Democracies learn from Mubarak’s example

In a worrisome trend, democratic governments have begun to crack down on the freedom of expression on social networks.

|

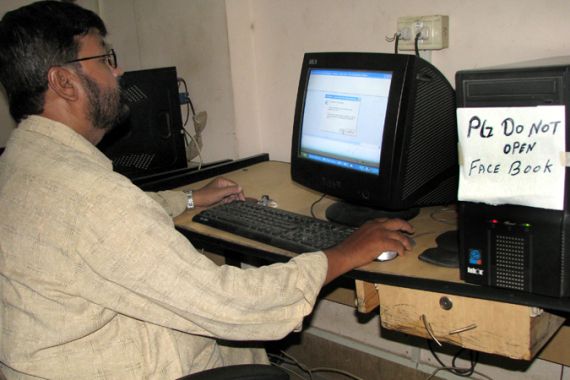

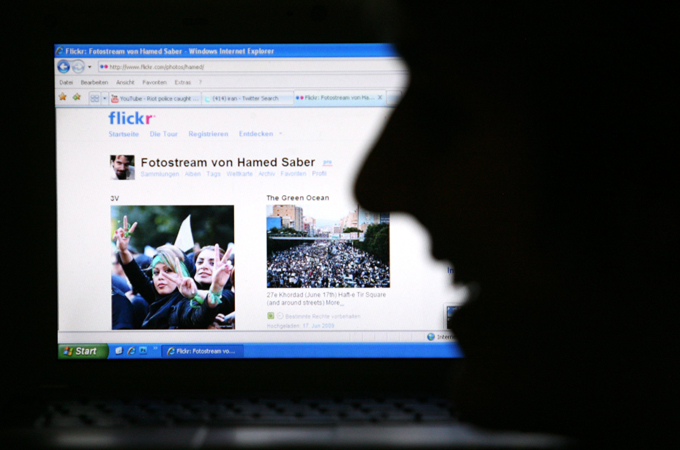

| Governments around the world have begun to feel threatened by social media and online organising [EPA] |

For the past eight months, the world has watched, captivated, as from one country to the next, youth have manipulated the digital tools that have become part and parcel of their everyday lives to serve their activism. The world too has witnessed as, in each country, state actors have made various attempts to quash the use of such tools.

In each case, governments have learned from what came before. While Tunisia’s Ben Ali sought to open up the internet, promising an end to censorship in a speech just one day before fleeing the country, Egypt’s Mubarak took from his failure what not to do, preferring instead to clamp down on social media sites one by one, eventually shutting down the internet entirely. Though Libyan leader Gaddafi followed in Mubarak’s footsteps, finding it easy to shut down dissent among the five per cent of the country’s population that actually has access to the internet, Syria’s Assad took a new approach altogether, opening up access only to then use it against social media users.

But while it comes as no surprise that despots might find new weapons in the digital space, what’s more troubling is the ways in which democratic governments have adapted to the use of digital tools for protest, seemingly taking lessons from their authoritarian counterparts.

Cameron calls for crackdowns

Following days of rioting in London, British Prime Minister David Cameron proposed looking at “whether it would be right to stop people communicating via these websites and services when we know they are plotting violence, disorder and criminality” and noted that he had “asked the police if they need any other new powers”, going on to suggest that Twitter, Facebook, and BlackBerry ought to consider removing messages that might spur further unrest in the country.

Cameron’s calls came just two days after member of Parliament, David Lammy, urged in a tweet for BlackBerry to suspend its encrypted messenger service; BlackBerry responded via Twitter that the company had engaged with authorities to assist in any way possible.

While Twitter took a public stand for its users free expression, and Facebook took measures to remove “any credible threats of violence” from its platform, BlackBerry has remained largely silent, burned, perhaps, by the media frenzy of 2010 that surrounded its negotiations with the Indian and UAE governments. Still, all three companies have plans to meet with UK Home Secretary Theresa May.

Though the UK police no doubt have the right to pursue any individual inciting violence, those powers already exist; tacking on additional measures to censor speech will likely have the opposite effect as intended.

San Francisco transit company ‘pulls a Mubarak’

Amid the news of protests in the UK, a smaller protest was allegedly being planned in the US city of San Francisco. The protest reportedly would have been modelled after a July demonstration during which protesters disrupted Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) services in response to the fatal shooting of passenger Charles Blair Hill, by BART police, on July 3. Though the protest never happened, BART authorities took preemptive steps to quell it nonetheless, shutting down mobile services on several subway platforms in an attempt to block communications.

The move drew ire from civil liberties groups as well as from passengers and the public at large, prompting Anonymous to go after the transit company, taking down one of their sites and publicly displaying user information gleaned by hacking another. On Twitter, the move drew comparisons between the Mubarak government and the BART authorities, inspiring the hashtag “#MuBARTek”.

BART authorities explained the measure by claiming that only certain areas of the subway platforms are available for “expressive” activities, and that paid areas of the platforms are off-limits to expression. And yet, by making available the use of mobile phones in the first place, the action of cutting off access to prevent a potential protest constitutes prior restraint on the right to free expression of all BART customers.

From Tahrir to the States

Both recent incidents indicate an alarming precedent being set. Cameron’s consideration of broad censorship powers echoes similar measures once proposed –and rejected – in Turkey, while the actions of BART authorities have been conducted only by the most extreme of despots.

These are not isolated examples of chilling restrictions on free speech emanating from democracies. In fact, 2011 has been full of prime examples: In July, the Israeli parliament enacted a law banning calls for boycott amidst a growing movement; the law effectively forces self-censorship upon Israeli bloggers, who not only risk penalties for their own writing but also for comments posted to their sites, for which they may be liable.

In India, the world’s largest democracy, a new regulation will soon prohibit intermediaries – that is, any site or content host – from hosting a slew of content, including anything that might be “racially or ethnically objectionable”, or that “harms minors in any way”. The overbroad statute will no doubt scare many intermediaries into submission, resulting in chilling effects on free expression.

And from the UK to South Africa and in numerous nations in between, plans intended to hamper piracy and protect intellectual property continue to put the interests of the entertainment industry before the rights of citizens, instituting in many cases regulations that could block or remove offending sites.

Indeed, it seems that the sentiments expressed by US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton just eight months ago have in many places – including the United States – fallen by the wayside. Rather than moving toward internet freedom, we’re moving toward increased internet censorship everywhere.

.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.