Going nuclear: Arab-Iranian fissure

The demonisation of Iran as a threat is all too common by Western and Arab states, based more on rhetoric than reality.

|

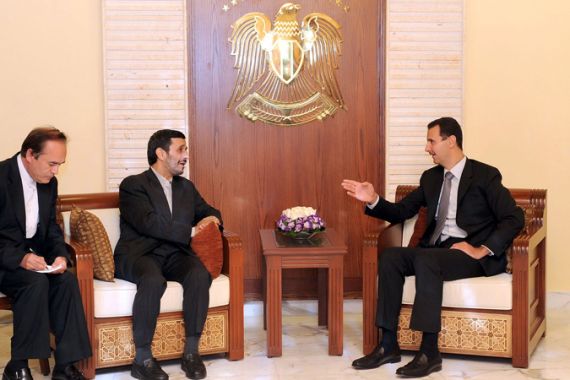

| Though under recent scrutiny, Iranian-Russian relations have prospered in the form of various co-operative pacts, a testament to Iranian diplomatic resilience [EPA] |

Schisms in Arab-Iranian relations litter their common history. None perhaps threatens calamity for both sides more than the fissure over Iran going nuclear. However, in Arab-Iranian relations the fusion of religion and politics is more of a quandary than the nuclear fusion Iranians seem to be seeking.

This is not a time for the Arab side to melt from the heat of Iran going nuclear. This is a time to put intellectual and political wisdom before irrational machinations against the ‘other.’

In the Mausoleum of Arab-Iranian History

The pages of some Arab dailies have for over a year been drumming up public hysteria over the Iranian nuclear project. Many opinion formulators such as on the pages of ‘Al-Sharq Al-Awsat’ have been itching for a war with Iran for some time. By deploying a psychology of fear and ‘demonization’, Arab war-mongers impel their audiences toward a stand-or-die attitude in the defence of entrenched and often mindless positions.

To this end, some hawkish voices risk mortgaging Arab, Middle Eastern and World futures to yet a new war perhaps through an Israeli pre-emptive strike against Iranian nuclear installations. As if Iran, Israel, the Arab world and Western countries need another conflict! The politics of Armageddon must not be viewed as the healing ointment for relieving the problem of Iran going nuclear.

Seeing things through a Sunni-Shiite lens or an Arab-Persian prism would only bring to the fore what has been seen for centuries. The first schism (or fitnah, 661 AD) that divided the house of Islam into Sunnis and Shiites. Also seen, to the point of exaggeration, is the mutual enmity and subsequent fissure. Deeply etched in Persian memory is the Arab-Muslim conquest that prevailed over the Persian and Zoroastrian Sassanid Empire in the mid-seventh-century AD.

However, the Persian nation’s line of defence became cultural and epistemological, fending off ‘Arabization,’ The Arab literati are well aware of their debt to Persian Muslim philosophy, architecture, arts and administration. As do the ‘grammarati,’ the debt to the remarkable Persian scholar Sibawayh who codified Arabic grammar in the mid-800s.

Iran going Nuclear

It was the Shah and not the Islamic republic that initiated the quest for a nuclear project in the mid-1970s. The road to nuclear science know-how, human resources and capabilities amassed today has been long, arduous and challenging. Since 1979, following Imam Khomeini’s Islamic revolution, Iran has been surviving against all odds.

Partly, this is owed to Iranian astuteness, secrecy, and intelligent diplomacy, which has set out to diversify economic partnerships with the outside world, in the face of many restrictive sanctions.

Partly, Iranian tenacity and patience which reflects a cultural trait of a meticulous and elaborate carpet-weaving work ethic. This steadfastness is an admirable fixture of the Iranian persona. Note the many crises that have marred Iranian-Western relations since the late 1970s. Each presented Iran’s Islamic revolution and its leaders with challenging obstacles.

Thus far Iranians seem to have passed each with flying colours. True the latest sanctions are debilitating and are starting to bite inside Iran. However, the fact remains, that as the world shuts the doors of trade and banking in the face of the Islamic republic, the more Iranians search deep into their local resourcefulness to surpass the tests thrown at them.

Politically, the day Baghdad was sacked in March 2003, the late Imam Khomeini’s revolutionaries had their revenge on Iraq and Sunni Arabs who helped fund a costly and damaging war to both Arabs and Iranians. March 2003 was the real date of the Islamic Republic’s triumph in the region. Iran has been the biggest beneficiary of the change of regime in Iraq.

