Worth a shot? How one-dose COVID jab could help in pandemic fight

A single-dose vaccine made by Johnson & Johnson could be easier to distribute, store and administer than other vaccines.

A vaccine developed by Johnson & Johnson is close to becoming the first single-dose COVID-19 shot to be approved by regulators in the United States, a key first step towards international approval of a jab that could change how vaccines are administered globally.

The drug company filed an application on Thursday to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) after preliminary clinical trial results showed it was 66-percent effective overall and offered 85-percent protection against severe illness 28 days after inoculation.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsPfizer withdraws emergency use bid of its COVID vaccine in India

WHO ‘concerned’ COVID vaccines will not work on new variants

The FDA has scheduled a meeting for February 26 to discuss the data and decide whether to grant emergency use authorisation. The vaccine is also being reviewed by health authorities around the world.

If approved by the US regulator, the company plans to apply for international approvals, something experts say could boost the global vaccination campaign, which has stalled in some regions as manufacturers reported supply chain issues.

What are the advantages of the Johnson & Johnson shot?

The Johnson & Johnson shot’s efficacy rate is lower than the two other vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, which showed 95-percent and 94-percent efficacy respectively.

Unlike the other two vaccines though, it does not require a second dose, which would simplify logistical challenges in the roll-out.

“It’s a very positive development because it is a single dose and can be transported, and stored, in normal temperature so operationally and logistically it is a game-changer,” said the World Health Organization’s chief scientist Soumya Swaminathan.

The vaccine can be kept in regular refrigerators between 2C and 8C (36 F and 46 F) for three months, compared with other vaccines that need to be kept at ultra-cold temperatures. This could aid distribution in rural and remote populations.

“And the higher the number of people we vaccinate, the easier it is to cover the effect of new variants,” Swaminathan added.

Does it work against new variants?

Viruses mutate regularly when they replicate in order to spread and thrive, and the coronavirus has undergone many mutations since it was first discovered in the Chinese city of Wuhan in late 2019.

“When a virus replicates itself, it can make ‘errors’ generating new variants that could spread faster or have a higher mortality rate,” said Zoltan Kis, Research Associate at the Future Vaccine Manufacturing Hub at Imperial College London.

In the worst case scenario, Kis explained, you can have a variant that is so different from the original copy that it requires a new vaccine.

Scientists have identified new variants in the United Kingdom, Brazil and South Africa in recent months which appear to be more transmissible than previous variants of the virus.

The clinical trials of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine that were carried out in the United States, Latin America and South Africa showed an efficacy rate against moderate to severe infection of 72 percent, 66 percent and 57 percent, respectively.

The drop in efficacy in the South Africa trial, which has been seen with other vaccines, is linked to a new strain of the virus, the B.1.351, which appears to be more resistant to the body’s antibody response. Still, the one-shot vaccine offered high protection against severe illness in the South African trial.

How does the vaccine work?

The Johnson & Johnson shot uses a viral vector to carry the coronavirus’s genetic code into the body. This trains the body’s immune system to produce the antibodies against the coronavirus spike protein, so that it knows how to fight it once it encounters the virus for real.

To trigger the same mechanism, vaccines such as Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna advanced mRNA technology, which had not been used in vaccines before the pandemic.

As scientists look to produce new vaccines to combat the new variants, the mRNA technology could have an advantage as it is more adaptable and can be more easily reconfigured to transmit different genetic instructions to the body.

Supply agreements

One Johnson & Johnson shot will cost $10 as the company has pledged to provide the jab on a “not-for-profit basis” throughout the pandemic.

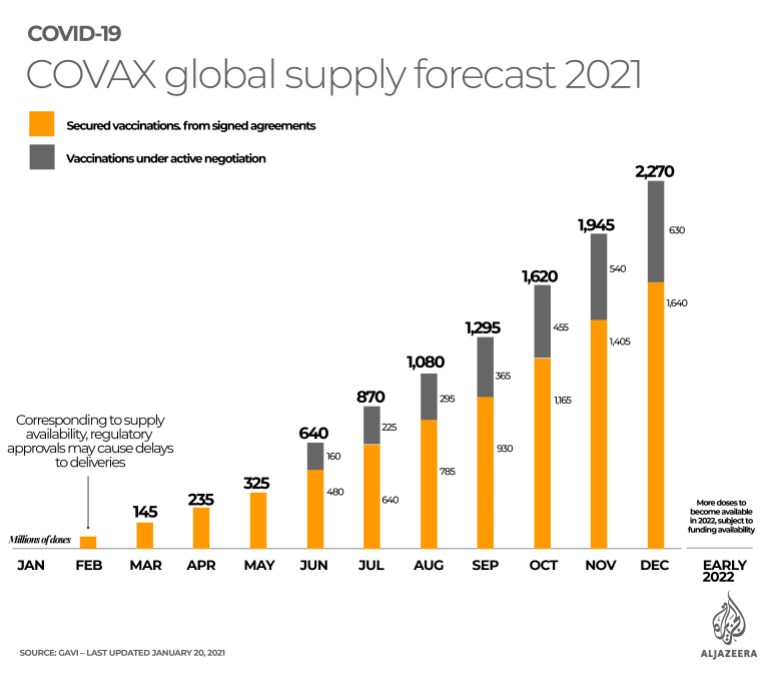

Pending regulatory approval, the company has agreed to provide up to 500 million doses to COVAX, an international partnership that aims to guarantee access to vaccines for lower-income countries, through the end of 2022.

It has also struck agreements to deliver 100 million doses to the US, 30 million to the UK and 200 million to the European Union.

“The challenge now for all manufacturing companies is that they made so many commitments to mainly high-income countries that are now struggling to provide a dose to everybody, including COVAX,” said WHO’s Swaminathan.

The WHO is therefore pushing other countries to let Johnson & Johnson, as well as other major vaccine manufacturing companies, supply COVAX first.

“We would like to see some consideration for equity,” said Swaminathan, noting that countries such as the US and Canada have ordered enough doses of other vaccines to cover their population.

On Thursday, the UN health agency reported that more than three-quarters of global inoculations have taken place in 10 countries that account for almost 60 percent of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP), while 2.5 billion people living in 130 countries are yet to receive a single dose.