Inside the battle to save Canada’s ancient, old-growth forests

Activists in British Columbia are erecting blockades to try to prevent logging of ancient trees on Indigenous lands.

Vancouver Island, Canada – A colossal battle to save the last temperate rainforest on Vancouver Island, Canada is under way, as police and forest protectors are engaged in a cat-and-mouse chase through hundreds of kilometres of thick woods.

The Rainforest Flying Squad, a volunteer-driven activists’ group, is behind efforts to stop logging companies from extracting old-growth trees in and around the Fairy Creek forest, an area with some of the little remaining old-growth in the province of British Columbia (BC).

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsFirst Nations receive death threats over Canada pipeline battle

Freda Huson: An Indigenous ‘warrior’ for the next generation

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) have arrested more than 150 activists during the past three weeks while enforcing an injunction obtained in March by Teal-Jones Group, one of the main logging companies, to remove the forest defenders.

But that has not deterred hundreds of activists, who have flocked to Canada’s west coast to try to save the forest of gigantic, rare strands of western red cedar and yellow cedar trees, some of which are estimated to be between 800 and 2,000 years old.

“I can tell you that as of Monday all the camps are intact,” said Saul Arbess, a cultural anthropologist from Victoria, BC, who has been involved with the blockades since they began last August. The activists are camped out in various strategic locations that the Rainforest Flying Squad has chosen to block loggers from felling the trees.

Deemed ancient by the BC government if they are older than 250 years, they can tower as high as 25 metres (82 feet) and measure 3.5 metres (12 feet) in diameter. The trees form a cathedral of stunning forest in the coastal, mountainous region that is home to threatened species such as the Western screech owl and a blend of centuries-old firs and hemlocks.

“These trees anchor the entire ecosystem and they’re some of the oldest living things on the planet. And when you cut them down, you are not just destabilising the ecosystem, you’re on the road to ruin,” Arbess told Al Jazeera. “That’s what this struggle is all about.”

Company defends plan

Teal-Jones Group owns Tree Farm License 46, which encompasses the area of the Fairy Creek blockades. The licence spans 3,828 hectares (9459 acres) of old-growth forest; it is one of the last large unlogged watersheds on southern Vancouver Island.

The company, which bought the logging and milling rights from the Province of BC in 2004, stands to profit an estimated $20m from logging 200 hectares (494 acres) of old-growth trees here. Old-growth trees are coveted by industry for their “tight clear wood” – smooth and ideal for products such as shingles and decking.

In an email to Al Jazeera, a representative for Teal-Jones said it holds the right to harvest in the disputed area. “We are a value-added manufacturer. We do not export logs or jobs but mill all timber we cut right here in the province, utilizing 100 per cent of every log,” the statement reads.

“Teal Jones has a decades-long history of engagement with First Nations, responsible forest management, and value-added manufacture in BC. The company plants well in excess of one million new trees every year.”

In a statement to The Canadian Press news agency, Gerrie Kotze, vice president of Teal Cedar’s, a subsidiary of Teal-Jones Group, also said the company’s plans for the area have been “mischaracterised”. Kotze said the company is only planning to harvest “a small area up at the head of the watershed” – about 200 hectares (494 acres) – and that most of the Fairy Creek watershed is unavailable for logging.

But forest defenders as young as 15 are chaining and cementing themselves into the ground and perched high in the trees to block the loggers’ entrance, while other supporters are eager to get arrested for what they believe is a revolutionary cause. “Intact old growth ecosystems make up less than 1 percent (860,000 hectares) of B.C.’s remaining forests,” Greenpeace says.

‘Spiritual holy places’

The area in question sits in the traditional territories of the Pacheedaht and Ditidaht First Nations, who are caught between a colonial, elected governance leadership that has expressed support for the logging – and traditional hereditary leadership that has denounced it.

