Assad returns to familiar themes in speech

The Syrian president was largely unapologetic for recent violence and offered only vague promises of reform.

There was little in Bashar al-Assad’s speech on Monday that Syrians have not heard before.

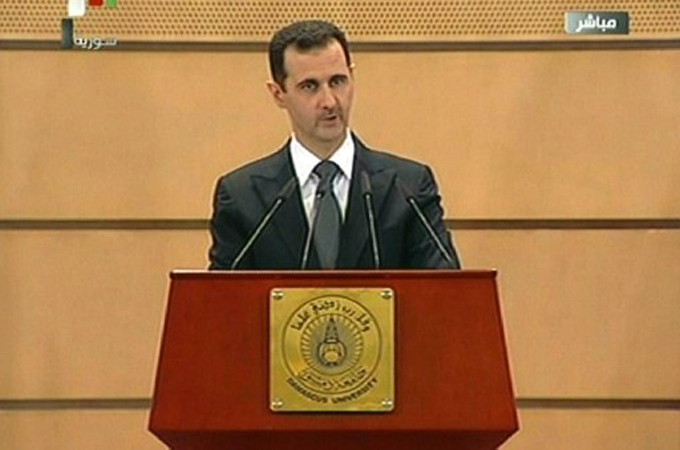

The president’s 75-minute address to an audience at Damascus University echoed the themes he struck in two previous televised addresses. He opened with a long discussion of the “foreign conspiracies” against Syria, and justified the army’s use of force against protesters as the “only option left.”

He offered little by way of reforms, promising only a series of committees and “national dialogues” to address various issues – political reform, the economy and the constitution, among others.

His hour-long address to the Syrian parliament in late March blamed the protests on foreign conspirators; he promised reforms, but offered few specifics. Two weeks later, Assad spoke to his newly-appointed cabinet, pledging to end the country’s emergency law and tackle unemployment. Since then, Assad has been largely silent.

“I did not want to speak until I had something to say,” Assad said.

While his words were similar, though, his body language was different. Gone was the jocular president who leaned into the podium and cracked jokes with the parliament; the Assad who spoke on Monday was more hesitant, hanging back from the microphones, pausing frequently to cough or clear his throat.

It was a deeply technocratic speech, focused on committees and bureaucratic changes – at one point, Assad spoke about the need for various government agencies to co-operate better – rather than concrete reforms.

“The national dialogue authority will be tasked with consulting with different groups to reach the correct formula to design a reform plan,” Assad said, for example, striking what might seem an oddly detached tone given the current unrest in Syria.

The ‘black period’

Assad was largely unapologetic about the crackdown which has left hundreds dead, particularly the recent violence in northern Syria, centered around the town of Jisr al-Shughur.

The Syrian government has accused “armed groups” in that town of killing 120 members of the security forces, a claim which cannot be verified or disproved. Assad repeated that claim in his speech, and said the attacks were carried out by a “minority … with a medieval mindset.”

More than 10,500 refugees have fled violence in northern Syria this month, according to Turkish officials [Reuters]

More than 10,500 refugees have fled violence in northern Syria this month, according to Turkish officials [Reuters]“They had very advanced weapons and means of communication,” he said. “[This will] derail the reform process and bring grave repercussions on our society. What is happening today is not related to reform or development, it is mere vandalism.”

His language seemed to be an oblique reference to the Muslim Brotherhood, the banned opposition group-in-exile which has thrown its support behind protests. The group has had little influence in Syria since 1982, when Hafez al-Assad, the current president’s father, bombarded the city of Hama to quell a Brotherhood revolt. Tens of thousands were killed.

Assad mentioned the Brotherhood again later, when he accused some Syrian protesters of being “destructive elements.”

“Some of these demands are from the period of confrontation with the Muslim Brotherhood, the black period,” Assad said. “We should not continue to live in a black period.”

Assad did offer his condolences to families who have lost loved ones during this year’s unrest, but said nothing about punishing officers or soldiers implicated in human rights abuses.

“They are spreading chaos in the name of freedom,” Assad said of the protesters in Jisr al-Shughur. “The use of force was the only option left… in some cases peaceful demonstrations were used as a cover, where armed infiltrators were hiding.”

‘Depression and fear’

Assad spent little time discussing the economy, one of the deepest grievances in Syria. The country has posted growth rates of 4 to 5 per cent over the last three years, largely thanks to increased oil and gas exports. But corruption and a heavily state-directed economy have meant the benefits of that growth are not widely shared.

Assad said he directed the government to boost employment, and to fix the damage caused by months of protests. (The Syrian government has not publicly estimated the cost of the protests, both direct and indirect, to the economy.)

He also stressed the need to restore confidence in Syria’s economy, warning that its “collapse” would have serious consequences.

“The most dangerous thing we face in the next stage is the weakness or collapse of the Syrian economy, and a large part of the problem is psychological,” Assad said. “We cannot allow depression and fear to defeat us.”

But he offered no specific proposals for economic reform, short of calling for a national dialogue on the shape of Syria’s future economy.

He did touch on corruption – again, promising a committee would deal with it.

“Corruption has left a great deal of sorrow. Corruption is enough to undermine any country,” Assad said. “It is the result of favoritism and nepotism.”

Left unspoken was the name of Rami Makhlouf, one of the country’s wealthiest businessmen, who announced last week that he was quitting business and donating some of his investments to charity.

Makhlouf is a widely reviled figure in Syria, a symbol of the nepotism at the intersection of business and politics: He is the president’s cousin, and that tie to the ruling family has given him monopolies in a number of businesses, including telecommunications, real estate and construction.