A tale of two protests

The subdued US reaction to events in Egypt sits in sharp contrast to its previous support for Iranian protesters.

|

| Is the US hearing the Egyptian call for freedom? [GALLO/GETTY] |

Cast your minds back to June 2009 and the aftermath of Iran’s disputed presidential elections. Months of unrest following the re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and severe crackdowns meted out by the state security apparatus captured the airwaves not only in the Middle East but across the globe.

International news organisations devoted considerable time and energy to Iran’s supposed “Green Revolution”. Western governments, already ramping up pressure on the Iranian leadership over the latter’s controversial nuclear programme, piped in with further vitriol against the Islamic Republic, condemning the leadership for its suppression of protesters.

Here is what the US president said back then: “I strongly condemn these unjust actions [by the Iranian state]” against the protesters. The US and the entire world are “appalled and outraged” by Iran’s efforts to crush the opposition. While denying that the US was seeking to interfere in Iran’s domestic affairs, Barack Obama added: “But we must also bear witness to the courage and dignity of the Iranian people, and to a remarkable opening within Iranian society.”

The Iranian authorities responded by attempting to stop those channels of communication that best captured modern protests: Social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter were targeted for closure.

What did the American authorities do in return? They pressed Twitter to continue providing services in Iran by abandoning a scheduled maintenance shutdown in order to aid the demonstrators. According to a state department official at the time: “One of the areas where people are able to get out the word is through Twitter. They [Twitter] announced they were going to shut down their system for maintenance and we asked them not to.” So far so good.

The US government relentlessly pursued the “rights” of Iranians to protest peacefully and without intimidation and continued to castigate the Iranian authorities for the mass round up and ill treatment of demonstrators.

Such was the vehemence with which the US made its feelings known, that the Iranian leadership in turn accused the Americans of instigating the protests in an effort to topple the regime. With over 30 years of bad blood between the two countries, there was little surprise that the instability unleashed in post-election Iran provided a convenient opportunity for the US to unsettle Iran’s rulers.

Selective hearing?

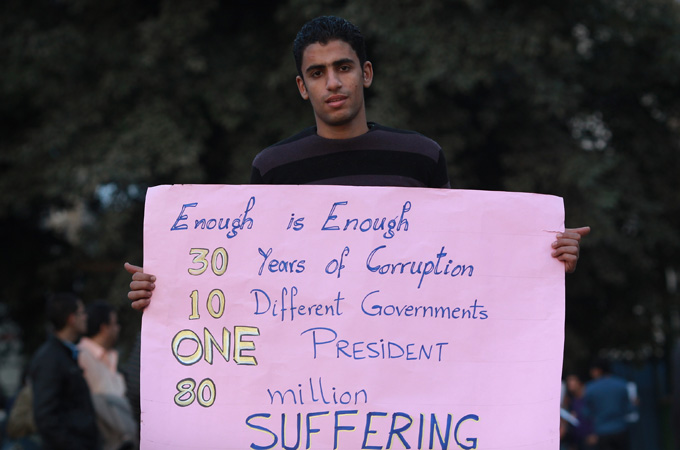

Now fast-forward by less than two years to the present. On January 25, 2011 mass demonstrations broke out in Cairo against a despotic regime which has been politically suffocating a population of some 80 million people for almost 30 years.

Having lived under emergency rule since 1981, the people of Egypt finally rallied for liberty, and in the process braved the worst excesses of a police state. On that day alone, around 860 protestors were hounded by the much-feared secret police, arrested and beaten. Another three were killed. A number of foreign journalists also felt the full force of Egyptian “law”.

The popular revolution train which many “freedom-loving” nations across the world had so keenly anticipated had finally arrived in Egypt. So you would expect the “leader of the free world”, the US, to welcome the cry for freedom in Egypt, right? Well, not quite.

After berating the Iranian government for its heavy-handedness against civilians, senior US officials entered the Egyptian fray with a completely different attitude.

Hillary Clinton, the US secretary of state, offered a particular gem of advice to Egyptians, which inevitably had the effect of rubbing salt in the protesters’ wounds. While urging “all parties” to “exercise restraint” (why the actions of the demonstrators were equated to those of the security forces is anyone’s guess), Clinton added the following caveat: “Our assessment is that the Egyptian government is stable and is looking for ways to respond to the legitimate needs and interests of the Egyptian people.”

Two days later, as the demonstrations showed little sign of ebbing, Clinton’s kid-gloves handling of the Egyptian government similarly showed little signs of wavering. This time, she said, the Egyptian government was facing “an important opportunity to implement political, economic and social reforms that respond to legitimate needs and interests of the Egyptian people”. Many an Arab dictator must similarly be relishing the “important opportunities” ahead to implement change!

