Belfast’s psychological barriers

Separation continues to define Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland.

|

| There are thought to be 41 deliberate barriers across Belfast today |

As part of its Walls of Shame series, Al Jazeera explores the physical and psychological barriers that continue to separate Belfast’s Catholic and Protestant communities.

The modern history of Northern Ireland has been dominated by one thing – the Troubles – a violent, bitter conflict, both political and religious, between the predominantly Catholic Nationalists or Republicans and the mainly Protestant Unionists.

But in 1998, Northern Ireland’s political parties signed up to the Good Friday Agreement, breaking three decades of deadlock.

A power-sharing assembly was established, paving the way for the withdrawal of British troops and the disbanding of paramilitary groups.

After many false starts, the assembly assumed its full powers in May 2007, and the sworn enemies of yesterday: Unionist leader Ian Paisley, and the Republican leader Martin McGuiness became first minister and deputy first minister.

But what Northern Ireland has now is not so much peace as an absence of conflict.

Far from disappearing, the walls have grown and instead of reconciliation, there is partition – an ill-tempered stalemate of separate identities and separated lives.

Segregation

Neil Jarman from the Institute for Conflict Research says: “There’s a huge amount of segregation in daily lives, particularly within working class communities. Kids go to school in different schooling, Catholic schooling or Protestant schooling, they would just not mix.

“That’s not a consequence of the walls, the segregation and division were there before the walls, they just fed into that, and the further segregation continued from that. So we’re now in a situation where there’s more segregation after 13 years of the peace process than there was during the conflict.”

The first of the so-called peace lines began as a length of barbed wire, rolled out by the British army to separate the warring communities in 1969. From then on, they became more common and more complex. Today there are thought to be 41 deliberate barriers across Belfast.

“We estimate that about half of all the barriers have either been built anew or have been extended or enlarged or heightened in some way over the last ten years, over the course of the peace process,” Jarman says.

‘Us and them’

The most notorious barrier was the one between the warring communities of Protestant Shankill and Catholic Falls Road.

But the flashpoint of recent years has been the wall that separates the Short Strand, an isolated Catholic enclave in east Belfast, from the surrounding Protestant areas.

|

| Sean McVey lives in an isolated Catholic enclave surrounded by Protestant communities |

In 2002 it was the scene of the worst riots in the city since the start of the peace process.

Sean McVey, a Catholic who lives with his family in the shadow of the Short Strands wall, recalls the 2002 riots.

“The wall was low at the time. The houses where we live, the whole roofs, every window, upstairs, downstairs were smashed, destroyed.”

Greta Abbot lives with her family on Cluan Place on the Protestant side of the wall.

“I actually moved in during the troubles in 2002, because a lot of the people in the area had children, were elderly and were put out by the people next door and we needed people to move in here who weren’t afraid of living here, so I upped sticks and I moved in,” she says.

The wall between the two communities has become the focal point of this conflict. This is not a spat between neighbours, but the battle-line of a war between two traditions, two denominations, where an ‘us and them’ mentality still exists.

‘Walls of prejudice’

Greta says: “They nearly killed us. What can we do? The police don’t stand up for us. And we did send for people. They came in, they attacked them back, they went home. That’s it. Finished.

“They have to be shown that we’re not by ourselves. That other people are there ready to come in and protect us.”

It is the absence of trust – dating back centuries – that has kept the walls of Belfast in place.

McVey says: “It’s not the first time that walls have been built in Ireland. They’ve been there for 400 years.

“And walls aren’t just built with brick and mortar. They can be built with legislation and laws and prejudice you know.

“I think we have to take down the walls of prejudice first before you can take down the physical walls.”

Parades

Marching season in Belfast is either a celebration or provocation, depending which side you are on.

|

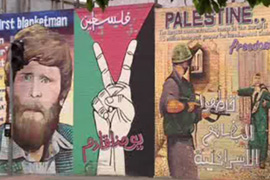

| Wall murals are used as a way of marking territory |

For the marchers, the victory of the Protestant King William over the Irish Catholics in 1690 is at the very core of their conviction that they are, and will always remain, part of the United Kingdom.

