‘Hard choices’ for Singapore media after controversial law passed

Concerns about the effect of ‘foreign interference’ law in the country where media already operate under strict regulation.

Singapore – Singapore’s government says its new foreign interference law is needed to prevent outside meddling in the city state’s domestic affairs.

But independent news outlets and observers worry that the broadly-worded Foreign Interference Countermeasures Act (FICA) will further limit freedoms in the tightly-controlled country of 5.5 million people.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsSingapore parliament to debate ‘foreign interference’ law

Can we live with COVID-19? Singapore tries to blaze a path

Singapore becomes world’s most COVID vaccinated country

An opposition member of parliament alluded to FICA as a “Trojan horse” before it was passed into law by an overwhelming majority a week ago.

Representatives from the ruling People’s Action Party, which holds 83 of 93 parliamentary seats, all supported the bill, which the government says is necessary to counter alleged incidents of foreign interference.

Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam said the broad wording of FICA was intentional while stopping short of naming the countries it targets. “The difficulty that we face … in dealing with this foreign interference issue is that out of 10,000 interactions, one might be the sort that we are interested in,” he said.

“And foreign agencies and even non-agencies, NGOs and others, will try and present a legitimate front. So the language has got to be broad enough to cover that – that what is apparently normal, but is actually not normal,” he said in Parliament.

Some people and entities will automatically be classified as “politically significant persons” under FICA, including political parties and members of parliament.

Others can be given this status by the authorities (the Home Affairs ministry says the issue will be handled by an unnamed “competent authority”) and they can challenge it by appealing to the home affairs minister, rather than the courts.

There is no mention of whether the “competent authority” needs to explain the decision – only that it must inform the person or entity that they are considered a “politically significant person”.

The names of the designated will also appear on a public list, according to the ministry.

They will need to report “arrangements” with “foreign principals” and donations of 10,000 Singapore dollars ($7,378) or more, among other rules.

Any individual who allegedly publishes information on behalf of a “foreign principal” and towards a political end can also be fined up to 100,000 Singapore dollars ($73,757) and jailed for 14 years if the affiliation is not declared.

For entities, there is a maximum fine of 1 million Singapore dollars ($737,550).

“There is no clarity on the extent of powers the home minister has under FICA, the intention behind the proposed laws, and how it applies to independent news organisations like us,” said Kumaran Pillai, publisher of The Independent Singapore, a website.

“Whether intentional or not, the government is setting up barriers to entry in the media landscape in Singapore,” he added.

The Independent Singapore, which has 1.6 million unique visitors every month, routinely reports its finances in line with existing licensing requirements that prevent foreign funding. It has 10 staff and relies on advertisements to keep servers humming.

“We do have foreign correspondents working on entertainment, lifestyle, regional and international pieces. If they are filing any local reports, we use them strictly for fact-based reporting,” Pillai told Al Jazeera.

“I have instructed my editors to ensure that there is proper fact-checking and compliance. It is not the job of foreign contributors to add salt and pepper to our articles.”

‘A nuclear bomb’

Independent media outlets in Singapore have long come under fire from the authorities over alleged foreign links.

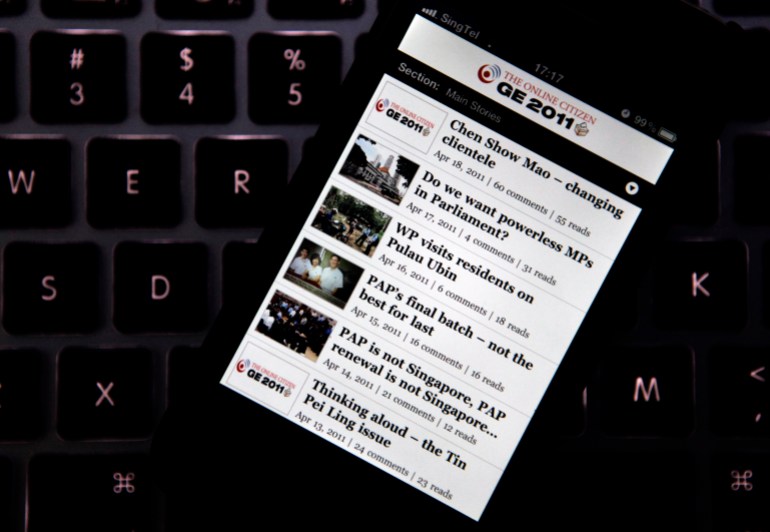

The Online Citizen, a now-defunct sociopolitical website, was accused of employing foreigners to write largely negative articles about Singapore. It was recently shut after authorities said it failed to declare all its funding sources for 2020 when ordered.

New Naratif, meanwhile, an online current affairs website covering Southeast Asia established by three Singaporeans, was prevented from setting up operations in the city-state. The Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA) said the website, which is funded via a membership model and collects subscription fees, “would appear to be funded by a number of foreigners”.

The website had received grant funding from the Open Society Foundations, founded by billionaire financier George Soros.

Last week, during a response in Parliament, Shanmugam said the foundation had a “history of getting involved in the domestic politics of sovereign countries” and singled out New Naratif.

Kirsten Han, who co-founded the site in 2017 and left the organisation last year, said it willingly provided information about the grant and that it “did not come with any expectation or ability to control the editorial decisions that we made”.

