High stakes in Eurasia’s ‘New Great Game’

China and Russia will benefit from US mistakes in Afghanistan, and the operation in Libya, gaining influence and energy.

|

| China is investing on a land-based Central Asian energy strategy – a pipeline-driven New Silk Road from the Caspian Sea to China’s Far West in Xinjiang [GALLO/GETTY] |

Antonio Gramsci once mused that the old order has died but the new one has not yet been born.

While Washington’s geopolitical/energy focus was on Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq and Iran, and to a lesser extent on Central Asia, international politics was already in transition from a unipolar world towards a new, polycentric system.

And then the 2011 Arab Revolt irrupted all across the MENA (Middle East-Northern Africa) chessboard, turning all calculations upside down and reconfiguring the relationship between the US, the main Eurasian nations, and Northern Africa.

Time to recall an ultimate Cold Warrior, Dr Zbigniew Brzezinski, who in 1997, in the article “A Geostrategy for Eurasia”, published by Foreign Affairs, conceptualised that: “Eurasia is the world’s axial supercontinent. A power that dominated Eurasia would exercise decisive influence over two of the world’s three most economically productive regions, Western Europe and East Asia. A glance at the map also suggests that a country dominant in Eurasia would almost automatically control the Middle East and Africa. With Eurasia now serving as the decisive geopolitical chessboard, it no longer suffices to fashion one policy for Europe and another for Asia. What happens with the distribution of power on the Eurasian landmass will be of decisive importance to America’s global primacy and historical legacy.”

US power waning

Fast forward to the first decade of the 2000s. The George W Bush administration devised a strategy for a Great Central Asia according to which the US would roll back Russia’s traditional and China’s growing influence.

Washington would have New Delhi as the partner of choice in Afghanistan and Central Asia – laying the foundations of a new Silk Road.

And Washington would establish itself not far from Xinjiang, in Western China, and close to Russia’s underbelly. Essentially, that’s how the US would win the New Great Game in Eurasia.

This strategy was inbuilt in the Pentagon’s Long War – codename for the Full Spectrum Dominance doctrine – and its far more important, if half-hidden, twin: the global energy war.

In my 2007 book Globalistan, I branded this process as Liquid War; here we would find “liquidity” not only in terms of fast-flowing capital and information shaping liquid modernity (a hat tip to Zygmunt Bauman), but also as in oil/gas pipelines crisscrossing an enormous battlefield, what I have called Pipelineistan.

The problems with the Bush administration strategy may have already started way back in 2003, when Turkey – the bridge par excellence between Central Asia and the Mediterranean – decided not to support the war in Iraq.

Since then, Turkey has gotten closer to Russia and, following Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu’s concept, in fact all its neighbors, especially Iran – performing what could be called an “escape from the US” – and thus denting its role as a NATO base for penetration into Eurasia.

It’s in this context that an Ankara-Tehran-Damascus alliance was solidified (and, incidentally, may now be unraveling). Meanwhile Eurasia as a whole changed at breakneck speed.

Russia was “back” on a continental and also global scale; China and India emerged geo-economically; the US got bogged down in Afghanistan and Iraq. Soon the US was not the “indispensable nation” anymore.

China and Russia

Very few former Soviet states were annexed to the US sphere of influence – as it was expected after 9/11. Moreover, Washington’s dream of a line of control stretching from the Mediterranean all the way towards Central Asia, aimed at cutting in two the Eurasian landmass, did not happen.

China and Russia developed a joint Eurasia policy – organised, among other channels, by the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), the Eurasian Economic Community and now increased military cooperation.

In Pipelineistan terms, China didn’t have to send a single soldier (to Iraq) or get bogged down in an infinite quagmire (in Afghanistan); instead it will get plenty of oil from Iraq and much of the natural gas it needs from Turkmenistan.

China is massively investing in a land-based Central Asian energy strategy – a pipeline-driven New Silk Road from the Caspian Sea to China’s Far West in Xinjiang.

The US’s geopolitical perspective is characteristic of a sea power – framing its relationship with other nations from the position of an “island”; the Mediterranean basin and Central Asia are viewed as placed in a so-called “arc of instability”, as defined by Dr Brzezinski.

Over these past few years, in a constantly evolving context, much more than Great Central Asia, what became paramount for Washington was the geopolitical concept of a Great Middle East – expanding on Brzezinski’s “arc of instability” and running from the Maghreb all the way to Central Asia.

So as much as Brzezinski conceptualised Central Asia as a volatile and unpredictable “Eurasian Balkans”, we had the Bush administration forcefully dreaming of the “birth pangs” of the Great Middle East. The aim was unmistakable; to cause a lot of trouble to the increasing geopolitical union between China and Russia.

