FARC leader dies, civil war continues

Despite concerns FARC will become fractured, the same grievances remain so Colombia’s civil war will continue.

|

| ‘Having lost many leaders before, the FARC is no stranger to restructuring and adapting’ [EPA] |

Colombian soldiers in the war town Cauca region, Southern Colombia, are making the most of the recent death of Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) leader Alfonso Cano, 63. Every day since government forces finally found the guerilla leader, a mere two hours from the city of Cali, they have been using leaflets and other means, to reach out to FARC troops and call for them to demobilise.

“They have just lost their leader, we are sure they will be keen to demobilise, now is a big opportunity for us,” said a local commander.

Despite the commander’s optimism, and a much needed morale boost for the Colombian army, the death of Cano brings the conflict no closer to an end. Having lost many leaders before, the FARC is no stranger to restructuring and adapting. As was seen after the death of FARC leader Mono Jojoy in September 2010, there were no mass desertions, instead, his successor simply took over the position and the FARC’s control of the region continued almost unaffected.

As a whole structure, however, the FARC could be affected. Despite Cano sharing all decisions with a seven-man secretariat, the increasing military pressure could start to severe communications between commanders. While the government may be rejoicing, this is likely to create a more dangerous and violent situation in the country. As FARC commanders become autonomous – and left to their own devices – in order to generate income, they could increasingly work with drug gangs controlling the cocaine trade. Heavily armed, well trained, this could pose an even bigger problem for the state further down the line.

Another problem with breaking down the FARC is, the government will be making it increasingly difficult to negotiate with the guerilla army as a whole. In recent months, it is reported the Cano was trying to gain support among the rebel ranks for renewed peace talks. In a video message a few months ago, he reiterated that he believed a peaceful dialogue was the only way to end the conflict.

It is disputed locally whether the next two candidates will be as open to negotiations as Cano was. Some believe that one of the contenders for the top job, Ivan Marquez, is considered by the government to be the FARC leader who will bring the group to the negotiating table as a result of his involvement in the 2001/2002 peace talks. However, many analysts assert that Marquez and Timochenko are more radical and military minded than Cano.

A lack of ideology and criminal ties

Alfonso Cano – real name Guillermo Leon Saenz – had gone from the bourgeois suburbs of Bogota and the prestigious environs of the National University to the then-Soviet Union and returned to preach his fiery Marxist rhetoric in the jungles of the FARC heartland. He rose quickly among the ranks of the leftist rebels and became leader of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – better known by their Spanish acronym, FARC – in 2008 after the group’s founder, Manuel Marulanda, died of a heart attack.

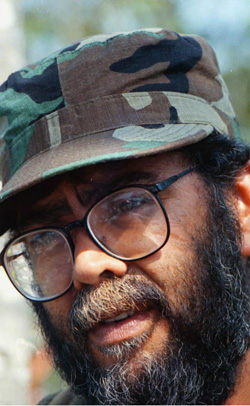

|

| Alfonso Cano had two aims: Guerilla attacks and ideological teaching [EPA] |

Owing to his education and commitment to Communism, before his involvement with the military, Cano was considered one of the last intellectual FARC leaders. Soon after taking over leadership, he began Plan Renacer. One part of this initiative was to increase guerilla tactics, including assassinations, bombings and targeted economic sabotage. Another part was to restart ideological teaching, which the FARC has been criticised for losing over the years. Without such an ideologue as their leader, the dangers of the FARC becoming violent for economic means are greater than ever.

Lacking ideology, and with closer ties to the criminal groups, it is less likely that certain FARC cells will negotiate with the government. Running drug trade routes is huge business, and detached from their leadership, it is unlikely that these groups will give up their riches to languish on demobilisation schemes, which see former FARC members sent to live in poor slums with little support. Instead, these FARC groups will become stronger and more of threat to the state then they were under the leadership of Cano.

Another concern regarding an increase in ties between FARC and criminal groups is, the effects this will have on civilians. The main FARC areas now lie on indigenous land, and relations continue to decline as the indigenous demands for autonomy conflicts with the FARC’s methods for command and control. Lacking in ideology and moral leadership, the suffering of indigenous people can be expected to increase. As the FARC care increasingly about their drug routes, and the indigenous people are seen as an obstacle or risk to their incomes, there will be more displacement and targeted assassinations of indigenous leaders.

A pressing concern for civilians living in and around conflict areas is, the expected retaliatory attacks by the FARC. In the past, when the guerillas have lost strategic land, or a top leader, they have often increased military attacks in order to assert their power. Already, since Cano’s death, several attacks have been launched across the country. Just on Saturday, a bomb was detonated in Toribio close to where he was killed. The mayor, six civilians and three policemen were all injured in the attack. More is expected in the coming weeks.

While the government may have hopes to reach out to the new leadership and eventually put an end to the violence, the conflict is only expected to escalate.

FARC: No end in sight

Following Cano’s death, Colombian President Santos was quick to call on the FARC to demobilise. “I want to send a message to each and every member of this organisation; demobilise. Because if you don’t, you will end up in jail or in a coffin.”

The FARC were even quicker to reject his calls. “This is not the first time that the oppressed and exploited in Colombia are mourning one of its great leaders. Nor the first to replace him with courage and conviction in our fight for victory,” the FARC said in a statement. “Peace in Colombia will not be achieved by guerrilla demobilisation, but by the abolition of the causes that give rise to the uprising. We have a policy laid down and it is to continue.”

Local reports suggest that Santos will announce a plan for renewed dialogue with the FARC before 2013, towards the end of his term. With both sides expecting this, there will be an increase in violence over the coming years as both militaries attempt to gain leverage when it comes around to negotiations.

While some commentaries are heralding Cano’s death as the beginning of the end for the FARC, others believe that his death was a step backward in the struggle to end the conflict. Many, who are also critical of the guerillas for their human rights abuses, indiscriminate killings and forced recruitment of children, say Santos began his position with words of compromise but ended up killing the FARC leader seemingly most willing to enter into peace negotiations.

Having come under fire recently for allowing a significant rise in FARC attacks and insecurity across the county, Cano’s death could be more of media victory as opposed to military. Having been on the run since 2008, the FARC was expecting Cano’s death and more than likely had a plan to quickly shift leadership. While the death will undoubtedly have some damaging effects, the FARC are more likely to just carry on as they were before.

In their eyes, the same oppression, exploitation and poverty remains in Colombia, and they have no reason to demobilise or give up their fight. Ariel Avila, from local think-thank Nuevo Arco Iris says, “You can’t destroy a five-decade peasant revolution by killing one leader; they are not just going to surrender in return for nothing.”

William Lloyd George is a freelance correspondent reporting on under reported stories around the globe. Follow him on Twitter.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.