Birth certificates and unconscious racism

Institutional racism and racial profiling remain rampant in the US, epitomised by Obama’s birth certificate controversy.

|

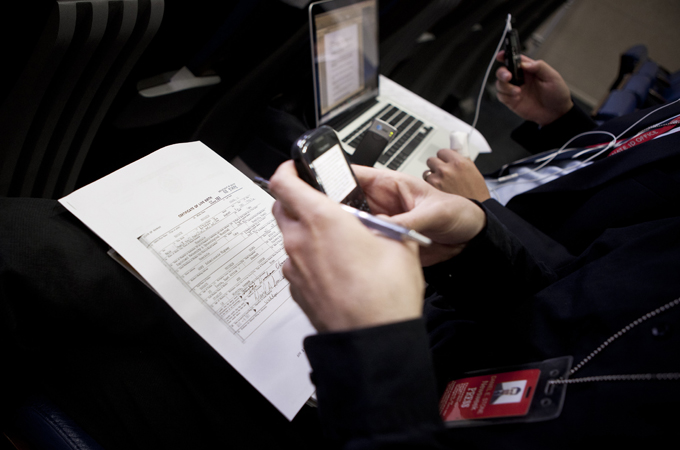

| President Obama has been mired in controversy over publishing his ‘long-form’ birth certificate to prove he is a US citizen – a controversy which many believe is rooted in pure racism [GALLO/GETTY] |

Immediately after president Obama surprised everyone by releasing his long-form birth certificate on April 28, a quickly fielded poll by Survey USA showed that 28 per cent of respondents said they either “still have doubts where the president was born”, or they were “sure the document was forged”.

That was twice the number of those saying that their previous doubts had been put to rest. Results have varied with other polls, but clearly documents alone can’t convince everyone. No doubt, the vast majority of “birthers” would be shocked and offended to be called racists. Donald Trump certainly was.

“I am the least racist person there is,” Trump told Fox & Friends on Monday, May 9. “In fact,” Trump added, “Randal Pinkett [who is black] won on The Apprentice a little while ago, a couple years ago, and Randal’s been outstanding in every way. So I am the least racist person.”

Trump seemed completely unaware that “some of my best friends are black” is a classic tell-tale racist expression, commonly used to preface anti-black remarks.

Similarly, “birthers” seem utterly unaware that in the US, as throughout the post-colonial world, the routine requirement to show papers has a long and painful history as a key element in enforcing the white supremacist order.

So it’s equally unsurprising that many blacks, in particular, would see this clearly as racism. David Cole’s 1999 book No Equal Justice: Race and Class in the American Criminal Justice System provided a detailed examination of how purportedly “equal” treatment produced wildly unequal results at every step of the criminal justice process, beginning with the most basic and most broad – the decision on who to stop for questioning.

In a 2001 New York Times op-ed, “The Fallacy of Racial Profiling” Cole underscored a key finding:

| Police stops yield no significant difference in so-called hit rates – percentages of searches that find evidence of lawbreaking – for minorities and whites. If blacks are carrying drugs more often than whites, police should find drugs on the blacks they stop more often than on the whites they stop. But they don’t. |

They do, however, stop far more innocent blacks than whites in the process. Little wonder that black parents, regardless of class, routinely drill their children in how to act when stopped by the police, something few white parents ever think about.

Racism that transcends wealth and position

We got a high-profile example of this in the summer of 2009, when the eminent Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates – a personal friend of Obama’s – was arrested in his own home, despite having already shown his identification to the arresting officer.

Moreover, Obama himself got into trouble simply for observing, “[T]he Cambridge police acted stupidly in arresting somebody when there was already proof that they were in their own home.”

But proving who you are is just the tip of the iceberg.

Blacks are routinely regarded with suspicion, and treated unfairly as a result – usually without whites even realising it. One study found that whites with a criminal record were more likely to get a job offer than similarly qualified blacks with a clean record – despite all the stories you’ve heard about affirmative action favouring blacks.

No wonder the black unemployment rate is usually twice the white rate, regardless of what that rate might be. Or consider housing. When it came to sub-prime mortgages, both blacks and Hispanics were more likely to be steered into sub-prime loans, even when they qualified for prime-rate loans.

None of this proves conscious racist intent. But that hardly matters to the victims.

Unconscious racism

In a forthcoming Temple Law Review article, “Unconscious Racism”, professor and civil rights attorney David Kairys begins with an example of unconscious racism in a 1960s bail-setting court.

“Two drunk-driving cases about a week apart were identical in all respects except the races of the defendants, but the judge, who was not an overt or self-perceived racist, showed empathy to the white drunk driver while his reaction to the black one was dominated by fear,” Kairys explained, resulting in harsher bail treatment.

As a young attorney, Kairys delicately pointed out the disparity, and the judge graciously corrected himself, reflecting the standard at the time: disparity in treatment was impermissible, regardless of intent. That standard did not last long, however.

In the mid-1970s, a new standard emerged, requiring a showing of conscious racial intent – something often difficult to perceive, much less prove. Then, adding insult to injury, that standard was used to roll back race-conscious efforts to equalise the treatment of blacks.

“Alongside and not unrelated to these legal developments,” Kairys wrote, “non-explicit forms of discrimination against African Americans and other minorities grew in number and significance, and became more easily non-explicit.”

As whites moved increasingly to the suburbs, “whites and minorities were increasingly separated geographically; advantage and disadvantage could be described as a matter of where one lived rather than one’s race.”

White children who grew up benefiting as a result were genuinely innocent of racism on an individual level-and yet their black counterparts who grew up suffering were just as genuinely victims.

Such is the nature of unconscious racism in the US today. It’s easy to ignore if you’re not the victim. Easy to deny it even exists – especially when the president is black.

Until, of course, people start saying he’s not really an American, not really president at all. Then, just maybe, you might start getting the feeling that something’s just not right.

Paul Rosenberg is the Senior Editor of Random Length News, a bi-weekly alternative community newspaper serving the San Pedro Bay area.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.