It’s now or never for DR Congo

As Congo prepares for elections, the people must reject corrupt leaders and elect one who shares their aspirations.

|

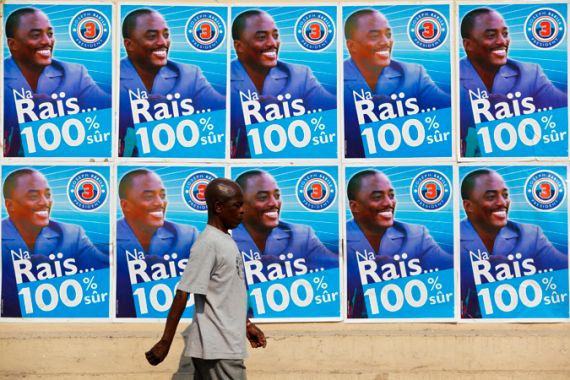

| DR Congo’s current president, Joseph Kabila, has little to show for his nearly 11 years of rule [EPA] |

Contrary to what ill-informed international media keep repeating, the general elections of 2011 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are the third, and not the second, democratic elections held in this country since its independence in 1960.

The first post-independence elections took place in May 1965. They were organised by the Congolese state, and they were free and fair. There was no violence, and the verdict of the ballot box was widely accepted by the electorate and the candidates. Election results were disputed in only five of the 137 parliamentary constituencies.

This historical reference is all the more important today, in light of the democracy deficit of the DRC and most African countries, where the reluctance of incumbents to leave office leads them to resort to intimidation, violence and electoral fraud for purposes of retaining state power. This is what is happening in the DRC today, as the country prepares to vote for the president and members of the national and provincial assemblies on Monday, November 28.

The Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI) has no autonomy, as it works closely with the government of President Joseph Kabila, who is seeking re-election. Pastor Daniel Ngoy Mulunda, the Methodist minister who heads the commission, is a relative of the president and a founding member of the ruling party, the People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD). His performance so far has not shown any signs of impartiality.

The electoral commission has refused to allow for an independent audit of the voters’ roll, which is known to include minors, Rwandan citizens and ghost voters, while real voters have in many instances found their names deleted from it. The commission did belatedly release a map of polling stations, but many of these have been found to be non-existent.

Unfair advantages

In areas favourable to the opposition, polling stations have been reduced in number so as to compel voters to go further away from their homes to a polling place, which is likely to discourage some of them from voting. Laws requiring that managers of state enterprises and other public officials running for the national and provincial assemblies must resign before being recognised as candidates have not been enforced, thus allowing President Kabila’s allies to use state resources for campaign purposes. This is not only illegal, but an unfair advantage for the president’s camp over the opposition.

In this regard, and given the huge crowds that have greeted opposition presidential candidate Etienne Tshisekedi all over the country, there is no doubt that he would win a free, fair, transparent and non-fraudulent election. Of the ten candidates running against Kabila for the presidency, Tshisekedi is the only one capable of beating him decisively, even in a single-round election, because of his standing as the foremost leader of the Congolese democracy movement since 1980.

As the leader of the oldest opposition party in postcolonial DRC, the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS), which was established in 1982, Tshisekedi is popularly referred to as Ya Tshitshi [“Big Brother Tshitshi”] and “the people’s candidate”. He is the one candidate who incarnates the deepest aspirations of the Congolese people for freedom and material prosperity, and epitomises their determination to get rid of the current regime, which has kept the Mobutu legacy of corruption and repression alive.

Since coming to power following his father’s assassination in January 2001, Joseph Kabila has little to show for his nearly 11 years of rule. He won the 2006 election partly on the claim of having ended the Second Congo War, which ravaged much of the eastern part of the country between 1998 and 2003.

However, northeastern Congo remains a zone of turbulence, in which a succession of armies and militia groups, both foreign and national, have plundered the land, subjected women and girls to horrific acts of sexual violence, and used forced and child labour to amass wealth through the illegal exploitation of minerals and other resources. According to reports by the United Nations Group of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of the Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of the DRC, prominent members of President Kabila’s entourage are among the beneficiaries of this plunder.

Plundering Congo

The regime has participated in the plunder either actively, as through mining contracts overwhelmingly favourable to foreign interests, or by acts of omission, for example in doing nothing about the plunder of Congolese resources by Angola, Rwanda and Uganda. Estimates of money lost by the DRC in mineral concessions by self-serving Congolese officials, including the president, are as high as $5.5bn.

In addition to Rwanda and Uganda, which have been plundering the Congo either directly or through proxies since 1996, Angola has occupied land rich in diamonds in the Bandundu province of the DRC and exploits petroleum in Congolese territorial waters. These challenges to national security do not seem to provoke the kind of patriotic response that one would expect from a government whose first priority is to defend the national interest. The president, his cabinet, senior army and police officers as well other high-ranking state officials have done nothing but enrich themselves to the detriment of the mass of the people.

Consequently, the DRC has earned the distinction of being the poorest country on the earth when it is probably the first in terms of its wealth in natural resources. In the 2011 Human Development Report of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the DRC is the last of 187 nations surveyed in terms of its Human Development Index (HDI), a measure of wellbeing based on life expectancy, personal income, health and education. It is therefore beyond comprehension why Joseph Kabila should pretend to be “100 per cent” sure that the Congolese people will give him another five-year term in office.

This is both a manifestation of utter contempt for the electorate and an expression of confidence in the electoral fraud machine being organised and managed by Pastor Ngoy Mulunda. For there is widespread belief among African leaders that it is stupid to lose an election that you organise. Thus, even when so-called independent electoral commissions are established, incumbents will use all the means at their disposal, both legal and illegal, to cling to power.

Now or never

In the DRC, the genuine political opposition and civil society are determined to do all that is necessary to defeat this machine of electoral fraud so that the final results would be consistent with the wishes of the people. This will not be easy, not only for the support that the Kabila regime enjoys from neighboring states such as Angola, Rwanda and Uganda, but also in the face of the hostility of the international community toward the veteran democracy leader Etienne Tshisekedi.

The major powers, in particular, do not like to be faced with a leader like him who enjoys a popular base of support in a strategically important country like the DRC. They prefer leaders with no strong national constituency, who can therefore be counted upon to execute orders from the major world capitals. As ongoing developments in the Arab Spring do clearly show, the Western powers’ supposed support for democracy is a sham, given the hypocrisy and double standards shown in their actions. For if democracy is good for Tunisians, Egyptians and Libyans, it also ought to be good for the peoples of Yemen, Bahrain, Syria and Palestine.

For the Congolese people, this is the third time that our country faces a critical choice concerning its destiny. The first was in 1960, when Patrice Lumumba, the hero of the independence struggle and the first democratically elected prime minister, was wrongfully removed from power and eventually assassinated on orders from the US and Belgian governments. This crime was so profoundly felt by our people that it gave rise to a popular social movement for a “second independence”.

The second time occurred during the African Spring of the early 1990s, as country after country rose up against one-party rule in favour of multiparty democracy. In the DRC, Tshisekedi was democratically elected as prime minister in 1992 by the sovereign national conference with a mandate to bring about radical change in the way in which the country and its resources were managed.

Unfortunately, the international community gave him lukewarm support and did nothing to prevent the restoration of the Mobutu regime after a few months. After losing 20 precious years and after 50 years of seeing their country fall to the bottom because of corrupt leaders, the Congolese people are determined to put in power a person whose vision of the future reflects their own aspirations. For them, it is now or never.

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja is Professor of African Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.