Italy elections: Campaigning is over. Now what?

Italians will vote on Sunday to elect a new parliament with a right-wing coalition tipped to form a solid majority.

Rome, Italy – A feeling of excitement filled the air in Piazza del Popolo, one of the iconic squares of Rome, when far-right leader Giorgia Meloni gave her last campaign speech in the Italian capital before Sunday’s election.

“We are the real majority of the country,” she told the cheering crowd on Thursday, dressed in all white and exuding confidence.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsElections: Why fascism still has a hold on Italy

Will a right-wing win push Italy towards Russia?

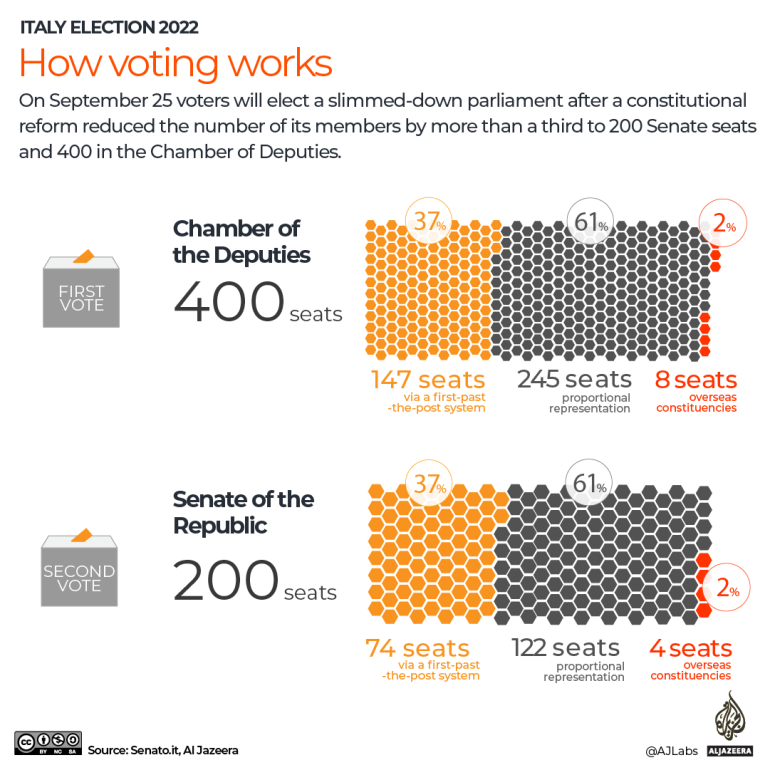

Who is running, how does voting work in Italy’s election?

Opinion polls agree. One in every four Italians plans to vote for Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party, according to the last survey published before a pre-election ban on September 10. This would put Meloni on track to becoming Italy’s first ever female prime minister at the head of a right-wing coalition that includes anti-immigration populist Matteo Salvini and octogenarian media tycoon Silvio Berlusconi.

The snap election comes after a chaotic summer campaign triggered by the collapse in July of the national unity government of Prime Minister Mario Draghi – an unelected technocrat and formerly Europe’s most powerful central banker – that represented to many a rare moment of calm in Italy’s stormy politics.

The last election was five years ago, but since then there have been three different governments. This time, voters will cast ballots amid a biting energy crisis, widespread disillusionment about their politicians’ visions, and questions over the country’s future stance towards the European Union.

Energy crunch

With supplies of Russian gas running low as the war in Ukraine drags on, Italians are bracing themselves for skyrocketing heating bills this winter.

The economic effects of the seven-month conflict have also unleashed a spike in inflation, the likes of which Italy has not seen since the 1980s. Economists predict an additional 12 million Italians risk slipping below the poverty line because of their inability to absorb any economic shocks, prompting warnings of a social “breakdown” that could rip the societal fabric apart.

