US renters live under eviction threat despite gov’t ‘protections’

Housing advocates, renters say eviction notices are still going out despite coronavirus lockdowns and some moratoriums.

Atlanta, Georgia – Not long before the novel coronavirus shuttered bars and restaurants across the country, Michael Aaglan, 51, was excited for a new start. But just a few weeks into his training at an Atlanta, Georgia bar and steakhouse, management called with devastating news: The bar would be closing indefinitely due to COVID-19.

About a month and a half later, Aaglan is still waiting on unemployment. Without that money, he could not pay April’s rent and doubts he can make May’s.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsCoronavirus prison cases raise alarms, calls for inmate release

Arkansas activists sue to gain release of state prisoners

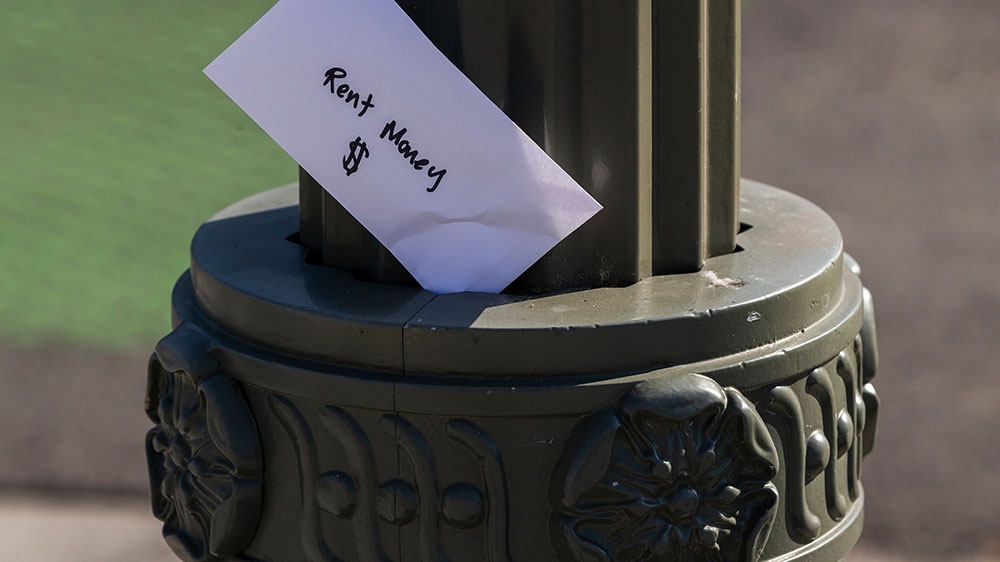

On April 8, the company managing the property where Aaglan lives sent him a letter demanding he pay or vacate within three days. A panicked Aaglan emailed and called his property manager to work out a payment plan. On top of not having money for rent, without unemployment, Aaglan has had to rely on his management at the bar for help with food. He struggles with the loss of control. Between calls to his complex’s management and the United States Department of Labor, Aaglan said: “Mostly, I find myself vacillating between eating nothing or devouring everything in sight, getting no sleep or doing nothing but sleep.” He has yet to receive dispossessory paperwork – or a notice of eviction proceedings. While Aaglan waits for unemployment, the threat of filing is always there.

As the US enters a period of unprecedented joblessness, more than a dozen cities and some states have enacted some kind of eviction moratorium. The federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) act prohibits evictions until July 2020 if the owner has a federally backed mortgage, which accounts for about one in four rental units, according to research by the Urban Institute.

In Atlanta, despite the unemployment rate and the statewide shelter-in-place orders that expire on Thursday, apartment complexes and landlords are sending out warnings to pay and threatening to evict. Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms called for an eviction moratorium on March 17, but filings have continued and advocates worry there is no clear oversight mechanism to stop illegal filings.

Jane Hansen, a public information officer for the Supreme Court of Georgia, said that although eviction processes can be filed online, the courts are not acting on them while the state’s emergency judicial order keeps courts closed to all but essential functions. Hansen said deadlines for tenants to respond will be pushed back until whenever the emergency order, recently extended until May 13, expires: “If you had 30 days, you’ll have 30 days once [the emergency order] is lifted.”

Hansen also said “if people are going around the courts, that’s not within our authority” in regard to evictions continuing in Georgia.

Like Aaglan, a number of workers who lost their jobs as a result of the coronavirus pandemic said they were unable to pay rent while waiting on unemployment benefits. Carlos Soto and his sister were both laid off in March, and neither received unemployment benefits by the time April’s rent was due. After they were unable to pay, the management company of the apartment complex left a notice from the collection department on their front door. The note asked for the full rent: $1,200.