Botched operations

In these past few years, up to the – largely botched – Africom/NATO operation in Libya, the US strategy has been aimed at the militarisation of the entire arc between the Mediterranean and Central Asia.

Africom, the US Africa command implemented in 2008 with a headquarters in Stuttgart, Germany, has now engaged in its first African war, in Libya. Africom aims at rapid intervention all across Africa but also has its sights on the “New” Middle East and Central Asia.

So now the US strategy can finally be examined in detail as a militarisation of the Mediterranean-Central Asian arch.

That would assure the US a wedge between Southern Europe and Northern Africa; assure military control over Northern Africa and Southwest Asia, with particular emphasis on Turkey, Syria and Iran; and “cut” Eurasia in two. In sum: divide and rule.

So this geopolitical road map was bound from the start to target Syria (already happening); Iran (a perpetual neo-con dream); and even Erdogan’s Turkey – all useful for a US advance in Eurasia.

Meanwhile Eurasian powers Russia, China and India – all BRICS member countries – not to mention Iran and Turkey themselves, are slowly calibrating their response.

In the midst of this ever-shifting accommodation of tectonic plates, Afghanistan assumes an even more crucial role. It could – and should – recover its status of crossroads/hub bringing Central Asia and South Asia together. Yet that may ultimately happen not under American sponsorship – but under Chinese and Russian partnership.

The Moscow/Beijing counterpunch is to organise the SCO as a rival to NATO in terms of providing security for Central Asia – and for Afghanistan. Wily Hamid Karzai has seen which way the wind is blowing – and he’s all for it.

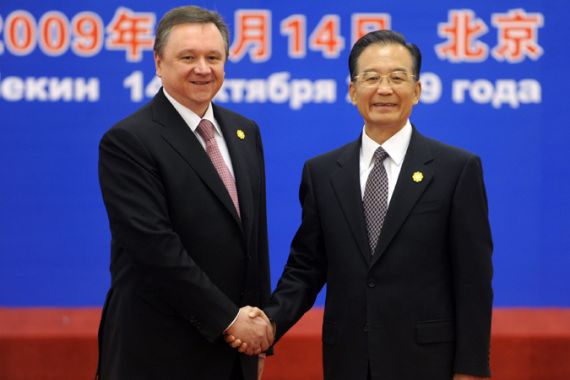

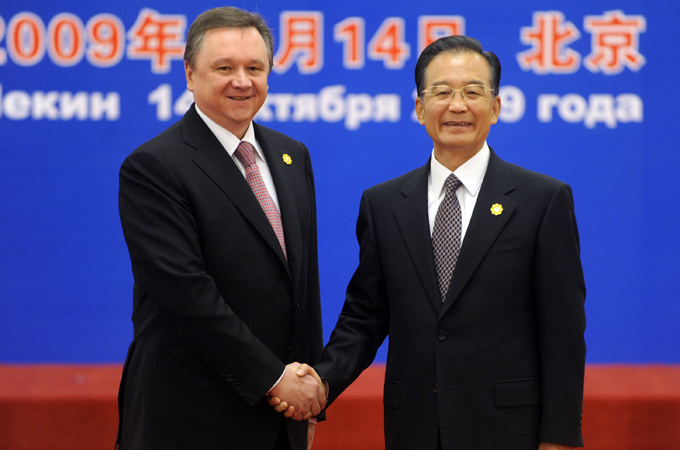

Moscow and Beijing have decided to enter into “tight cooperation” (their terminology) not only in Central Asia but in the Middle East and North Africa as well; Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao admitted as much in a recent op-ed piece for the Financial Times newspaper.

The wake-up call was the Western intervention in Libya. The Chinese economic/political/diplomatic push will be organised under the aegis of the BRICS group of emerging powers (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa).

The complex hidden agendas at play in Syria; the unraveling of the Ankara-Tehran-Damascus alliance; the West’s double standards over Bahrain; Washington’s determination to overstay its military presence in Iraq -these developments are all seen by Moscow and Beijing as part of a strategy to perpetuate Western dominance in the Middle East.

So expect even more feverish moves by the angel of history. Eurasian actors Turkey, Iran, Russia and China will be ever more active in the Mediterranean and Central Asia – the key geostrategic battleground in a 21st century New Great Game that might even be pitting Washington against Eurasia itself.

Pepe Escobar is the roving correspondent for the Asia Times. His latest book is Obama Does Globalistan (Nimble Books, 2009). He may be reached at pepeasia@yahoo.com

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.