Beltway plumbing: Fixing DC leaks

Security leaks are commonplace across certain US government institutions, breeding unnecessary and harmful compromises.

|

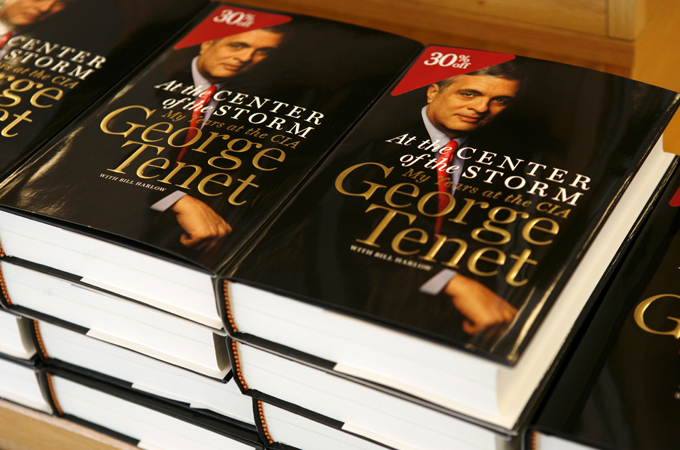

| Not even the 30 per cent discount quelled the collective disapproval (among the US Intelligence community) of the former CIA director, for the untimely publication of his memoir. An act that his British counterpart at MI6 would be unlikely to replicate [EPA] |

Lost in the recent excitement over news stories concerning various reported terrorist conspiracies (of indeterminate maturation) – allegedly involving European passport-holders being trained in the lawless wilds of Waziristan, and the subsequent hail of drone-carried missiles apparently intended to disrupt them – was an obscure comment from a British journalist speaking on a US radio broadcast.

He noted parenthetically that a number of European security officials had expressed displeasure over the string of anonymously-supplied revelations emanating from Washington concerning what was, after all, a European-centered threat, which they feared would induce the potential targets of their intelligence-gathering to go to ground and perhaps be lost to view, only to return, undetected, later.

Definitive differences

The journalist went on in this vein to express envy of his American counterparts who, he said, have such a rich trove of official sources, both serving and retired, concentrated within the narrow confines of Washington’s “beltway” ring-road, and quite willing to speak freely.

British security officials, he lamented, do not stay in London, but typically retire to the countryside, where they are hard to reach and in any case usually refuse all contact with the press.

Being one of those beltway chatterers myself, I have long noted the cultural differences with my former British colleagues, and have occasionally suffered their active disapproval, as they maintain a post-government code of omerta.

Lurking beneath this little matter of cultural eccentricities, however, is a serious problem.

As was clear to me while in government, and as has been reinforced since, the number of real secrets — defined as facts which, if revealed, would do serious harm to national, and indeed international security — is relatively small, and comprises a mere fraction of the enormous volume of classified material generated by the US government on any given day.

In the world of counter-terrorism, which garners a greatly disproportionate share of the press’s attention, such secrets are usually highly tactical, and fleeting: That drone missiles are striking targets in Waziristan is hardly a secret, and in any case difficult to hide; the target deck for an upcoming strike, or the subjects of a cooperative international investigation, however, are highly secret, and properly so.

Harmful compromise

Whether the most recent revelations reportedly decried by European security officials fall in this category is impossible for me to say. That legitimately harmful press revelations routinely emanate from Washington, however, is manifest: It was a significant problem for me while in government and it continues to be a recurrent problem today.

The effects of such leaks can be obvious and acute, or they can be more subtle: They can compromise ongoing intelligence operations on which lives literally depend, or they can slowly weaken and vitiate relationships with foreign intelligence partners who must carefully calculate the risks involved in sharing information with a US government which is seemingly incapable of keeping a secret.

The potential victims of US indiscretion are by no means limited to Americans. History has shown that the victims of a militant attack on a civilian target are far more likely to reside in the Muslim world than in the West, still less in the US.

Moreover, the damage caused by security leaks is often as needless as it is maddening. In nearly all cases, the legitimate public-policy justification for revelations of classified activities can be met without revealing the small details where the true secrets, and thus the potential harm, usually reside.

While in government, I was one of those apparently too-rare individuals who refused all unauthorized contact with the press. One of the things that has amazed me in my many interactions with members of the US press since then is how much they know about the inner workings of supposedly secret US organizations and programs, and which they do not reveal. While the relative, if inconsistent, responsibility and discretion of some members of the press may be laudable, the fact that one must rely on this discretion is a measure of the problem.

In defense of press freedom

Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. The strength of a liberal democratic system lies in its inherent checks and balances, which preclude any one individual, entity, interest group, or branch of government from amassing too much unalloyed power. The existence of a free press and its ability to cast light on hidden abuses and injustices is a vital part of that system, and where some elements of the press may distort the truth or mislead the public; there are others free to set the record straight.

