Creative resistance challenges Syria’s regime

Activists online TV programmes, puppet shows and paper newspapers to spread information and mock the elite.

![bashar al-assad puppet [contributed]](/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/20111223124716136734_20.jpeg?resize=570%2C380&quality=80)

|

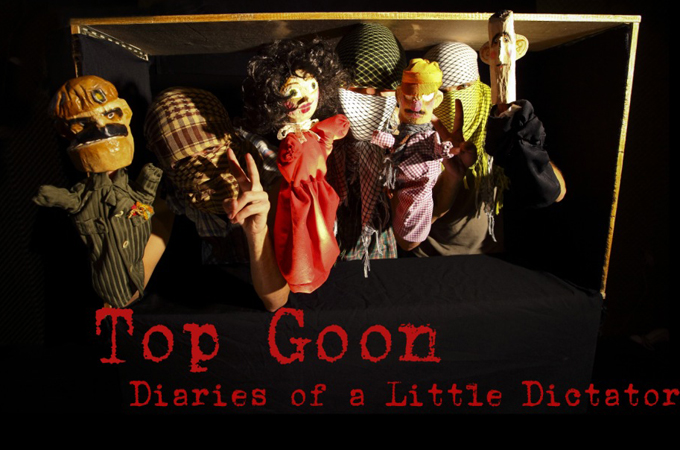

| A satirical puppet show is one of many projects designed to lampoon Syria’s regime [Credit: Top Goon’s Team] |

It may seem like a strange time to talk about music and films in Syria, but artists, armed with a renewed creative mindset, are taking an active role in the struggle against the Syrian regime and the violent crackdown it has launched.

Ana wa bess (Only me) is the latest online release from Abou Naddara, a collective of filmmakers that has been operating from Syria since November 2010.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFire engulfs iconic stock exchange building in Denmark’s Copenhagen

Inside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

‘Accepted in both [worlds]’: Indonesia’s Chinese Muslims prepare for Eid

“We don’t film the revolution, but it’s countershot. This is an artistic decision taken not to put at risk our colleagues who are filming under dangerous conditions. Some of our films even use footage that we shot before the revolution,” says Charif Kiwan, the group’s spokesperson who also distributes the films abroad.

There are no chaotic images in the films and nothing similar to what the public expects or sees on YouTube and other social media. Using evocative images and songs with conflicting titles like The Infiltrators and Corrective Movement that remind of the official regime discourse, Abou Naddara gives shape to films that are sophisticated but never pretentious. A strong supporter of the power of “smaller screens” like computers or mobiles to distribute its work, every Friday the collective releases a new short film on its Vimeo channel, as a tribute and a contribution to the street protests.

Challenging the party line

User-generated creativity has been a distinctive mark of the Syrian revolution. Syrian Artists have dared to challenge the official media discourse with innovative formats that blossomed on the internet, as much as the people have braved the streets despite daily violence.

Top Goon: Diaries of a Little Dictator, a series of 15 episodes which premieres every week on YouTube with English subtitles, combines the Syrians’ inclination to comedy and professional acting with a dark humour that is truly taboo-breaking.

Since its launch, the series has received lavish praise and occasional furious outbursts from audiences who are stunned by its unprecedented lampooning of the president.

The series stars a finger puppet named Beeshou, who clearly resembles President Bashar al-Assad, even in his famous lisp when pronouncing the “s”.

In the first episode, Beeshou is haunted by nightmares, he fears that his people won’t love him anymore, only to be reassured by his aide Shabih (meaning thug) that the majority of the population still love him.

In the another episode, Beeshou is the only contestant in the game show “Who wants to kill a million”, a parody of a famous TV format whose Arabic version is hosted by George Kurdahi, a Lebanese sympathiser of al-Assad’s regime.

It is precisely for its ability to remix real events and characters with parody and dark humour that Top Goon is so provocative and innovative. “Irony will topple the dictator,” says Jamil, a nickname for the director of the online series. “Syrians are stronger than the violence the regime is using against us. As artists, we respond with irony as much as the people in the streets are responding by dancing and chanting, despite the killings”.

“Civil disobedience can be very creative and thus destabilising for authoritative powers”, says a member of NoPhotoZone, a creative collective of artists and activists operating from Syria. The group will soon launch a website and a Facebook page to feature all its activities including human rights documentation, medical and legal assistance, the production of creative videos and songs and paper magazine.

“Paper is as important as the online media, we have to reach out to people who are in the streets and do not have access to the internet,” says a member of the group who`s also finalising an online aggregator for Syrian creative contents.

Art and irony

Traditional forms of art and culture have been revamped, too, by the ongoing creative revolution in Syria. A few years ago, 28-year-old twins and nephews of prominent Syrian filmmaker Mohamed Malas – Ahmad and Mohamed Malas – created the “the theatre in a room” plays.

In Syria you can’t do anything without a wasta (recommendation). We didn’t have access to official theatres, so we decided to make our little room a theatre stage,” said one of the twins. They live in Cairo now, where they moved a few months ago after being arrested in the artists’ demonstration that hit Damascus last July.

“During the revolution we did many shows in Syria. We invited people and staged our plays at home. We even went to Russia and France to stage our play – The Revolution of Today is Postponed Till Tomorrow – until it became too dangerous to work from inside the country.”

“But we are committed – even from abroad – to make our contribution to the struggle for freedom, using the most powerful weapons ever: art, creativity and irony,” the Malas brothers said.

Like the brothers in Cairo other Syrian artists, including Dani Abo Louh and Mohamed Omran in France, have been contributing to the Syrian creative resistance.

“When we saw what was happening in our country, we decided to stage a performance in the centre of Lyon to reach out to the French people,” says Dani, who studied theatre in Moscow.

“That worked out very well, so we thought of making a movie, Conte de Printemps. It took us three months of work, using cheap technologies like Photoshop and Final Cut. We didn’t have funds, but that was the least we could do for our people and their bravery.”

Dani and Mohamed, who are of Christian and Alawi origins – two religious minorities that are believed to be staunch supporters of al-Assad’s regime – are preparing a new film, about torture and political prisoners in Syria.

“We needed freedom to push our creativity out. These new forms of art blossoming out of the revolution are just the beginning. A lot of work is needed, but at least now, minds are free to think about other forms, other messages.”

Donatella Della Ratta is a PhD fellow at University of Copenhagen focusing her research on the Syrian TV industry.

Follow her on Twitter: @donatelladr