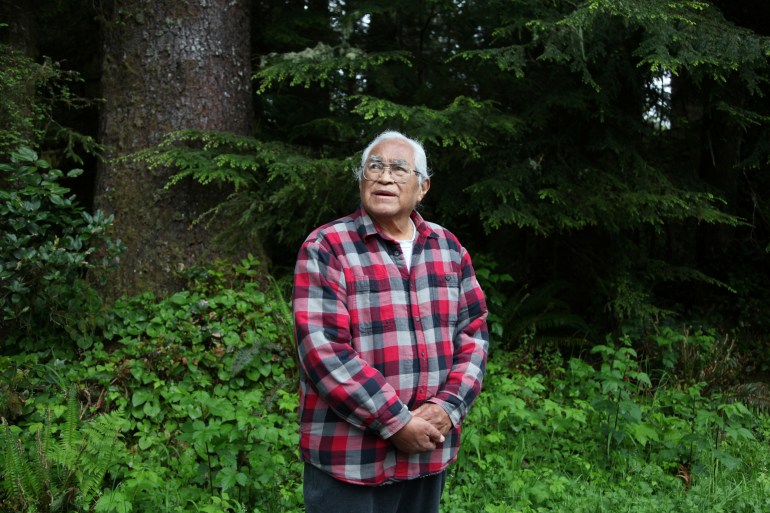

“My grandfather implored to us that the Ferry Lake area, and the two creeks there, were our spiritual holy places,” Pacheedaht Elder Bill Jones, 81, told Al Jazeera. “If the trees are cut down, I think that will be the end of our own hopes of resurrecting our past culture, which in fact, is dead on this reserve – that we will not have any means to address our original, spiritual relationship.”

Jones is a survivor of Canada’s infamous residential schools system, an assimilative tactic the government put in place from the late 1800s until 1996. Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their homes and taken to live in the schools, where they often experienced abuses of every kind.

Last week, Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced it had found mass unmarked graves containing the remains of 215 Indigenous children at Kamloops Indian Residential School, also in BC, sparking global outrage about the mistreatment of Indigenous peoples.

Jones equated his community’s disconnection from their culture and spirituality to residential schools and other colonial violence. He said he is tired of mourning everything that has been lost, and does not want the last of his peoples’ lands to be pillaged.

“I call this entrapment, you know, where they set up a trap, the government. We have no money, we owe money. Even the elected Chief Jeff Jones is locked into contracts with the government and Teal Jones, but we get very little of the profit and don’t have any influence on forest management,” Jones said.

Calls to stop

BC’s forestry industry is a cornerstone of its economy. It provides 100,000 direct and indirect jobs and contributes nearly $13bn to the provincial GDP, according to a 2019 report by the BC Council of Forest Industries.

Premier John Horgan promised to protect old-growth forests during his election campaign last fall, but his government has continued to issue licenses to harvest the trees. It also said its management plans will protect old-growth, but activists have rejected that as insufficient.

Arbess said activists are “asking the government to stop, to make deferrals”.

“And also, we are not opposed as such to logging. We are not opposed to the loggers, to the logging families. There’s a tradition that exists in those families. We want that to continue, but we want that to be in work that is sustainable in terms of the forest,” Arbess said.

A logger working in the area who asked not to be identified for fear of losing his job told Al Jazeera that he identifies as an environmentalist, but is sick of the blockades holding him up from doing his work. He said all the trees should be cut down because they will simply grow back.

“A 2,000-year-old tree is just a tree,” he said.

‘Planet needs forests’

As the struggle continues, three First Nations formally notified the province on June 5 of a request “to defer old-growth logging for two years in the Fairy Creek and the Central Walbran areas”. The Ditidaht, Huu-ay-aht, and Pacheedaht said that would give them time to “prepare their plans” for the areas and comes “in addition to the decision of Huu-ay-aht First Nations to defer logging of its treaty lands”.

In an email, Horgan’s office told Al Jazeera that “these nations are the holders of constitutionally protected Indigenous interests within their traditional territories. It is from this position that the Chiefs have approached us”.

“We further recognize the three Nations will continue to exercise their constitutionally protected Indigenous interests over the protected areas. And we are pleased to enter into respectful discussions with the Nations regarding their request.”

Teal-Jones Group also said it acknowledges that it is operating in the traditional territories of the First Peoples and is working with those Indigenous nations. “We will abide by the declaration issued today, and look forward to engaging with the Pacheedaht, Ditidaht, and Huu-ay-aht First Nations as they develop Integrated Resource Forest Stewardship Plans,” the company’s statement read.

In a June 4 opinion piece in the Vancouver Sun, BC’s minister of forests, lands, natural resource operations and rural development wrote that the province is halting old-growth harvesting licensing. “Pacheedaht, industry tenure holders, and the province have agreed that no harvesting will happen in Fairy Creek while the Pacheedaht develop their own stewardship plan,” Katrine Conroy wrote, adding that the government anticipates more deferrals of old-growth logging to be announced during the summer.

Meanwhile, activists are still flocking to the forest in hopes of saving the ancient trees.

For months, a 69-year-old retired environmental epidemiologist who goes by the code name Bluebird has been making the trek from his home in Victoria with his wife to support the Rainforest Flying Squad.

“The planet needs forests. When you feel the power of an old forest here, the air, it gives you energy walking in there,” Bluebird told Al Jazeera from the main camp run by the activist group. With tears forming in his eyes, he added that the forest is “the best carbon system we’ve ever had”.

“We don’t need to build a fancy carbon storage system, we need to keep forests intact; they suck carbon out and keep it there for thousands of years. We’re clear-cutting them and turning them into carbon emitters. Absolutely, there’s no doubt I’m willing to get arrested.”