Unsurprisingly, the energy crisis took centre stage in the election campaign. While the right-wing coalition has maintained a united front on certain flagship policies, including opposition towards “illegal immigrants” and gay-rights lobbies, cracks have appeared in the proposed handling of the energy crunch.

Meloni has stuck to Draghi’s line: refusing to increase Italy’s record high debt while insisting on capping the price of gas and decoupling it from energy costs. Salvini is of a different view, pushing for 30 billion euros ($29bn) of more debt to help struggling businesses and families.

Whatever the approach, analysts are urging speedy action to tackle the growing social inequality that the coronavirus pandemic had already exacerbated.

“The coming government will have to adopt a strategy to protect the most vulnerable or the situation will become desperate,” said Linda Laura Sabbadini, an Italian statistician whose work has focused on social and gender issues.

What is left?

Polling right behind the Brothers of Italy, at 22 percent, is the Democratic Party (PD). Led by Enrico Letta, the centre-left party has sought to cast the vote as a stark choice between two opposite and irreconcilable visions.

“Either us or Meloni – two profoundly different Italys,” Letta told voters at the start of his election campaign.

The PD has focused its messaging on boosting economic opportunity for young Italians, with a focus on renewable energy, civil liberties and social policies. But the party has failed to strike any partnerships that would help it form a governing coalition, while Letta has been criticised for focusing more on attacking Meloni than promoting his party’s actual policies.

Besides Meloni, Five Star Movement leader Giuseppe Conte has also elbowed himself into the campaign limelight. His politically moribund party polled at 13 percent, positioned as the fourth party this month after a strong campaign in the country’s south.

The south is the area with the highest number of recipients of a “citizens income” scheme – a poverty relief initiative that was the party’s signature policy when it was in power in 2018. Meloni has promised to abolish the scheme, arguing it discourages people from trying to find employment.

Official results are expected on Monday, but it will take weeks before a new government is formed. By mid-October, the two new chambers will elect their respective presidents.

Then, President Sergio Mattarella will start consultations with the two representatives and with party leaders to decide who to appoint as prime minister. The appointed premier will present a list of ministers who will have to be approved by the president and then by parliament in a confidence vote.

Party over?

Pollsters predict a record-high abstention rate on Sunday as many Italians seem unconvinced by the options on offer. But elsewhere – in Brussels above all – interest remains high.

Meloni, who co-founded Brothers of Italy in 2012 out of the ashes of a failed fascist party, had for years delivered high-decibel speeches against the EU and international financial markets, which she portrayed as enemies of Italy’s national interests.

But as the prospect of becoming prime minister nears, at a time when Italy is receiving much-needed EU funds to shore up its underperforming economy, the 45-year-old has softened her tone. She has repeatedly pledged her commitment to the bloc and her support for Ukraine, including by keeping the sanctions imposed on Russia after it invaded its neighbour in February.

Her fieriness, however, at times found its way back on the campaign trail. “The party is over” for the EU, Meloni declared last week during one rally, promising to put Italy’s interests “first”. She also raised concerns after refusing to back a report by the European Parliament condemning the Eurosceptic Hungarian government over rule of law violations.

‘Sceptical voice’ on Russia

Then there are questions looming over her coalition partners’ approach towards Russia.

Salvini, a longtime admirer of Russian President Vladimir Putin, has repeatedly insisted sanctions against Moscow are not effective and should be reconsidered.

Berlusconi, for his part, has struck up a personal friendship with the Russian leader, holidays together included. The 85-year-old said on Thursday that Putin only wanted to replace Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy with a government “made up of decent people”, but he met “unexpected resistance” on the ground.

Andrea Ruggeri, professor of political science and international relations at Oxford University, said Meloni “will not be able to break ranks with the EU on policies such as Ukraine and Russia, but she will maintain a sceptical voice within the EU to appease her electorate”.

“There will be a stronger emphasis on national sovereignty with Italy siding closer to Hungary and Poland,” Ruggeri said.

Preliminary results are expected after polls close at 21:00 GMT on Sunday.