Soto also went to the management company.

“We have a good relationship. [We pay] everything on time,” he told Al Jazeera. They gave him two options: pay half right away and the rest at the end of the month, or pay half and split the other half of the rent into multiple payments. They would waive the late fee. Soto considered the extension, “a little help[ful]. But, at the end of the day, we still have to pay everything.”

Threats and notices

Natalie McLaughlin is an organiser with the Housing Justice League of Atlanta. During the coronavirus pandemic, the organisation set up a hotline that McLaughlin said can receive and conduct intake for over 200 calls a day. The Housing Justice League tries to act as a lifeline to renters like Aaglan and Soto, providing them with eviction defence materials. McLaughlin said the group is seeing landlords threaten tenants with eviction and asking them to sign repayment plans with hefty interest rates.

Certain businesses, including restaurants, gyms and salons, began reopening in Georgia with restrictions last week. The reopenings have thrown into question whether furloughed workers will still be eligible for unemployment benefits, the only money workers like Soto have to pay their rent. Georgia Labor Commissioner Mark Butler said those who do not feel safe going back to work can refuse to return and still get benefits, but they must show proof that their workplace is unsafe. Butler did not elaborate on what proof would be accepted. The state has also said employees who are working reduced hours may still qualify for partial benefits.

Georgia courts are closed until mid-May due to a statewide judicial emergency order. Landlords can still begin the eviction process by filing online for a dispossessory proceeding, however. Normally, the local sheriff or a private process server would then deliver the dispossessory. According to attorney Jennifer Feathers, sheriffs may not be serving dispossessory papers, but private process servers certainly are.

Feathers, a lawyer in the Atlanta metro area who regularly works on eviction proceedings, feared for her friends in the hospitality and entertainment industries after the coronavirus shut down most businesses. She shared a post online offering to help unemployed service workers being threatened with evictions. She got email after email and said she had to solicit law school friends to respond to the 1,500 renters worried about their housing.

Feathers has worked on more than 300 cases this month alone -cases where she said renters were served with the dispossessory paperwork. A dispossessory went out to a private server in Fulton County as recently as April 29, according to Feathers.

“If it comes down to feeding your family or paying your rent, feed your family,” Feathers said. “It will affect your credit, but the sheriff is not going to come and throw their furniture out.”

So-called “put-outs” where a sheriff will physically move renters’ possessions out of their homes are not happening during the virus-related shutdowns. No put-outs buy renters more time, but this does not mean magistrate courts are not processing evictions.

Feathers also said a number of the renters she talked to were facing harassment from landlords rather than the formal eviction process. According to Feathers, landlords are “sending threats saying, ‘We’re going to put you out if you don’t have this money.’ They’re trying to bully people.” In addition to threats of eviction, Feathers said, landlords are not performing maintenance using the coronavirus shutdowns as an excuse.

Affordable housing crisis

The willingness of landlords to begin the eviction process and send threats during the coronavirus pandemic indicates a looming housing crisis.

Brian Goldstone is an anthropologist working on a book about homelessness and evictions. He echoed Feathers’s warnings that “If your landlord is filing for an eviction today, the sheriff isn’t going to show up today. You’ll go to court at some later date in May or June. But that is going to happen eventually.”

There is another, informal level to evictions, according to Goldstone, where landlords pressure tenants who can’t pay to leave without filing anything.

“What I’m finding is that informal evictions are still very much happening,” Goldstone said. “We’re going to see an explosion of homelessness by June or July.”

A little more than 91 percent of renters ultimately paid at least some rent by April 26, according to the National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC).

NMHC President Doug Bibby said that while the number of renters trying to pay their bills was “encouraging”, renters’ “financial security is unclear”. Bibby urged the federal government to enact a renter assistance programme.

According to Senior Policy Analyst Laura Harker at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, housing issues go far beyond evictions. Harker acknowledged moratoriums on evictions were important first steps. In an email to Al Jazeera, Harker wrote, “Aside from high housing costs, conditions such as overcrowding, a lack of kitchen facilities, poor water quality, a lack of broadband access or a lack of plumbing facilities also contribute to housing problems [in Georgia].” She pointed out that Southwest Georgia is a site of both “severe housing problems” and high rates of coronavirus infections.

Aaglan, meanwhile, tries to keep upbeat despite his worries over rent and unemployment. But he is finding it difficult.

“I’m healthy and have food, but the feeling that I’m sinking in slow motion, [that I’m] in quicksand, is palpable,” he concluded.