Technologically, Iran today boasts more than 5000 scientists, making the country’s nuclear programme largely an indigenous achievement. Diplomatically, A series of stand-offs beginning with the US freeze of assets following the US embassy hostage crisis (in 1979-80 and beyond) through Martin Indyk’s misguided 1993 ‘dual containment,’ and up to the cumulative regime of sanctions have not weakened Iranian resolve on the path to going nuclear.

Iranians seem to be astute diplomatic players on the big stage of ‘high’ politics. They know how to defend their interests, define what they are, and pursue them with skill, guile, cunning, and resolve.

By contrast, the pan-Arab sub-system in the surrounding region has been gradually crumbling. The Iranians have been busy engineering not only the building blocks of nuclear energy, but also a network of ties, liaisons, and relations that collectively serve and safeguard Iranian interests.

Iranian resolve

Their tentacles spread from Moscow to Gaza. One notes in amazement how whilst Arab regimes are easy targets of international interventionism, the Iranians are exactly the opposite. By war, international courts, UN Security Council sanctions, big power play and diplomacy, Arab states seem to be more amenable to control. Iraq, Libya, Sudan, Syria, and Lebanon are all one by one tamed and kept in check.

The easy dismissal of Iran in some Arab quarters as simply the bedrock of Shiite heretics is facile. The Iranian threat, factual or imagined, is not going to be resolved through the emotive deployment of the Shiite-Sunni, us-them rhetoric and ‘clash.’

The means of Iranian self-regeneration are deeply rooted in an ingenious culture and civilisation. It is wrong to assume that ingredients of Iranian steadfastness and astuteness are solely embedded in the treatises of Shiite doctors in the thousands of seminaries dotting this vast land or in the fables of Karbala and the martyrdom of Hussein (680 AD).

Iran’s own self-understanding and self-belief derive meaning, meaningfulness, identity, and self-empowering creativity from both monotheistic as well as Zoroastrian and even animist sources. It is wrong to conceive of Iran as a fixed, single and mono-cultural entity. It is this plurality that enriches Iran and equips it with the means to stand up to the world, and, seemingly, succeed.

Iranians celebrate the martyrdom of Hussein but also with equal zeal and passion celebrate nature, spring, and flowers – for example Sizdah Bedar and Nowruz. Isfahan is their ‘nesf-e-jahan,’ half the word, Shah Abbas’s masterpiece city of beauty and learning tells another story of how Iranians see their place in the world. In Hafez [1317-1390] they have a quasi Persian Prophet who celebrates Islam and the union with the divine through beautiful prose and poetry.

Reality mirroring mythology

In mythology there are the threads of continuity with which Iranians weave the tapestry of cultural, political and religious uniqueness. Even Khomeini’s seminal religious thinking is not bereft of Zoroastrian dualism. His division of the world into oppressors or supremacists (mustakbirun) and oppressed or down-tordden (mustadh’afun) mirrors the battle between good and evil not only between Qur’anic Godly angels and Satan, but also between Zoroastrian deities.

The battle between good and evil is embodied in the twin brothers: Ahura Amazda the God of creation, truth and light. Ahriman, on the opposite side, is the God of darkness and evil. It would be glib to dismiss this mythological complexity that feeds into the cosmic identity and political culture of an important Middle Eastern state. Iran views itself as endowed with a similar missionary role and a cosmic duty that combines so many elements, some inspired by Hussein’s fight for justice as well as Ahura Mazda’s resistance against darkness.

Whether it is envy or threat that feeds into Arab fear of Iran, there is no way out of understanding Iran instead of reducing it into an emotive adversary whose behaviour is solely shaped by Shiite doctrine. Arabs themselves possessed but seem largely to have lost the plural sources of self-regeneration and self-belief. That is not an Iranian problem. That is an Arab problem.

Dr Larbi Sadiki is a Senior Lecturer in Middle East Politics at the University of Exeter, and author of Arab Democratisation: Elections without Democracy (Oxford University Press, 2009) and The Search for Arab Democracy: Discourses and Counter-Discourses (Columbia University Press, 2004), forthcoming Hamas and the Political Process (2011).

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.