Obama’s failed human rights moment

More than 10 years after 9/11, US politicians are expanding the ‘War on Terror’ instead of scaling it back.

|

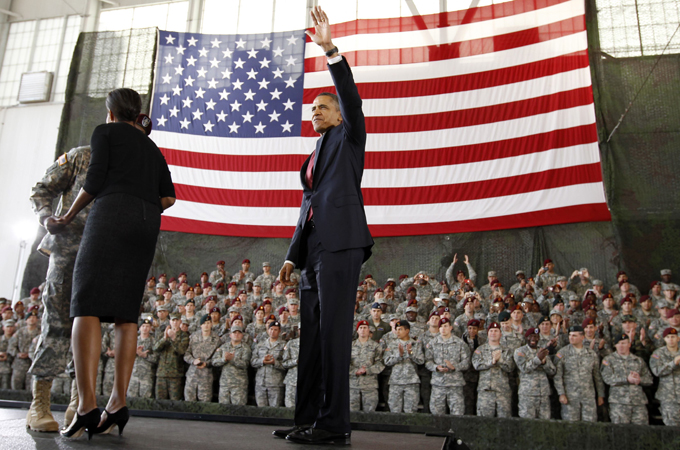

| A bill, which Obama has said he will not veto, would require terror suspects to be tried by military courts [Reuters] |

It is no news that President Obama has been a disappointment to civil liberties advocates (among other segments of the coalition that helped to elect him). But Obama may have hit a new low by retreating from his threat to veto the National Defence Authorisation Act (NDAA), the annual military appropriations bill passed by Congress last week.

The NDAA contains a number of highly problematic detention provisions that undermine the US’ traditions, commitment to human rights and security. Those provisions solidify indefinite detention, militarise US criminal justice and counter-terrorism policy, and entrench Guantanamo, making it more difficult to close the prison. The legislation paradoxically goes much further on these issues than anything Congress did during the Bush administration. More than a decade after 9/11, lawmakers appear intent on institutionalising and expanding the “War on Terror”, rather than scaling it back.

| US Senate passes ‘indefinite detention’ bill |

The NDAA, for the first time, legislates indefinite military detention. Under the bill, any person who is “part of” or who “substantially supports” al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or an “associated” group may be imprisoned without being charged with a crime.

Lower courts, to be sure, have construed an existing statute, the 2001 Authorisation for Use of Military Force (AUMF) to provide a similar detention power. But the NDAA for the first time expressly codifies indefinite detention, making this power more difficult to challenge and more easy to wield aggressively.

Militray detention

The NDAA also for the first time mandates the military detention of covered terrorism suspects, defined broadly to include members of al-Qaeda and associated groups who are planning or who have participated in attacks against the United States. Under the NDAA, the military detention of those covered terrorism suspects is no longer merely an option but a requirement. The NDAA thus creates a new and unprecedented default rule of military detention, usurping the authority traditionally vested in civilian law enforcement. It flouts the principles on which the US was founded: that civilian authority must be supreme over the military, and that even those accused of the most serious crimes are entitled to a trial and the other protections of the Bill of Rights.

Much debate has focused on whether the NDAA applies to individuals arrested in the US, including US citizens. (US citizens are excluded from mandatory detention, but not from the NDAA’s general military detention provisions).

On this point, the NDAA is ambiguous and purports not to alter existing law. The courts, however, have never conclusively determined whether existing law (i.e., the AUMF) allows domestic military detention. The Bush administration used the AUMF to militarily detain only two terrorism suspects who had been arrested in the US – one a US citizen, Jose Padilla; and the other a legal resident alien, Ali al-Marri, whom I represented. Both cases ultimately reached the Supreme Court, but never resulted in a decision because the government transferred the men to civilian custody to avoid a ruling.

The courts will thus again be forced to resolve whether Congress has in fact authorised domestic military detention and, if so, whether it violates the Constitution. The danger, however, is that the NDAA will embolden those who wish to argue that the next terrorism suspected arrested in the US can be locked away in a military jail without charge or trial.

The ramifications of domestic military detention should concern anyone concerned with abuse of government power. Could soldiers seize and imprison a person arrested at his home in say Lincoln, Nebraska, for writing a cheque to a group that supported al-Qaeda? Or a doctor in New York who sent medical supplies to an organisation in Kenya that provided humanitarian aid to a group in that country deemed to be affiliated with al-Qaeda? Rather than making clear that the government does not have this power, the NDAA creates more uncertainty.

Restrictions on president

In addition, the NDAA continues the onerous restrictions that Congress has placed on transferring prisons from Guantanamo. It maintains existing provisions that bar the president from bringing Guantanamo detainees to the US for any purpose, including for continued indefinite detention or criminal prosecution in federal court. It also makes it more difficult for the president to transfer Guantanamo detainees to other countries, even if the administration has concluded after a thorough review that a detainee presents no danger to the US. These transfer restrictions together have rendered the president’s promise to close Guantanamo a dead letter.

The NDAA offered Obama a golden opportunity to reaffirm his commitment to human rights and constitutional values by vetoing legislation that the top military and intelligence officials in his administration opposed as harmful to US counter-terrorism efforts. Instead, Obama withdrew his veto threat after lawmakers made minor tweaks to the bill – for example, by allowing the president (rather than the Secretary of Defence) to waive the mandatory detention requirement and by adding a provision stating that the law would not interfere with law enforcement investigations. (FBI Director Robert Mueller was not persuaded; he maintains that the NDAA will muddle the roles of the FBI and the military notwithstanding Congress’ last-minute revisions).

In explaining the withdrawal of the veto threat, the administration said that the bill no longer “challenge[s] or constrain[s] the President’s ability to collect intelligence, incapacitate dangerous terrorists, and protect the American people”. In other words, what matters is preserving executive power, not protecting individual rights. And while the NDAA still rides roughshod over the Constitution, it apparently now does enough to protect executive prerogatives for the president to sign it into law.

Ironically, last weekend Obama issued a proclamation reiterating the universality of human rights and the US’ solidarity with “all those who reach for the dream of a free, just and equal world”. But, as Obama’s reversal on the NDAA shows, preaching about human rights is one thing. Acting to defend them is another.

Jonathan Hafetz, a professor at Seton Hall Law School, is the author of Habeas Corpus after 9/11: Confronting America’s New Global Detention System.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.