Steve Jobs’ counter-cultural ties

The sense of community Apple helped foster in places like Cairo and Tunis are a part of Jobs’ legacy.

|

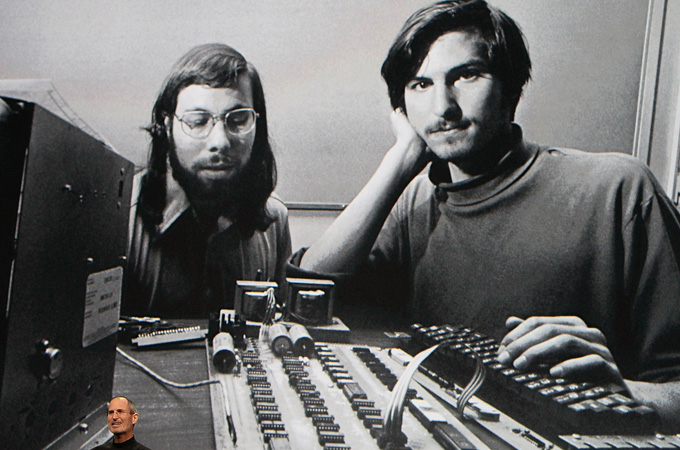

| Steve Jobs and his company projected an image that epitomised modernist consumer style [GALLO/GETTY] |

If you work in the arts it is hard not to be hyperbolic about the death of Steve Jobs. For a large share of the artists, musicians, designers and other arts professionals I’ve met in the last twenty years, owning an Apple was a necessary if not sufficient component of becoming a real artist. Apple has literally become part of our identity.

A Mac seemed to add an extra dose of creativity to whatever you were working on, be it a song, a movie, a website or a novel. It was like performance enhancing drugs for artists and writers.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsHong Kong’s first monkey virus case – what do we know about the B virus?

Why will low birthrate in Europe trigger ‘Staggering social change’?

The Max Planck Society must end its unconditional support for Israel

Of course, such feelings had little basis in fact. Whether you produced a document, design or piece of music on a Mac or did it on a (usually much cheaper) PC shouldn’t have affected its quality or originality. Especially when you could use the same programmes on Windows and Apple operating systems.

Yet there was something about working on a Mac that made you feel like you were better, smarter and more talented. It was like the quality of your creation increased merely by flowing through one of Jobs’ machines. Writing, designing or recording on a Mac was like playing guitar on a Gibson Les Paul or Fender Stratocaster. Yes, other guitars could do the same thing, except that somehow they didn’t. Indeed, their limitations usually became apparent at precisely the moment you needed them to carry your talent to the next level.

Creative DNA

An Apple is like an Ikea desk or bookcase. In fact, Ikea opened its first US store a year after the Macintosh debuted, but with better quality and higher end design.

But unlike Ikea you never felt like an Apple was a mass-produced product. Using it was a personal experience, precisely because it reflected the core elements of modernist design: simplicity, beauty and functionality all interconnected and reinforced each other. Jobs’ aesthetic genius was somehow so embedded into the DNA of his computers and devices that they augmented your own creative DNA.

Or so we’d all like to think.

If anyone should have been favourite target of hackers and virus programmers, it was Steve Jobs and Apple. Yet somehow, despite their incredible success, Jobs and his company managed to project an image that at once epitomised the height of modernist consumer style-Bauhaus for the computer age, and the ethos of the counterculture and the Hacker’s Manifesto. Using an Apple computer, iPod, iPhone and now iPad, opened the door “to a world… rushing through the phone line like heroin through an addicts veins”. You could almost here the computer telling you: “This is it… this is where I belong.”

Of course, true computer geeks didn’t need a Mac to feel this; they had Linux and could interface with their computer at a much deeper level than most artists. They were the guys, like Eddie Van Halen or Jack White, who just built their own guitars. But for the rest of us, switching to Apple meant leaving a “pre-chewed and tasteless” world dominated by “sadists” who wanted to oppress you and the “apathetic” who merely ignored you.

Culture jamming

Indeed, introducing the Macintosh computer with the famous “1984” advertisement during the most commercialised and corporatised moment in American culture, the Super Bowl, seemed, at first glance, like a monumental act of hacking, or at least culture jamming. Jobs was using the Super Bowl to sell a product that, according to the advertisement, challenged everything corporate capitalism represented.

| In deth | ||

|

The advertisement even based itself directly on George Orwell’s book 1984 without securing a license to do so. An act of piracy that ostensibly followed in the hacker tradition. Of course, any similar attempt to utilise Apple’s intellectual property without permission would be met with ruthless retaliation over the years.

Almost a generation later, Apple has become the world’s most valuable corporation. But even when it was the underdog against IBM and Microsoft, the imagination of Apple as somehow counter-cultural was, in retrospect, one of the greatest myth spun by Jobs. Apple was never anything but a corporation intent on maximising profits. Its just that Jobs learned from mentors like Sony chairman Akio Morita that you could charge a premium for better design, functionality, and quality, and still mass produce your products at a profit – the holy grail of consumer capitalism.

Apple workers haven’t fared as well as consumers, however. The super-exploited labourers at the factories producing Apple products, some of whom have killed themselves out of the desperation caused by low wages, impossible production targets, and dismal working conditions – can attest to that sad reality.

Apple’s aura

Perhaps the biggest key to Apple’s success has been its ability to transcend a paradox of modern cultural production first noticed by the great critical theorists of the Frankfurt School in the wake of World War I. They were among the first to demonstrate how mass-produced, commodified culture was becoming not merely a key component of twentieth century industrial capitalism, but a crucial tool for ensuring that the masses accepted rather than challenged the ruling system.