As for the need to keep open all communications channels for protesters, reports quickly surfaced that the Egyptian authorities were blocking access to Facebook and Twitter. “We urge the Egyptian authorities not to prevent peaceful protests or block communications including on social media sites,” Clinton retorted. The generous “urge” was unlikely to be heeded.

As the determination of the Egyptian protesters stiffened and the country witnessed an unprecedented bout of “people power” – despite the repression thrust upon them by Mubarak’s ill-disciplined police units – the US found itself increasingly walking a shaky tightrope. With phone conversations between US and Egyptian officials accelerating, Mubarak was now being “urged” to take “concrete steps” for reform.

After five days of unrelenting protests, and sensing that the Egyptian masses were not buying into the US’ expression of concern, American officials finally dropped what to Mubarak would have sounded like a bombshell: “We want to see an orderly transition so that no-one fills a void, that there not be a void, that there be a well thought-out plan that will bring about a democratic participatory government,” Clinton announced.

An “orderly transition” can mean a myriad of things but Clinton was careful to balance her words with a warning against moving to a new government where “oppression” could take root, a not too subtle attempt to taint Egypt’s most popular movement, the Muslim Brotherhood.

Policy by ideology

US policy in the Middle East is naturally driven by ideology and self-interest. It is a policy built on defining allies and foes. Those that have traditionally demonstrated antipathy to US pursuits in the region have been deemed outcasts and vilified whilst those who have acquiesced, to the point of subservience, are flushed with cash and platitudes. The examples of Iran and Egypt are striking in this regard.

Since the Iranian revolution in 1979, relations between the Islamic Republic and the US have been practically non-existent. Given that the revolution itself was fervently anti-American with Iran ridding itself of US influence, the bitterness that ensued is self-evident. Little in the way of compromise has been reached since the early days of the revolution and any rapprochement (however limited) has been met with suspicion and half-heartedness.

That the US blames Iran for a plethora of the Middle East region’s problems and Iran continues to harbour deep distrust of the “Great Satan” is unlikely to change anytime soon. So despite Iran having a political system which arguably allows for real popular representation (the country’s presidency has changed hands six times since 1979, mostly through elections – and no that does not mean that it is liberal democratic) the US is transfixed on finding the smallest fault with Iran and badgering the country into submission.

Some distance west of Iran sits the Arab world’s most populous nation, Egypt. Since the ascension of Hosni Mubarak as president in 1981, the country has been ruled by an iron fist. Not only does Mubarak not tolerate dissent but his regime has imprisoned opponents with such audacity that his antics make Iran look moderate.

Having sat on the presidential throne for almost three decades, Mubarak is showing little inclination to renounce his position or to loosen his grip. Prior to the latest civil unrest, the Mubarak clan was gearing up to the potential elevation of the president’s son, Gamal, as the next ruler.

The severe clampdown on street protesters has brought to the fore the depth of repression which the Mubarak regime has unleashed over many years. Given the disgust with which the president is held in the country, you would think that the global forces of “liberation” would be rallying to the Egyptian people’s cry for help. How wrong, again.

Egypt is the second largest recipient of US military and economic aid (after Israel) in the world, to the tune of some $1.5bn annually. It is the standard-bearer of the “moderate” Middle East camp, as defined by the US. It is only one of two (Jordan being the other) major Arab countries to have signed a peace deal with Israel. It is enforcing the isolation of the Palestinian Hamas movement in the Gaza Strip. It is vehemently opposed to Iran. It does not tolerate Islamic movements and the regime is seen as a bulwark against “Islamism,” notably by suppressing the Muslim Brotherhood. It is a haven for foreign investment and liberal economic policies. All in all, Egypt’s authoritarian leadership is befitting of US policy in the region and therefore Egypt’s interests are the US’ interests.

That the regime can willy-nilly abuse and silence its population is of little concern. Now that the public have spoken, we are told this presents an “important opportunity” for Mubarak to implement reform; reform that has been lacking for decades.

What will happen next in Egypt is uncertain. The street protesters are refusing to be silenced and their brazenness in the face of a well equipped security force is admirable.

The people of Iran will most likely be following events as they unfold in Egypt with keen interest, whether on their satellite receivers or through Facebook and Twitter.

As for the Egyptian people, time will tell whether they will break the shackles of despotism. One thing that is becoming clear to them, however, is this: The US government is proving to be no friend of theirs.

Mohammed Khan is a political analyst based in the UAE.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.