Tea Partiers: The self-hating 99 per cent

Although the Tea Party and Occupy movement share surface similarities, they represent opposite world views.

|

|

The Tea Party and ‘Occupy’ movements are both angry, but for very different reasons [GALLO/GETTY] |

I suppose it was inevitable that the burgeoning Occupy Wall Street movement would be compared with the Tea Party, but the level of misunderstanding and myth surrounding the latter’s “populist” bona fides is surprising to even the most cynical observer.

There may be surface similarities between the two uprisings, but they actually represent two opposing populist worldviews, whose only philosophical resemblance to one another is their belief that they speak for “the people” against the elites. While both movements are mainly concerned with economic issues, their beliefs about the causes and solutions they propose couldn’t be more different.

One of the central myths about the Tea Party is that it came about as a reaction against the Wall Street bailouts. It’s true that there were some scattered “Tea Parties” around the Ron Paul campaign in 2008, but virtually everyone agrees that the movement was really galvanised by a famous rant from CNBC anchor Rick Santelli from the trading floor of the Chicago commodities exchange.

Only one month into the Obama administration, Santelli called for a “new Tea Party” to be held on tax day, April 15, and it became an instant YouTube sensation and rallying cry for the right wing.

He was mad about bailouts alright, but not the Wall Street bailouts. What sparked his fury was the proposed plan to help average homeowners in trouble with their mortgages. Santelli raved: “Do we really want to subsidise the losers’ mortgages? This is America! How many of you people want to pay for your neighbour’s mortgage? President Obama, are you listening? How about we all stop paying our mortgages! It’s a moral hazard.”

|

“Do we really want to subsidise the losers?“ – Rick Santelli, CNBC anchor |

Here’s how his colleague Lawrence Kudlow characterised the outburst: “Santelli called for a new Tea Party in support of capitalism. He’s right.”

Support for capitalism – and antipathy toward government interference in it – is the very essence of Tea Party populism. There wasn’t much talk about the moral hazard of a “too big to fail” banking system but there was plenty of fulminating about government interference in “the market” and righteous anger about the stimulus plan and what they characterised as the “government takeover” of the healthcare system.

It was never about corporate greed, but was about the usual right wing resentment at the government spending their tax money on people they don’t think have earned it. These are not billionaire bankers – they are the people on the lower rungs of the ladder. Unsurprisingly, this attitude turned out to be useful to corporate interests looking to allay any real populist impulses among the citizenry, and they soon moved in through various means to help the “movement” organise itself.

Contrary to various accounts surfacing lately ostensibly to warn the Occupy Wall Street supporters of the dangers of being similarly “co-opted” it was a very happy love match, not a marriage of convenience.

Occupy Wall Street, on the other hand, while being endlessly harrangued by wags and pundits about its alleged lack of goals and lists of grievances, is actually focused pretty clearly on the same thing as the populists of the Gilded Age – those whom Teddy Roosevelt called the “malefactors of great wealth”.

Their rallying cry is “we are the 99 per cent” which represents the huge number of those of us who have been treading water or losing ground over the past 30 years, while and the upper one per cent of the population swallows up more and more of the nation’s wealth. This shocking income inequality is finally reaching a critical mass that is animating the OWS movement.

Indifference of the rich

This movement wasn’t catalysed by a wealthy commentator issuing a cri de guerre on a stock market show on TV. There has been a growing anti-corporate populist critique on the left for nearly 20 years, first in the form of the anti-globalisation movement and more recently in the more mainstream response to a series of assaults on workers’ rights, notably in Wisconsin and Ohio.

The arrogant indifference of the very rich to the carnage they left behind in the wake of their spectacular meltdown in 2008, and the apparent impotence of democratic institutions to hold them to account, has finally mobilised the masses.

|

‘Occupy’ protests go global |

There is a sub-text that ties plutocratic venality and greed to the political process, but the latter is as much a symptom as a cause. Money has always been influential in politics (and probably always will be), but the corporate takeover of US politics that culminated in the Citizens United decision created a money race that may have led to mutually assured destruction of both parties. All that money bought an economic downturn that continues to plague the lives of average Americans, and Occupy Wall Street is pointing a finger right at the source of the problem. It’s right there in the name.

Historian Michael Kazin, author of The Populist Persuasion: An American History, says: “Right-wing populists typically drum up resentment based on differences of religion and cultural style. Their progressive counterparts focus on economic grievances. But the common language is promiscuous – useful to anyone who asserts that virtue resides in ordinary people and has the skills and platform to bring their would-be superiors down to earth.”