New Naratif’s managing director, Thum Ping Tjin, a historian, said the website, which has its headquarters in Malaysia, has 1,221 active members from about 40 countries.

“Singapore is still our biggest country of subscribers, but it is a decreasing majority,” said Thum, who once represented Singapore as a swimmer and is an academic visitor at the University of Oxford’s Hertford College.

He expects to lose more Singapore subscribers if the site is designated a “proscribed online location” under FICA.

“It is a nuclear bomb. The way FICA works is by criminalising virtually everything and then giving the authorities discretion as to whether they prosecute you or not,” Thum said.

“They are trying to close off the Internet, basically, and ensure that there are no alternative and critical voices in Singapore.

“Because at this point, who else is there? There are a few other struggling outlets but they don’t tackle politics the way New Naratif and The Online Citizen do, and quite rightly so, since they want to survive,” he added.

Strict laws

Singapore’s mass media landscape has been a near-duopoly for decades – between Singapore Press Holdings (SPH), which publishes daily national broadsheet The Straits Times, and Mediacorp, which runs the island’s television and radio stations.

While both outlets say they are editorially independent, critics are more sceptical. SPH recently named a former minister as chair of its media business, in a government-led move which was condemned by opposition politicians.

Mediacorp, which grew out of public broadcaster Singapore Broadcasting Corporation, is owned by Temasek Holdings, the state investment fund. Its board includes the permanent secretary of the Home Affairs Ministry and the country’s non-resident ambassador to Kuwait.

Singapore: withdraw the FICA Bill 📢 It contravenes international legal & human rights principles – rights to freedom of expression, association, participation in public affairs, and privacy – and will further curtail civic space, both online and offline. https://t.co/eMe4m1tmKZ

— APHR (@ASEANMP) October 13, 2021

A strict regulatory and licensing environment, coupled with sweeping censorship and defamation laws, have long weighed on freedom of expression in the island nation.

In 2019, the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), which was introduced to tackle “fake news”, took effect allowing Singapore ministers to order that anything deemed an “online falsehood” be taken down or have a “correction” published alongside it.

The orders can be appealed to the courts, but POFMA has already been used against journalists, and activist Jolovan Wham was ordered to post a correction notice on a tweet he shared about Shanmugam’s parliamentary speech on FICA.

Singapore was placed at 160 out of 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index in 2021, which was compiled before FICA was passed.

“Despite the ‘Switzerland of the East’ label often used in government propaganda, the city-state does not fall far short of China when it comes to suppressing media freedom,” the group said.

On Wednesday, in an open letter, Article19 and 10 other rights organisations, including a group of regional lawmakers, called on Singapore to withdraw the legislation, saying it breached international legal and human rights principles.

“Almost any form of expression and association relating to politics, social justice or other matters of public interest in Singapore maybe ensnarled within the ambit of the legislation – making it difficult in turn, for the average individual to reasonably predict with precision what conduct may fall foul of the law,” the organisations wrote.

No known cases

Analysts say the media environment that emerges as a result of FICA could have a damaging effect even on SPH and Mediacorp.

“It seems like in the government’s view, the ideal media is that you have SPH and Mediacorp, and they are both heavily read and trusted by Singaporeans,” said Ang Peng Hwa, a professor at the Nanyang Technological University’s Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information.

“But that’s not how the news media ecosystem works anywhere in the world. You need a diversity of media, you need your oppositional and independent media sources,” he added.

“And so FICA looks to have the possibility of suppressing independent journalism as well as oppositional journalism. It is hard to see now, but in the long run, [the lack of competition] will hurt both SPH and Mediacorp.”

The ministry has stoutly defended the need for FICA and in a letter to the Straits Times just before it was passed stressed it would “not apply to Singaporeans discussing issues or advocating any matter”.

There have been no known cases of Singapore journalists being involved in full-blown influence campaigns.

In the academic sphere, the country expelled Chinese-born American academic Huang Jing in 2017 for being an “agent of influence of a foreign country”.

“He knowingly interacted with intelligence organisations and agents of the foreign country, and cooperated with them to influence the Singapore government’s foreign policy and public opinion in Singapore,” the Home Affairs Ministry said.

Although FICA does not specifically target journalists, it can be used if their ventures are found to be part of hostile information campaigns, said Eugene Tan, an associate law professor at Singapore Management University.

“It’s not a question of whether but when FICA will be applied in such circumstances,” Tan said.

Tan, a veteran political commentator, does not believe the law will curtail independent journalism in the country. “I appreciate that it is a legitimate concern but only if FICA is misused by the authorities.

“It is crucial to recognise that there must be grounds for the law to be applied in the first place. So long as journalism is independent, that is it accurately represents the journalist’s reporting and viewpoints, and not done at the behest of a foreign proxy, FICA cannot be used.”

For Pillai, the reaches of the law are personal, as an independent publisher and executive committee member of the opposition Progress Singapore Party, which does not hold any parliamentary seats.

Pillai says he is currently allowed to “participate in party politics and get involved in any business without encumbrances”.

“I am not sure how the new laws will impact my current working relationship in the various organisations that I am involved in today,” he told Al Jazeera. “Personally, I might have to make some hard choices in the future.”