that we were at one of history’s inflection points. Now, I thought, was an opportunity to galvanise the world against the scourge of terrorism, to stand together as a global community to say that wanton violence against civilians, never legitimate, would no longer be tolerated anywhere.

To someone who had spent much of his professional life working against terrorism, this was heady stuff. But as we prepared to invite the Taliban to join the international coalition of civilised nations, and to deal with them if they should refuse, I also knew that the president’s message was badly incomplete.

Winning ‘hearts and minds’

What the president failed to take into account was that with al-Qaeda, the struggle would never be just about terrorists or the willingness of states to confront them. Terrorists cannot long survive in societies which fundamentally reject them. If the US were actually to lead a global movement against terrorism, it would have to find a way to appeal to the many Muslims, including majorities in many countries, who then sympathised with al-Qaeda’s struggle, even as they rejected al-Qaeda’s tactics. It would have to find a way to respond to the young Pakistani Muslims in my own son’s grade school class, many of them from the most privileged families, whose reaction to 9/11 was to say “Now you know how it feels”.

For the world to come together to close the door on terrorism as a political tactic, it would have to open another path to justice for those who felt long deprived of it. And if the US, as the putative leader of the struggle, were to engage on this important front in the war on terror, it would have to commit itself precisely to the quest for justice – whether in Kashmir, in Chechnya, in Xinjiang or, most prominently, in Palestine.

Those were the things I wished to say in that imaginary message to the White House. But prescribing policy is forbidden to intelligence officers, whose role is to inform policy, or to carry it out. And while those rules may have been bent beyond recognition in the case of Afghanistan, where a hitherto obscure field operative was actually asked to recommend policy to the White House, it was hardly an open invitation. As I knew in my heart at the time, the “other half” of the War on Terror was simply not to be.

For the US to assume genuine moral leadership of a War on Terror, it would have had to confront the conundrum at the heart of its policy, to try to reconcile the fact that some of its most prominent “allies” in the struggle against terror were themselves at base the prime instigators of global terrorism. For all that the Bush Administration would speak in later years of a “War of Ideas”, it brought nothing to the fight, other than the self-deluding notion that antipathy towards the US in the Muslim world was based on some colossal misunderstanding.

From a vantage point ten years on, perhaps we can say it didn’t matter in the end. After all, the US could never have simply imposed just solutions for the oppressed on an unwilling world, even if it wanted to. And Muslims themselves have revealed the illusion at the heart of al-Qaeda’s appeal, by mobilising in many parts of the world to seize justice and freedom for themselves, rather than waiting vainly for others to deliver it to them.

The struggle against al-Qaeda may be far from over, but the inevitability of its final defeat is not in doubt. This is true in part because of the devastating tactical losses it has suffered at the hands of the Americans and many others, but more fundamentally, it has been marginalised and rejected by those on whose behalf it has always claimed to act.

Nonetheless, when I look back at that time 10 years ago, it is with the wistfulness reserved for memories of opportunities lost. It may sound jarring to say it, but I will always regret that the country I long served failed then, as it fails now, to seize the promise of 9/11.

Robert Grenier is a retired, 27-year veteran of the CIA’s Clandestine Service. He was Director of the CIA’s Counter-Terrorism Center from 2004 to 2006.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.