In the realm of national security, however, there is currently in the US no effective countervailing force to check abuses of the public interest facilitated, if not perpetrated, by the press. Once a genuine national security-related secret is revealed, the harm has been done and cannot be undone. Yes, members of the established press often behave responsibly; and yes, news organizations will sometimes approach the government to discuss the pros and cons of a particular revelation before making the decision whether to go to press.

The problem, however, is that in the end, the decision lies entirely with them. Moreover, with the advent of the so-called “new media,” the competitive environment in which those decisions are made is becoming far less conducive to sober public-mindedness and discretion.

So great is the cultural power of the free-speech rights enshrined in the first amendment to the US constitution, however, that such discretionary powers as reside with law-enforcement agencies are almost never employed in this area. Legal proceedings against those who reveal classified information in the press, or even effective investigations to determine the identities of these informants, are rare indeed.

Exercising restraint

I should hasten to point out that I am not advocating that members of the press should themselves be held criminally liable for revealing classified information. That would clearly be going too far in restraining the press, and would never be accepted by Americans. Nor are Americans likely to accept the notion of “prior restraint,” under which media outlets are legally barred from revealing classified information which has been provided to them. A US “Official Secrets Act” will not fly. And yet, effective legal mechanisms to protect appropriately-classified information do exist, if only there were political will to employ them.

When in July 2003 a newspaper columnist revealed the name of a CIA operative, indicating that there had been a leak in violation of the Intelligence Identities Protection Act, US prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald launched an investigation in the course of which he hauled members of the press who had access to the leaked information before a grand jury to reveal – confidentially, in a closed legal proceeding — their sources.

|

| Valerie Plame, a victim (alongside those who worked with her) of a security leak. Her identity as a CIA operative was revealed in the political circus that pre-empted and lasted for a large duration of the Iraq war [EPA] |

The press admonition against revealing sources had no standing in a case where a crime had been committed. Some journalists sought and obtained “releases” of confidentiality from their sources, but in any case all eventually talked. In the end, a close adviser to Vice President Cheney was indicted, prosecuted, and convicted.

Again, the necessary mechanisms exist, provided there is political will to use them: Not to try to silence or stifle the press, but to insist that journalists, like the rest of us, cooperate in a legitimate legal process set in motion when a crime has clearly been committed.

Now, knowledgeable observers would object that if the threshold for criminality in the case of national-security leaks were simply that classified information were revealed by a government employee, that threshold would be far too low, as the government over-classifies all manner of information. And indeed, they would be right.

Just as journalists should not have the sole right to determine unilaterally whether information deemed injurious to public safety should nonetheless be revealed, so too government bureaucrats cannot be left to decide for themselves what information should be properly classified, and provided with unchecked legal powers to shield their decisions from scrutiny.

Prescription for a remedy

A solution to this problem could be easily found, however. Perhaps a panel of judges could be established to determine whether a piece of information which has been publicly divulged, and which the government claimed to have done serious harm to national security, does in fact meet the necessary criteria to be considered highly classified.

Having established thereby that an actual crime has been committed, the legal system would then be free to work in its normal manner to determine the perpetrator. The crime would reside not with the press, but with the public official officially charged under oath to protect the security of the nation and its people. Journalists, where appropriate, would simply be expected – as they already are, as a matter of law – to respond to official subpoenas for information when press accounts attributable to them have been the means by which a crime has been committed.

As a practical matter, given the constraints involved, the government would be highly unlikely to launch full-bore leak investigations except in clearly egregious cases. Among other things, the government is never eager to reveal classified information in a legal proceeding. However, the knowledge that an effective mechanism is in place to effect their discovery would have a salutary effect in forcing public officials to think twice before casually making genuinely damaging revelations to journalists.

Journalists, for their own part, would deliberate carefully to make sure that the important policy-relevant information about which they are usefully informing the public does not cross the line to do public harm by including details which place national security at risk while, not incidentally, making them liable to be called as witnesses to a crime.

The reform advocated here would be quite modest in scope, but could have a very positive practical effect, simply by introducing a positive tension into the system.

The bigger picture

The US likes to think of its legal and constitutional systems as models for others. Where press freedoms are concerned, however, repressive regimes are less likely to reform when the manifest dangers associated with the US culture of unfettered and unpunished national-security leaks serves as a disincentive. If the US seeks to inspire reform in the direction of greater freedom, it would do well to implement more thoroughly the system of checks and balances without which freedom is all too subject to abuse.

Robert Grenier is a retired, 27-year veteran of the CIA’s Clandestine Service. He was the director of the CIA’s Counter-Terrorism Centre from 2004 to 2006.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.