But the power of commodified culture was always a double edged sword. Cultural production had to be meticulously controlled lest it escape and be used to attack rather than prop up the system – thus the symbolism of Apple’s “1984” commercial.

For the seminal inter-war philosopher Walter Benjamin, the mechanical reproduction of works of art and their mass circulation “stripped away the aura” of the work. The almost magical power that allowed a work of art to be experienced should be unique and intrinsically valuable.

Benjamin thought the stripping of the aura from art through its mass production and circulation was a good thing because it allowed for the production of art that no longer served existing power structures. Art liberated from its aura would enable new and even revolutionary visions of the future to be put forth, which held the possibility of liberating the masses from totalising ideologies like fascism or capitalism.

Benjamin’s good friend Theodor Adorno, perhaps the greatest critical theorist of the 20th century, similarly recognised the power of mass produced, commodified cultural production. But he saw the process far more negatively than Benjamin did. Art and cultural production could perhaps be stripped of their natural aura, but that aura would be replaced by the aura of style, the “stereotyped appropriation of everything for the purpose of mechanical reproduction that eliminated every unprepared and unresolved discord.”

| IN depth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In other words, mass produced cultural products and the “culture industry” that fabricated them had little power to expose the contradictions within society that should be the defining function of true art in the modern age. As opposed to Benjamin, Adorno argued that style “represents a promise in every work of art” that can never be kept.

I have no idea if Steve Jobs read Adorno and Benjamin, but Apple achieved its phenomenal success precisely because the aesthetic quality of Apple products seemed to return the aura to the art (or literature, or music or film) produced or listened to on them. Rather than reinforcing “obedience to the social hierarchy,” as Adorno witheringly described the culture industry, Apple actually seemed to deliver on its promise to help us “think different” – the first step on the road to the broader liberation of society.

In retrospect, what Jobs’ designs enabled was an unprecedented “fetishisation” of the commodities he produced. The aesthetic power of the products completely obscure the increasingly exploited labour that went into making them. The myth of Apple as counterculture convinced people they were taking on the system when in fact they were reinforcing it, even as the unique aesthetic properties of Apple products encouraged or enabled greater personal or professional “liberation” for many users.

Planting Seeds in the Middle East

It used to be pretty hard to find Apple computers in the Arab world. Given the high tariffs on imported electronics, the already expensive computers remained out of reach for most computer users in the region, at least until recently. I first noticed people using Apple laptops in the region in the mid-2000s, when following the original rise of Apple Computers in the United States, people in the arts, and especially in design, film and music, began to use them. It is worth noting, that this period was, precisely the time when the “facebook” generation began to come of age and question the quiescence and obeisance of their elders towards the sclerotic regimes that ruled over them.

If Macs gave the illusion of making a difference in New York or Los Angeles, my own experience of them in the Middle East hewed more authentically to the narrative Jobs scripted. I can remember the first time I really noticed an Apple computer in the studio of the Lebanese rock band the Kordz in Beirut. It was a brand new dual core desktop, its silvery aluminium skin projecting power and speed that far exceeded that of my own old G4. We were just beginning to record a song together and the band’s lead singer, Moe Hamzeh, was running recording software on it that I hadn’t seen and creating sounds I hadn’t yet heard.

This was the first time I felt like the region, or at least my musical comrades, had levelled the playing field with their counterparts in the US. But when I heard what Moe could create on it, it was clear that they had jumped ahead, that the “students” were now able to teach their teachers. For me, that computer, it was a thing of beauty, like all Macs, that was direct evidence of the rise of a new generation in the region who would surely do great things one day soon, as I argued in my book, Heavy Metal Islam.

I remember being surprised at the presence of the Mac in the studio but Hamzeh explained that it was the most powerful and fastest computer he could buy, which was precisely what he needed to turn his complex musical visions into reality.

|

“I doubt even Steve Jobs envisioned that scene when he released the first Apple over three decades ago. “ – Mark LeVine |

Half a decade later, in an activist safe house nine floors above Tahrir Square in the midst of the protests that toppled Mubarak, Apple computers once again proved their worth. Upwards of a dozen Macs, including my own, circulated among the scores of activists who passed through the safe house almost every day. We wrote articles, uploaded videos, edited movies, shared files, updated facebook pages, skyped with family and journalists across the world. There was an incredible amount of creativity and energy in the apartment, a degree of shared purpose and mission that has been tragically tarnished, if not lost permanently, with the violence of the last week.

But in those incredible late January and early February days, the young activists had managed to create a sense of community, a counterculture in which, with the help of their Macs, they were “thinking different”.

It’s hard to imagine it all having worked so smoothly if the revolution made largely on Windows. One thing was for sure, the thugs at the Interior Ministry weren’t working on Macs.

Of course, the brand of computers favoured by activists had no practical impact on the successful overthrow of Mubarak, or Ben Ali before him. But working late into the night as violence and uncertainty flared in Tahrir and the surrounding streets below, there was something comforting about the glowd, or better aura, of so many apples in that darkened apartment, linking everyone together just a bit more tightly than they otherwise would have been.

I doubt even Steve Jobs envisioned that scene when he released the first Apple over three decades ago. But the sense of community Apple helped foster in places like Cairo and Tunis earlier this year are as much a part of his legacy as the iPad or iPhone. The cultures they helped create have now spread back to the US where, as I write these lines, iPads, iPods, iPhones and Macbook Airs are no doubt helping to inspire a large share of the Occupy Wall Street protesters as they sit late into the night, planning yet another, still nascent revolution.

Let’s hope that soon Apple products can also help liberate the underpaid and highly exploited workers who make them.

Mark LeVine is a professor of history at UC Irvine and senior visiting researcher at the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University in Sweden. His most recent books are Heavy Metal Islam (Random House) and Impossible Peace: Israel/Palestine Since 1989 (Zed Books).

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.