Ian Paisley Jnr, the son of the Unionist leader and first minister, says: “Parading is very much a way of life, it is a cultural expression of a person’s identity, especially from the Protestant community.

“And it is a celebration of a battle that took place over 300 years ago, the Boyne, and celebration is an expression of freedom, expression of liberty, and expression of fraternity.”

But from a catholic perspective, the drums and banners are triumphalist gestures calculated to keep old wounds open.

Jennifer McCann, a Sinn Féin member of the Northern Ireland assembly, says: “You have to understand, we’re only just coming out of a conflict situation.

“There are people who are living in those areas that have been murdered by loyalist paramilitaries and I think that it’s insulting for them to have to watch an Orange parade walk down that is holding banners of loyalist paramilitaries for instance; you know it’s very hard for residents to take that.”

On both sides, the past is ever present – whether it is the Battle of the Boyne more than three centuries ago or a riot within the last decade.

For those on the frontline, time has not been a healer here. The conflict has merely found other means of expression.

Officially the conflict in Northern Ireland is over, but more than a decade into the peace process many of the sectarian rituals live on as a means of distinguishing, reinforcing and boasting.

Every July 12, towering bonfires are lit by Protestants to mark their famous victory over the Catholics in 1690. The crowds cheer when the hate symbols – chiefly Irish flags – go up in flames.

“McVey says: “It was always like a traditional thing with the loyalists, right back to the 60s when I was young, the putting up of flags to mark their territory. You’re here, you’re in loyalist territory, you know. There was always that there. When I was young in the 60s, it was illegal to fly a tri-colour [Irish flag]; you could be jailed.”

‘Writing on the wall’

But the symbolism does not always take the form of flag-waving.

Some of the “writing on the walls” that have divided Northern Ireland have been raised beyond crude propaganda to an art form with its roots in another country and another conflict.

|

| Some of Danny Devenny’s murals were inspired by the Palestinian/Israeli conflict |

Danny Devenny is a Republican muralist who honed his talent while serving time in the Maze prison.

Standing in front of one of his murals, he says: “I remember watching funerals of Palestinian young people killed in the West Bank and at their funerals they would carry pictures of these people, and I thought I would like to know who that person is – what they represented, why did they die, why was such a young life taken?

“And I think it’s also transmitted into these type of murals. When people look at these faces – young men, young women – they ask the question: Why, what was it about?”

Devenny is now involved in the unlikeliest of artistic collaborations. He has paired up with Mark Ervine, the son of one of Northern Ireland’s best-known Protestant loyalist leaders.

The two men, who in the past chronicled the troubles – each on his own side of the wall – have come together to bring a new message to the city.

In a Northern Ireland, where separation has generally become more entrenched since the end of hostilities, it is a remarkable act of collaboration and hope.

‘Sign of the times’

Ervine says: “It’s absolutely a sign of the times we are living in now because this wouldn’t have been possible 10 or 15 years ago.”

While Devenney says: “In my community, the walls were used to deal with issues that no one else would focus on. And basically the images you see on our walls reflected the feelings within our communities. That’s what we were doing. We were vehicles for fear or anger or frustration within our communities.”

Ervinne says that the walls in his community were used by different groups to mark territory.

Now the two men are determined to use the murals as a force for unity rather than division.

“We met accidentally but there’s always so many barriers holding people back and if those can be broken down, then my kids, my grandkids can meet up with people from Mark’s community and they’ll find the same. I think that’s the key,” Devenney says.

“And once those barriers, once those walls start falling.”

Ervinne says: “Its trying to change people’s mind sets because that’s where the barriers exist, in the mind.”

The lesson of Northern Ireland is that dismantling a wall is far harder than erecting it. Walls are indicative not just of division but of mistrust.

In Belfast, the day the walls come down is still a long way off.