People crossing into Latvia allege torture by security services

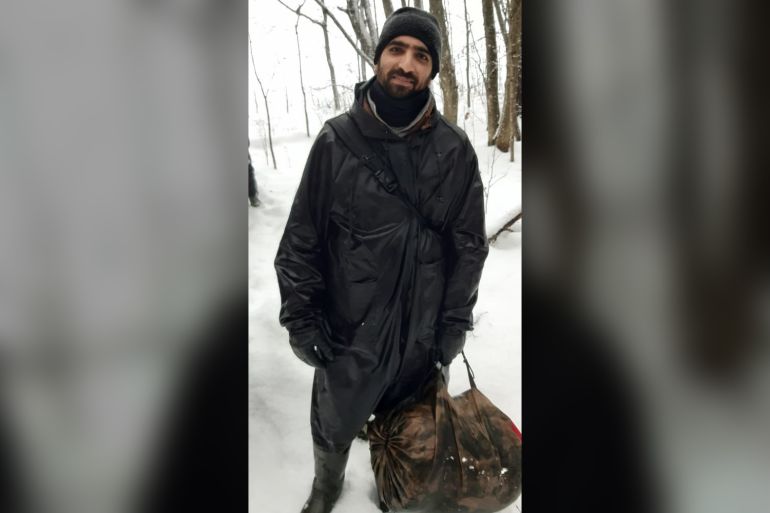

A Syrian refugee who fled from Belarus says border guards put out cigarettes on his war wounds.

Herne, Germany – For Abdalrahman Kiwan, who hails from the town of Tafas just north of Syria’s ancient city of Dara’a, walking has been painful for years.

In 2014, his left leg was injured in a Syrian government air attack that hit his home and killed several of his family members, and to this day, the shrapnel injury causes the pain in his leg to fluctuate between numbness and agony when exposed to the cold for long periods of time.

As a family man with a wife and two children, Kiwan, 28, is mild-mannered and polite, but not immune to light banter when the moment calls for it.

Even in the most challenging circumstances, he can put on a smile and push forward.

Years after his injury though, Kiwan’s ability to withstand hardship was pushed to the limit when the pain in his wounds was reignited, this time allegedly by members of Latvia’s security forces in the country’s border zone.

Late last year, Kiwan spent weeks trekking through cold, swamp-ridden forests that run along Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia’s borders with Belarus in his bid to find shelter in Europe.

Kiwan had been forced to leave his family behind in Syria in early 2022 as the government of Bashar al-Assad continued its crackdown on people who, like him, had worked with internationally-funded civil society organisations in the Dara’a region.

To try to secure a better life for his family in Europe, Kiwan left for Lebanon, from where he embarked on the perilous migration route through Belarus.

After arriving in the country via Russia in October 2022, he embarked on his journey with a group of five people, which soon grew to include 10, and said he paid smugglers $5,000 to get him from Belarus into Latvia.

At one point in December 2022, he says, when he was apprehended by Latvian border guards after crossing into Latvian territory to meet a smuggler on the other side, he lost consciousness in a tent set up by Latvian authorities in the forest as his health suffered. He said he was held along with a group of Iranian migrants and was awoken by splashes of cold water and punches to his legs, stomach, and waist.

He was then taken to another tent, one which Kiwan claims was overseen by six masked members of Latvia’s security forces, whom he could not definitively identify as either Latvian State Border Guard members or regular police officers.

Once there, one of them asked him why Kiwan was in such a poor state of health.

“I told him I had injuries from the war in Syria, and they were worsened by the cold,” Kiwan said.

After the security personnel commanded him to tell them where he was injured, he showed them where pieces of shrapnel had been buried in his leg nearly nine years before.

“Five of them held me down to the ground, and a sixth person extinguished a cigarette in the places of my war injuries on my left leg,” Kiwan said.

“They told me that if they heard my voice or anything from me ever again, they would kill me.”

Kiwan’s testimony fits into an emerging pattern of abuse documented by international organisations that Latvian forces have allegedly committed against migrants and refugees crossing from Belarus, whose government has been accused of manufacturing a refugee crisis along the European Union’s borders starting in 2021.

The country of President Alexander Lukashenko, the closest ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, was found to have encouraged refugees and migrants to flee, in an attempt, European officials said, to destabilise Western powers.

‘I shake with fear’

In photos Kiwan sent to Al Jazeera English, five red burn marks are visible on his thigh where the Latvian guards allegedly burned him.

He recounted how, earlier in December shortly before the cigarette burns, another masked member of Latvian security forces used a device to give him electroshock three times on his injured leg and once on the left side of his waist.

“The shock to my waist, I felt it throughout my whole body,” Kiwan said. “It set off an explosion in my head.”

