Cambodians seek closure from trial

Survivors hope Khmer Rouge tribunal will help heal wounds of country’s brutal past.

|

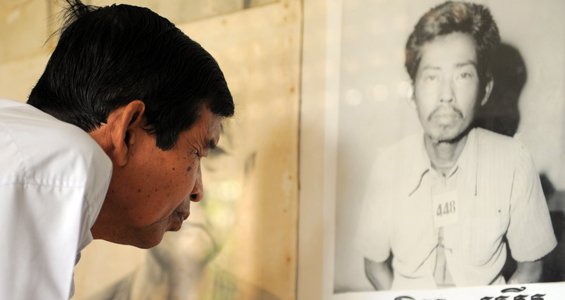

| Many Cambodians hope the tribunals will deliver justice to those killed by the Khmer Rouge [AFP] |

Three decades after the fall of the Khmer Rouge from power, a joint United Nations-Cambodian tribunal has finally begun the first trial of former regime officials.

Based in the outskirts of capital Phnom Penh, the court was established in 2006 to indict senior leaders of the Khmer Rouge and bring some accountability for the 1.7 million Cambodians who died under the regime.

| IN DEPTH |

|

Videos: Survivors’ stories: |

Many pundits had forecast that the tribunal would never happen, following years of delays and wrangling.

In the years following the Vietnamese invasion in 1979 that forced the Khmer Rouge from power, Western governments blocked attempts to organise an international effort to prosecute the perpetrators.

Many, including the US and Britain, even supported a Khmer Rouge-led coalition and backed the group’s guerrilla war against Vietnamese troops defending the new Phnom Penh government.

The first to go before the joint panel of Cambodian and international judges was Kaing Guek Eav – also known as Duch – the former director of the S21 interrogation centre where more than 14,000 prisoners were detained, tortured and executed.

Four other former senior regime officials are expected to go before the court in 2010.

|

| The tribunal has been closely followed by survivors of the Khmer Rouge [AFP] |

When Duch’s trial began in late March, live coverage of the proceedings was followed closely by hundreds of thousands of Cambodians on television and radio.

“We have been waiting for a long time. Now our hopes have become a reality,” Thun Saray, chairman of Cambodian human rights group ADHOC and a veteran activist, told Al Jazeera.

The failure to punish or account for the biggest crimes in the country’s history means that many Cambodians today have little respect for the law, he says.

Like many Cambodians over the age of 40, painter Hen Sophal vividly remembers the horrors of forced labour, pitiful rations and the constant fear of death under the Khmer Rouge regime.

He had all but given up hope of ever seeing any justice.

“I didn’t expect that it would happen. But even after 30 years it is not too late,” he says.

Culture of violence

The three decades without any closure on the national trauma has left Cambodia’s deep scars open and unhealed, undermining the ethical foundations of normal society and spawning a culture of violence, lawlessness and impunity.

|

| An estimated 1.7 million people died during the Khmer Rouge’s rule over Cambodia [AFP] |

“The Khmer Rouge shadow looms over Cambodia to this day,” says Hen Sophal. “There is still a Khmer Rouge influence in Cambodian society, still lots of violence and lack of human respect.”

He is also worried about the slow pace of progress.

“I am concerned about many delays because the Khmer Rouge leaders are getting older and could die before their trial starts.”

The start of the trial, he hopes, “can lessen the suffering of the victims and provide lessons for the young generation”.

Sin Putheary is a recent graduate from Phnom Penh University who now works for Youth for Peace, an NGO attempting to bring information about the tribunal to people in the countryside.

Even today, she says, many accused murderers brought before Cambodian courts see no reason why they should be punished.

Citing police reports, she quotes one suspect telling investigators recently: “I only killed one person, but Khmer Rouge leaders killed so many and they were never punished.”

|

“The tribunal is important step to ending the culture of impunity” Mouen Chean Nariddh, |

Mouen Chean Nariddh, a local writer and journalist, has been making the same link for years.

“The tribunal is an important step to ending the culture of impunity,” he told Al Jazeera, adding that he hopes the trials will act as a model and help establish the foundations of a proper justice system for Cambodia.

Local courts are known to be mired in corruption but, with the eyes of so many Cambodians and the international media on the Khmer Rouge tribunal, he notes that the Cambodian lawyers “show much more integrity working in the tribunal”.

“Cambodian judges and lawyers will use the tribunal model, and transfer from the KRT the example to a fair trial and rights of the accused to the local courts.”

Collective grief

Another common theme is that by bringing a sense of closure to the darkest chapter of Cambodian history, the tribunal will help to address the collective grief of a nation.

On the opening day of Duch’s trial, all 500 seats in the public gallery were taken and 80 per cent were Cambodians.

But far from everyone is gripped by the most important trial of all time for Cambodians.

More than two thirds of the population is under the age of 30 and have no recollection of life under the Khmer Rouge.

|

| Duch, the former Khmer Rouge prison chief, is the first to face the tribunal [AFP] |

With little or no teaching of recent history in Cambodia’s schools, most Cambodian youth have little knowledge of Pol Pot’s regime or its alleged crimes.

The single nationwide survey about the tribunal, published by the University of California, showed that more than a third of respondents had no knowledge of the trials.

That is not the case with Nong Visoth, who works as a travel consultant in Phnom Penh. He lost 15 relatives on his mother’s side of the family to the Khmer Rouge.

Closely following the tribunal every day, he says the tribunal is important to his family “because it can reduce our pain and suffering”.

But for him and many other survivors of the Khmer Rouge, the most pressing concern is that real justice may still be thwarted – not by political meddling, but by the simple passage of time.

Pol Pot, the former supreme leader of the regime, died more than 10 years ago.

His deputy, Nuon Chea, and the regime’s foreign minister, Ieng Sary, are now both in their 80s and in poor health.

“I worry they will die before the verdict, before they are sentenced,” says Nong Visoth.

“If the leaders die before justice, before their trial is completed, Cambodian people will still suffer for the rest of their lives.”