Tunisia: trouble in paradise

The protests in Tunisia reflect an underlying dissatisfaction with the government that stretches years back.

|

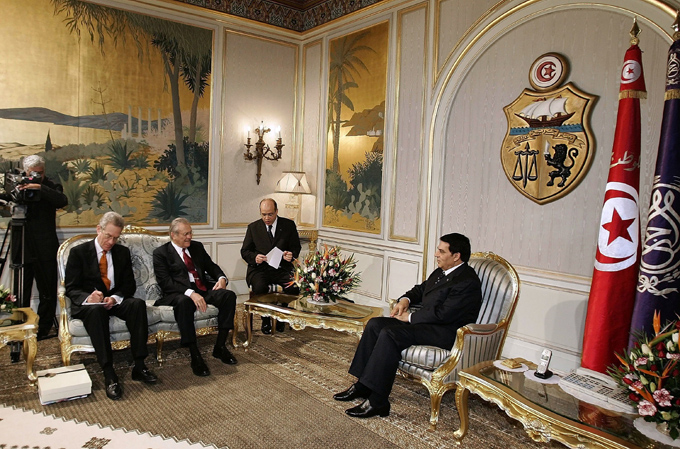

| Despite having a poor human rights record, Western countries – particularly the EU and the US – continue to have close relationships with Tunisia and remain silent on abuses there [GALLO/GETTY] |

Corruption, authoritarianism, repression. Not words that many would associate with the beautiful North African republic of Tunisia, a popular summer holiday destination for many Brits.

But the recent attempted suicide of a 26-year-old graduate, whose desperation at being mistreated by police led him to set himself on fire publicly outside a local government office, has sparked interest in this small, quiet country, long considered by the West to be a haven of stability and moderation and a rare “success story” in the region.

In nearly every field, Tunisia has been a model student of the West, embracing the hallmarks of modernity with zeal. Bourguiba, the country’s first president after its independence, sought to refashion Tunisian society along the French mould, from the aggressive secularisation of all public space and banning of the headscarf to introducing Enlightenment philosophy into high school curricula.

This modernisation process, it was assumed, would lead to a more advanced, prosperous and stable society freed of the chains of despotism and religion holding back the Arab world.

On the surface, the wave of protests that has swept Tunisia for the past two weeks were provoked by the dire situation of unemployed youth in the country, which has one of the highest literacy rates in the Arab world yet suffers from 30% youth unemployment. At least, this is how most international media have portrayed the situation.

Seething dissatisfaction

However, any discerning journalist who digs a little further can see that these protests are, like similar outbursts across the Arab world, the product of deep dissatisfaction at decades of sustained political repression, rampant corruption and routine silencing of all forms of political dissent.

Tunisia today exhibits all the symptoms of political decay that can be seen in surrounding Arab countries, with rising unemployment figures, widespread dissatisfaction and political unrest in the face of repeated extensions of so-called democratic mandates (President Ben Ali recently attempted to amend the Constitution to allow him a sixth term in office).

Any criticism of the President can lead to persecution and imprisonment, torture is routine and opposition parties are almost nonexistent. Not a single human rights monitoring group is allowed to operate legally and freely in the country.

Despite being a small country of just over 10 million, it has imprisoned more journalists than any other Arab country since 2000.

The plight of Tunisia demonstrates the fallacy of the US mantra of “stability over democracy”. A guiding principle of US and European policies in the region, this equation has turned out to be a false choice and an extremely dangerous assumption.

US and European governments have consistently privileged one limb of the “stability-democracy” equation, on the grounds that the repression of entire populations in the Arab world is but a small price to pay for the stable conditions necessary for us to benefit from the vast economic opportunities in the region and the counter-terrorism assistance they can give us.

However, the frequent outbreaks of political turmoil across the region demonstrate that stability and democracy are not part of a zero-sum game but two sides of the same coin. The US government has itself come to this conclusion, noting on the White House website in 2007 that “on 9/11, we realised that years of pursuing stability to promote peace left us with neither… The pre-9/11 status quo was dangerous and unacceptable”.

No will to apply pressure

Yet, despite full knowledge of the extent of despotism in the country (as revealed in the US cables from the US ambassador to the country), the US continues to ply the regime with financial, political and military support.

In seeking to maintain the corrosive status quo, America and Europe have contributed to creating unstable societies on the brink of implosion, leading to the disintegration of the equation altogether, while destroying any moral claims to be the legitimate expounders of human rights values in the process.

As Tunisia’s number one trading partner, the EU has ample room for influencing Ben Ali’s decision-making.

Under EU-Tunisia agreements, Tunisia promised to “strengthen democracy and political pluralism by the expansion of participation in political life and the embracing of all human rights and fundamental freedoms”.

None of these commitments have been respected by the Tunisian government, which instead froze EU subsidies to human rights NGOs under the European Initiative for Human Rights and Democracy and amended the penal code so as to criminalise civil society activity.

The EU’s own reports, such as the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument of 2007, recognise that “progress on political aspects such as freedom of expression or association has been very slow”.

But far from speaking out, the EU is currently in negotiations to upgrade relations and grant Tunisia “advanced-partner status”. This makes a mockery of the EU’s claims to be founded on respect for human rights, democracy and the rule of law, which consistently bow down before the priorities of trade, liberalisation and open markets.

The role of media

International media outlets also have a vital role to play in exposing the political turmoil and human suffering taking place in Tunisia and nearby countries.

It is striking that while the BBC displayed remarkable zeal in its coverage of demonstrations in Iran last year, with the human rights angle being explicit throughout its coverage, next to no mention has been made of the political upheaval in Tunisia (or in Egypt following the recent elections).

This, despite the fact that while Iran had a disputed election, election results in Tunisia are an entirely foregone conclusion, with results consistently around the 90% mark. Indeed, the Economist’s Democracy Index places Tunisia on a par with Iran for “political participation” (and behind Zimbabwe and China) while Freedom House ranks Tunisia below China, Iran and Russia as one of the worst places on earth for internet freedom.

While size and geostrategic significance of a country is undoubtedly important in determining the relative proportion of airtime and journalistic scrutiny devoted to its developments, one cannot help but observe that many media outlets have an unhealthy habit of falling in love with particular countries or issues for which it is easy to construct a clear-cut and racy narrative (Iran – anti-Western extremism; Zimbabwe – post-colonial “reverse racism”; Tibet/Burma – peace-loving opposition figures) while eschewing situations where a clear line of analysis does not so easily spring to mind.

Tunisia is just such a situation – a country with a strong women’s rights record yet no freedom of expression, a state with an avidly secularist, modernist outlook, but no toleration for dissent.

This makes it unattractive for many media outlets, who prefer soundbites that can capture the imagination of audiences, rather than real, in-depth analysis.

As the Tunisian government’s response to the protests show, autocratic regimes in the Arab world have only one stock solution to widespread political dissatisfaction – crackdown. This is often accompanied by promises of reform, which launch yet another futile cycle of half-hearted opening of political structures inevitably followed by another clampdown.

There is only so long this strategy will last in the face of growing demands for accountability, and a rising youth population clamouring for economic opportunities and political expression.

The familiar narratives of “stability vs democracy” and “progressive/secular/moderate vs anti-Western/extremist” no longer work. Western governments and international media would do well to pay closer attention and rethink their broken old clichés.

Intissar Kherigi is a Trainee Lawyer with a background in human rights. She has worked in the House of Lords, the United Nations in New York, and the European parliament in Brussels.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.