Although the Latvian government has repeatedly denied such accusations in the past, personal accounts like Kiwan’s, coupled with physical evidence of his injuries, add further weight to the accusations of arbitrary violence by Latvian forces.

After multiple unsuccessful attempts to enter Poland and Lithuania, Kiwan spent one month in the Latvian border zone starting in early December 2022.

He said he was also subject to verbal abuse and repeated beatings, some carried out in the tent area in the forest.

“I don’t like returning to this experience,” Kiwan said. “I see inside myself that I shake with fear thinking about the abuse of the masked men in the tents.”

At one point, Kiwan said, he spent seven days in a closed holding centre for migrants, before eventually making it to an open camp in Latvia. From there, he escaped with a smuggler to Germany by car.

In the wake of his ordeal, Kiwan spoke to Al Jazeera from a refugee and migrant shelter in Herne, Germany, where he has been living since late January 2023.

Another resident in the German shelter, Hassan (not his real name), a 31-year-old former nurse and human rights volunteer who also fled Syria’s Dara’a region in 2022, accompanied Kiwan for part of the journey.

Although they had never met in Syria, Hassan recounted how the pair had happened upon each other while crisscrossing the forested Belarusian border zone.

Hassan instantly knew Kiwan was a fellow Dara’a native after recognising his unique Arabic accent.

Although eventually separated after making it into Latvia, Hassan reported similar experiences to Kiwan at the hands of Latvia’s border guards.

After they apprehended him in December 2022 in a rural area along the northeastern portion of Latvia’s border with Belarus, border guards allegedly forced him and others in his group into a car. He said they punched him in his mouth, jaw, and shoulder, and gave a middle-aged man in the group a black eye.

They repeatedly slapped another member of the group and carried out degrading, humiliating acts, he said.

“A member [of Latvia’s security services] was in the car, and he did things like passing gas into the face of my friend,” said Hassan.

The Syrians’ accounts dovetail with claims by Amnesty International, which in October 2022 documented allegations of electric shock torture, beatings in tents, and other abuse.

Ieva Raubiško, advocacy officer for the Latvian NGO I Want to Help Refugees, said her group heard similar accounts during its work on the Latvian border, and said the aim was “to scare, to make people not want to return [to Latvia], although they most often have no choice, because Belarusian services are also pushing them back”.

Raubiško said those working in the tents area appeared to be a special unit of the border guard, while other services active in the border area included regular border guards and special units of the state police.

Since August 2021, Latvia has maintained a state of emergency along its border with Belarus, which has allowed not only the State Border Guard but also members of the military and the state police, to forcibly return irregular migrants and refugees back across the border into Belarus.

NGOs and humanitarian groups say they have been unable to gain requisite access to detention centres to fulfil their functions, even outside the border zone.

The Latvian government, which previously called the Amnesty report “bogus”, continues to deny wrongdoing.

In a statement sent to Al Jazeera, a State Border Guard spokesperson denied allegations that Latvia had engaged in physical force, and claimed that there have been cases in which refugees and migrants who crossed into Latvia “lie[d] and [gave] false information and testimony in order to get a benefit for themselves”.

Meanwhile, as the door remains closed to migrants and refugees trying to cross its border with Belarus, Latvia has welcomed more than 35,000 Ukrainian refugees since Russia’s invasion began.

“When you arrive to any border, and the border guards catch you, they ask you ‘Are you Ukrainian?’” Hassan said. “When you say no, their smile disappears.”

According to Latvia’s interior ministry, the number of people trying to cross into the country from Belarus has increased, with 1,053 reported crossings taking place in December 2022 alone. This represents a significant jump compared with November’s 429 reported crossings.

Civil society groups say that accessing the border zone remains difficult and claim they are also being targeted.

After attempting to meet a group of Syrians near the border in January, Raubiško was notified that criminal proceedings had been launched against her “namely for moving persons across the border” – charges she denies.

Experts say the lack of third-party oversight in the border zone has made it difficult to obtain irrefutable proof of torture and ill-treatment, making legal challenges difficult.

“It’s objectively hard to prove such cases,” said Edgars Oļševskis, a lawyer at the Latvian Center for Human Rights. “It will take years to restore justice and to provide the necessary compensation for the persons who have been treated badly.”

Kiwan said he did not report his treatment to Latvian police or other state authorities at the time out of fear of reprisals.

But he now intends to file a complaint with the Latvian government, and if this fails, he wants to take his case up with European courts.

To this day, he said, he cannot fathom why he and others like him were treated with such disdain.

“Whoever goes to Latvia, his fate is honestly unknown: death or return to Belarus,” he said. “Why are refugees expelled and shocked with electricity? We are people who left for a dignified life, to ask for safety and security, from the tyranny of the Syrian regime. We are people who have dignity and pride in ourselves. So why all this torment?”