There was a time when left populism was powerful and vibrant, driven by a workplace-centered labour movement that appealed across many of the usual political fault lines and resulted in the enactment of the New Deal, out of the ashes of the Great Depression.

The egalitarian ideas that underpinned that great achievement stood for many decades as the middle class, buoyed by its success, grew to be broad and deep. And that, perversely, led to the opening for the cultural and racial resentment that characterises right wing populism.

Once the left moved to broaden its economic gains to include traditionally marginalised members of society, the right reacted. Strongly. It not only blamed those minorities, but held “pointy-headed liberals” who championed their cause in deep disregard.

After the cultural revolution of the 1960s, this disregard morphed into outright contempt. And that right wing cultural populism has been dominant in the US for the past 40 years, providing cover for the rise of corporatism and the income inequality it buys for the wealthy.

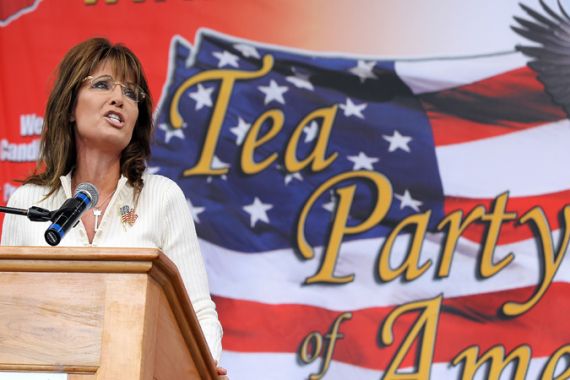

It might be best represented in the person of ex-Governor of Alaska, Sarah Palin, who responded to the question of whether she was smart enough to be president by saying: “I believe that I am because I have common sense, and I have, I believe, the values that are reflective of so many other American values. And I believe that what Americans are seeking is not the elitism, the kind of spinelessness, that perhaps is made up for with some kind of elite Ivy League education …”

A clueless revolt?

One would think that the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street could at least find common ground in their mutual indictment of the political process, however differently they see the cause. But so far, the Tea Party groups are having none of it. The cultural trip wires that have animated rightwing cultural resentment for at least the past 40 years are still powerful motivators – after all, the Rick Santelli rant was based upon resentment of “losers” who needed help with their mortgages.

In recent days, many of them have issued statements denying any similarities with the Occupy Wall Street. Judson Phillips, spokesman for the Tea Party Nation, responded to the claim with this: “The clueless revolt continues and it is painfully obvious those who are showing up to ‘protest’ do not have a job. In most cases, it is painfully obvious why they don’t have a job. To paraphrase the Jimmy Buffett song Margaretville: ‘It’s your own damn fault’.”

Independence Tea Party President Teri Adams was somewhat less flippant but equally unequivocal in her rejection of Occupy Wall Street: “The idea that Wall Street is the root of all evil is an anathema to us.”

| More from Heather Digby Parton: |

|

|

I’m not sure that the Occupy movement’s populism sees Wall Street as the root of all evil, but it does see its reckless destructiveness and craven hoarding of the nation’s wealth as the root of our current national distress. Tea party populism, on the other hand, sees an active government that seeks to redistribute some of Wall Street’s wealth (to the wrong people) as the problem.

It is very hard to imagine that these movements will find common cause. They may both believe that “virtue resides in ordinary people” and that they have the skills and platform to “bring their would-be superiors down to earth” but their definition of who is ordinary and who is superior is radically different.

The United States has always featured these two different sides of the populism coin and it’s tempting to see the two movements arising in virtually the same political moment as representative of a vast uprising of common people in common purpose.

But while it is vast, and masses of common people are rising up, they are two separate movements with very different worldviews.

If one is to take Tea Partiers at their word, they have thrown in with Wall Street and the Occupiers are their enemy. They are already organised around opposing them. The Occupy Wall Street movement does not see the world in such terms. If they are lucky, some of the formerly hostile salt-of-the-earth working folk who might have opposed them on cultural grounds in the past have been radicalised by Wall Street’s greed and will join the occupation.

But I wouldn’t count on too many of them. This is a political and cultural fault line that runs deep. But then again, in this polarised country, all it takes is a few to cross over and make a majority.

Heather Digby Parton writes the liberal political blog Hullabaloo. You can read her blog here.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.

A voice of reason amid the madness

A voice of reason amid the madness